This week we’re doing something a little different. I had the pleasure of interviewing Jordan Schneider, publisher of the ChinaTalk Substack and senior fellow at the Center for a New American Security. Our conversation provided deep insights into the evolving dynamics of global technology and geopolitics as they relate to China, US-China relations, and AI development in China.

We discussed China's role in global technology and its ongoing competition with the United States. We debated the fairness of U.S. actions like banning TikTok and imposing tariffs on Chinese goods. We also talked about AI regulation in China and the potential for regional conflict.

I hope you find this discussion as enlightening as I did. If you have any questions or would like to see more interviews like this, please leave a comment what you’d like to see next!

Topics and Timestamps

0:37 - How did you become interested in China?

1:22 - U.S. and China competition over the decades

6:37 - Is it fair that the U.S. is banning TikTok, electric vehicles, and various other goods? Does fairness matter?

11:02 - Is China the technological competitor the West thinks it is?

23:20 - The question Jordan didn’t want James to ask

26:58 - AI regulation in China

34:19 - How has working at tech companies in China changed over the years?

36:37 - Will things get better between U.S. and China?

You can read the transcript below or listen to our conversation above (edited for clarity).

Introduction

James Wang - All right, we have Jordan Schneider, publisher and host of the popular ChinaTalk Substack and podcast.

He’s a fellow at the Center for a New American Security, fellow former Bridgewater guy, and also a former corporate minion in a Beijing tech company, as far as I know.

Jordan Schneider - Indeed.

James Wang - Yeah, so, hey Jordan.

Jordan Schneider - Great to get to hang, James.

How did you become interested in China?

James Wang - Yeah, great to have you here too.

It's sort of turnabout's fair play in terms of the previous podcast.

So yeah, I mean, just in terms of listeners on our side here, I just wanted to ask first, since you have this popular substack, podcast, etc, how did you get so interested in China in the first place?

Jordan Schneider - I kind of moved there and then got interested, which is like, I guess an odd sequence. I wasn't super into my job, applied for various fellowships around the world, got a free ride to Peking University, and then when I landed, my mind was kind of blown. There’s something kind of intoxicating about an entirely new language and hemisphere that really got me going. It’s been over seven years now on this journey of 24/7 trying to understand China, which has just been a lot of fun.

U.S. and China competition over the decades

James Wang - It's been an interesting time, especially post COVID, but also during the entire decade. And more recently, we had the big announcement of tariffs come out from the White House.

I'm not going to ask in depth — I think you have a great article and great interview there that people should listen to — But I'm going to give a little bit of a layup here, just because I think most of the audience on my side here are finance and tech people.

Do you think, with the tariffs and everything, that the U.S. is in competition with China?

Jordan Schneider - Yeah, whether America likes it or not, it's sort of a truth like pretty close to universally acknowledged.

I mean, you have to define the scale and scope of competition. And there are lots of different dimensions where maybe the two countries, political systems, firms are competing, aren't, should be competing, aren't.

But actually, let's wind the clock back to 1973. You have Nixon goes to China, re-establishes relations with Beijing after the two countries basically didn't talk to each other once Mao won, and the hope back then was that China would be this political counterweight to the Soviet Union. That turns out pretty well.

And then once the Cold War ends, the sort of next hope was that China would, you know, as it continued to engage and grow and trade and increasingly trade with the world, it would bend towards a more liberal and open direction. I think a lot of people were very optimistic and hopeful about that through the 80s, even past Tiananmen into the 90s and 2000s.

But once we hit Xi, and particularly Xi, I'd say like 2016/2017, it became very clear that a lot of the assumptions that folks in the US and the West more broadly had about what increasing economic development would do to the Chinese political system were unfounded and that it was much more likely to expect a China that was trending in a more closed and autocratic direction than a more liberal and open one, kind of regardless of whether or not the U.S. was doing all it could to help China kind of grow from a technological and economic perspective.

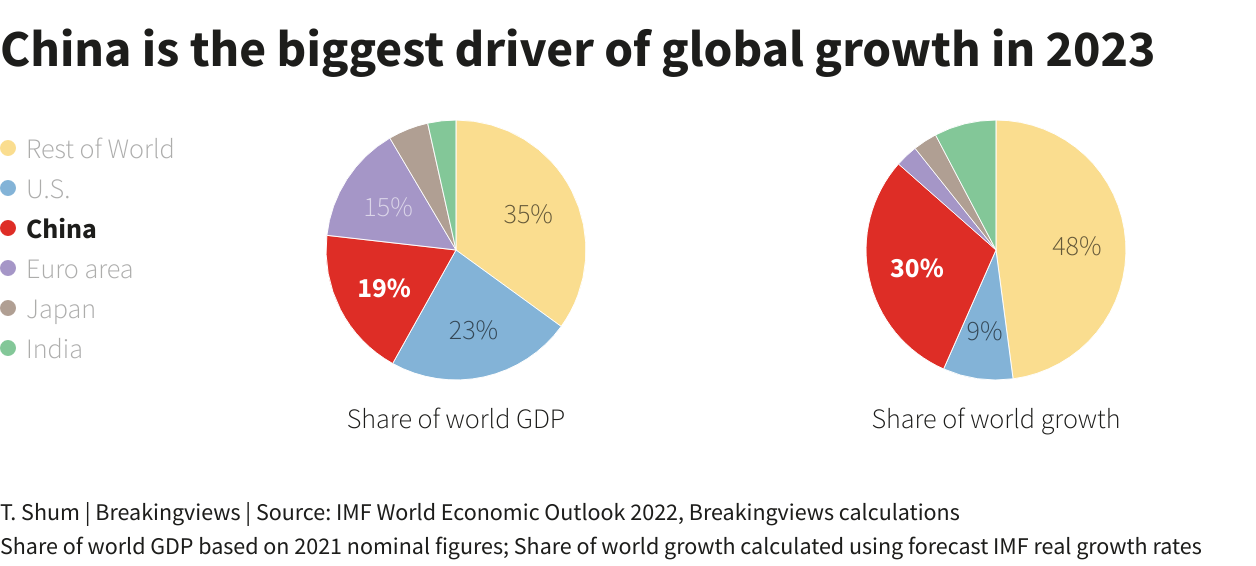

So why does it matter for the U.S. and G7 and other countries around the globe that China is on a different trajectory? I think it's not just issues around domestic governance with stuff that makes folks really uncomfortable with regards to Xinjiang and Hong Kong, but also China's role in the world and as an increasingly large percentage of the global economy, with more and more of the technological commanding heights of the 21st century under the broader wing of Beijing.

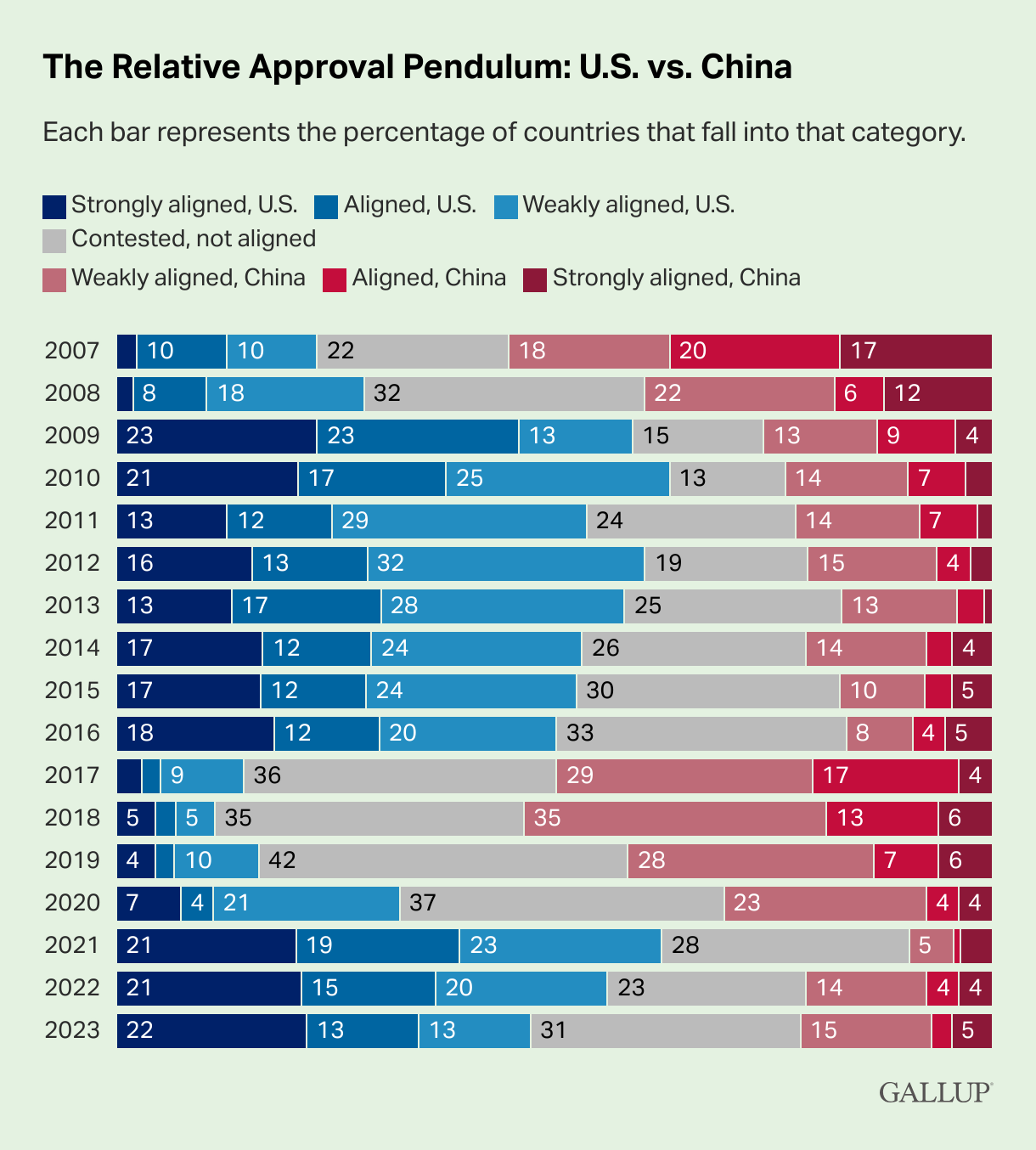

The question, I think, is whether the liberal world is comfortable with a sort of more technologically and economically powerful China, which has a different view of how the 21st century would play out relative to how it relates to its neighbors and how the world would be organized more broadly. And downstream of that, we've had a pretty strong consensus, at least in the U.S. political class — and I think it's fair to say in polling numbers — both in the U.S. and around the world, that we would rather see a 21st century in which China is not necessarily calling all the shots.

Is U.S. and China in competition? I think, from a military capability is one [way they are in competition] — this has clearly been the focus of the US over the past five to seven years or so. On a technology competition perspective, we've seen stuff like the TikTok ban and export controls on GPUs and semiconductor manufacturing equipment. We've seen the rollout of the Inflation Reduction Act and this Chips and Science Act meant to boost domestic production of strategic industries, all partially in response to this latent worry that a world state in which these actions don't happen lead to one where China continues to have increasing technological, economic, diplomatic and military leverage over the U.S. in front.

So whether we like it or not, it seems pretty baked in for the foreseeable future that there will be different kind of levels and strands of competition between China and the U.S. and its allies.

James Wang - Right. And I think that is helpful context for folks and makes a lot of sense.

Is it fair that the U.S. is banning TikTok, electric vehicles, and various other goods? Does fairness matter?

James Wang - Is it fair that the US is banning TikTok and basically banning EVs and whatnot?

I mean, I have an answer to that in terms of this — probably fair, given that it's banned in China, given that U.S. stuff is.

Jordan Schneider - No, that's a really interesting question. I mean who is it fair for? The American consumer that doesn't get TikTok filters? Doesn't get to save $15,000 on a car? Yeah, I mean, it kind of sucks on the margin.

Is it fair for the Chinese private sector entrepreneurs? Is it fair for Zhang Yiming, the CEO of TikTok, posting on Weibo about how he wanted China to be more liberal and open? No, I don't think so. It really sucks.

Does the sort of Chinese political apparatus have it coming? I think absolutely.

You just mentioned, James, Google and Facebook have been pushed out for years now, and there's been a very long and aggressive effort on the part of the Chinese government to sort of stimulate domestic demand and prop up domestic competitors to the likes of Tesla and whatnot. So, I mean, I think it’s not surprising. I also think fair doesn't have a lot to do with it anymore.

Given that this is sort of a national strategic competition at this point, countries are going to try to make sure that their own industries are protected and that particularly ones that have like long term economic, technological and strategic importance like the information space broadly defined or, you know, cars, which is just like a big part of the global economy.

It strikes me as overdetermined that once we establish the predicate that the U.S. and China are in competition, that a lot of industries will end up getting bifurcated to one degree or another.

And information and news as well as cars seem to me like two pretty obvious candidates for being ones where governments on both sides end up taking more aggressive action.

James Wang - I'm glad you took it that direction because that definitely went a little bit differently than I thought.

It definitely makes sense from a national competition, nation states, and political class. But from the perspective of global public opinion, there's been a concerted campaign, certainly from the Chinese side, for an audience in, say, the Middle East and Southeast Asia and other places, saying that whose fault it is matters because it's a moral argument as to who disrupted the status quo first. And a lot of these arguments are that the U.S. has been the one that's been the aggressor in this.

Jordan Schneider - I think tariffs on EVs and, you know, banning TikTok is like small ball when it comes to global public opinion. And what's probably more relevant to look at is the polling numbers of approval for China's role in the world in the world versus America's role in the world over the past 10 years, which have swung in a lot of countries as much as like 30 points against China basically due to how Xi has decided to position China on the world stage.

Without that changing—which I think it's hard to find anyone making a compelling argument that that sort of thing is likely in the near-to-medium term—then the sort of stuff around the margins of U.S. trade policy doesn't necessarily seem like the sort of thing that's really going to resonate with anyone besides the investors that James is hanging out with who are a little annoyed that they got to put factories here instead of there.

James Wang - Yeah, totally. I mean, I hang out with various government people too, and some of them definitely do have strong opinions, but ones that swing quite quickly. The Philippines, for example, sort of turned on their heel quite quickly, even within a single administration in terms of their opinions of China.

But one of the things that I hear a lot from casual commentators, it's essentially China can do anything, right? Like look at what China's done already, look at how far they've come. They've basically gone from rural backwater to industrial superpower.

Is China the technological competitor the West thinks it is?

James Wang - Given that they are able to do all this stuff, what do we think is the state of their current push for leadership within AI, within semiconductors, within all these areas that have become huge, global, competitive landscapes, area of industrial policy, and just really hot in terms of all the different investments and activity around it?

Jordan Schneider - I'd be curious for your answer on this, James, but like, at the end of the day, China is a developing country, like GDP per capita is like $12,000 or something Google tells me, with hundreds of millions of people who are still [making] $1-5 a day.

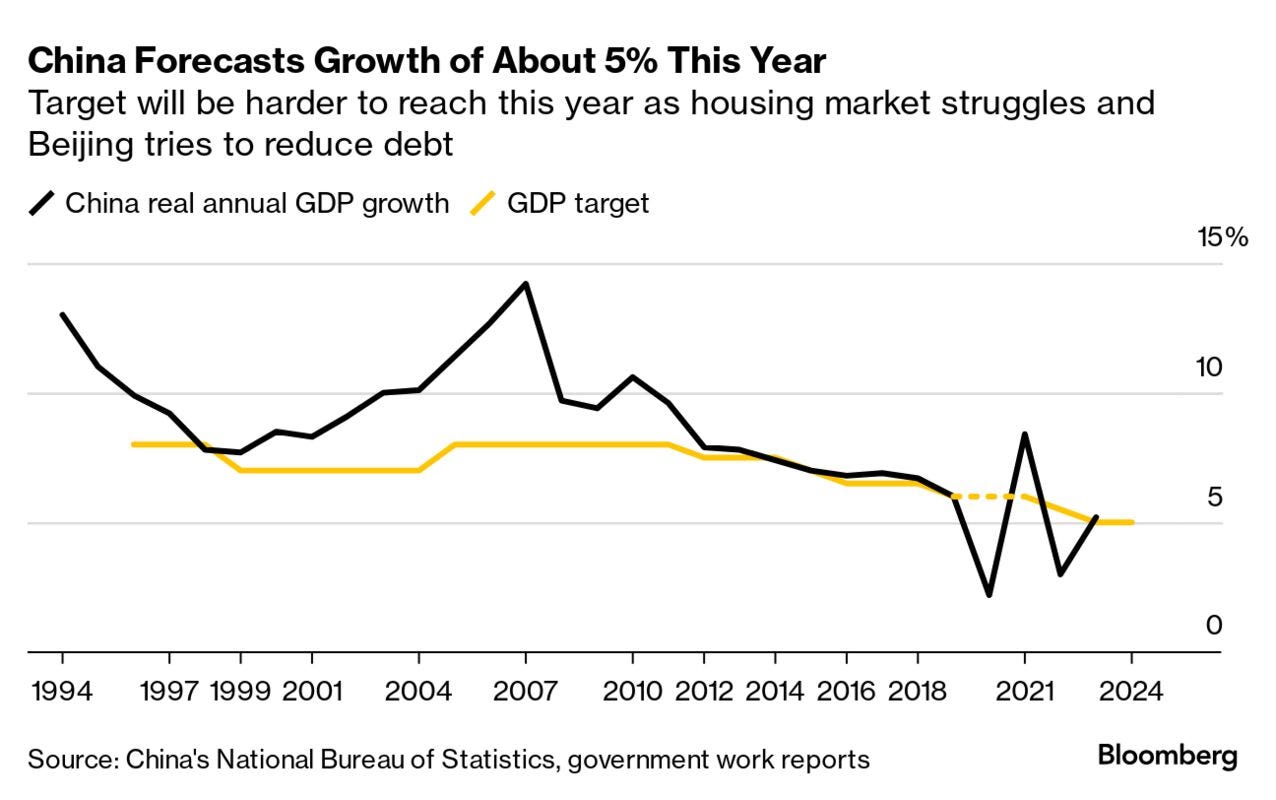

If you look at the broad scope of the Chinese economy, a lot of the growth has come from investment as opposed to productivity growth.

It’s pretty concerning and a bit of a human tragedy that we're seeing China slow down from the 7-10% [growth] to — they said 5% last quarter — but most people think it's back down to the 0-3% range. That's a bummer because there are still a lot of poor people who deserve better lives and better health care and education in China. But I think it's also important to recognize that the country can't do everything all the time. And there are still a lot of internal social, demographic, economic, technological challenges that China is really going to need to figure out in order to break into the “Developed Country Club”.

If you have a GDP per capita of $10,000 with such a huge country, you can still do a lot with that, swing your weight around, and build up some really competitive industries.

I feel like there's been a bit of a reckoning and reset on future expectations of what Chinese firms can do. And there may be outliers and there could be spikiness around AI algorithmic development or leading-edge hardware or what have you. But zooming out, I think there's just a lot of broader challenges that the Chinese government and economy are going to have to figure out.

James Wang - Yeah, I agree.

And it is funny that everyone likes to talk about China, just being able to just throw their weight against something and basically do anything. I mean, anytime you take any sort of extreme, it usually is wrong. That’s usually a useful heuristic.

And just because they're able to, with—like you said—investment, a lot of FDI (Foreign Direct Investment), just throw people initially at manufacturing with cheap labor that's relatively well-educated and good roads that they eventually built around… That doesn't mean you can necessarily get global leadership without help and without anyone else to build upon in semiconductors or AI where it is a global ecosystem with everyone pushing the things forward. China trying to do it alone and being able to do it alone is probably a different kind of ballgame. It's just like, again, another extreme.

If you look at the broad scope of the Chinese economy, a lot of the growth has come from investment as opposed to productivity growth.

Everyone always said how crappy the stuff out of the Soviet Union was. But actually you had really talented physicists, pretty good machining, and whatnot. It’s why you had a pretty good Soviet old-style military for so long. And I collect some Soviet watches — they're actually pretty good if you look at them — but that didn't mean that they were able to build a world-leading semiconductor industry. It didn't mean that they were able to catch up in terms of technological leadership of the new age.

And personally, I think the same thing for China. I've been on the hobby horse of NVIDIA having a huge moat, but the global research AI community has leadership pole position beyond any individual firm. But I asked that question in part because it is something that comes up a lot.

And, similarly, the conversations that I've had casually within US tech: China's sort of a mysterious place, right? They assume that they’re able to put everything, all of its resources, and a huge number of people against anything. And given that, it seems like you should be able to accomplish almost anything.

Jordan Schneider - The proof is sort of in the pudding. I think if you look at the top five market caps of the biggest Chinese tech firms and you look at the top five market caps of the American tech firms, it's like one adds up to like seven trillion and the other adds up to like six hundred billion. So clearly there are some structural advantages that Chinese firms face, particularly on the manufacturing side.

But fundamentally, I think American firms really have done a better job — first, they have a richer domestic economy to work with, and then they're able to expand across the world in the way that Chinese firms have really struggled to over the past 20 years.

And whether Chinese firms will continue to, or whether they won't be able to because of geopolitical [reasons] — because Beijing has screwed up diplomatically so much — and [others are] not comfortable buying stuff from Chinese companies, then the hands will be forced.

But look, at the end of the day, I think that's like probably the most relevant tale of the tape here. How big these companies are and how much money they make is how you should extrapolate, as opposed to anecdotes or a guess as to latent potential based on reading a handful of FT articles. That seems like the right way to level set yourself.

James Wang - And there's also a fundamental difference between certain industries you can make work well with command-and-control type economies and certain industries you can't, right?

I recently had spoken at a National Academies Workshop on biosecurity and some of the folks within high performance computing there were saying, “You know, China tops the super computer charts basically every year, along with the number of publications. No one ever cites those publications, and also no one ever uses those computers either, because they're basically purely built to top the benchmarks and are not really usable in any real way for any real workloads.”

So there’s a difference in a free market — a lot of different kinds of competition versus a government fiat saying, “This is the important thing,” but not necessarily having the people who are motivated and going after it.

Jordan Schneider - Yeah, I mean, when it works, it's really dramatic, right? Like solar and electric vehicles are the two that people point to. But we don't notice all the times it doesn't work. And the times it doesn't work aren't just wasting money, but also there's an opportunity cost of capital and talent that gets spent in ways that are just less impactful or efficient.

Mao obviously was way on one side of the spectrum. And then you had Deng in the reform era, which loosened up a little bit and knew that they were so far from being a globally relevant strategic player that they kind of let the market do, by and large, what it wanted to do for a while.

And I think Xi saw two things happening. First, slowing growth and demographic challenges on the horizon. And second, he could almost taste it and figure that if we just pushed our entrepreneurial energy and state capital a little more in the direction of the industries that we think are strategic, then that'll be our way of really playing in the big leagues. And sometimes it works and sometimes it doesn't.

It seems to me that, over the long term, having this be a supplement rather than a core of your economic strategy will play out better for you over a decadal horizon than really trying to have this be something that's run out of government offices, as opposed to more market forces.

James Wang - It is crazy just thinking that there is still pretty extreme poverty in certain parts of China, especially the rural areas / the places away from the coast, because you do have a pretty big bifurcation. You have a lot of millionaires and billionaires in China at the same time as you still have poor rural areas. Like, you [do] have some of the different tier cities popping up around, but it's not the glitz and glam of Shanghai in terms of all of those different cities and areas.

And a lot of the economy did get driven from market-driven domestic consumption back into this investment command-and-control, and notion that, “We know what's the most important stuff that we need on horizon.”

Jordan Schneider - I mean, this is the real tragedy of Xi, right? He has this vision of making China great again and the Chinese dream, and it is one predicated on geo-strategic power. But there is a strain of him that also clearly cares about poor people, and part of his big effort was to end poverty in China. The problem is that the part of his personality around global competition has risen to the fore.

There's a way in which a CCP leader could have defined national greatness by increasing domestic consumption and improving health care and education and living standards for everyone, which would have de-emphasized these money sinks that sometimes pay out, but oftentimes don't for the Chinese people at large. But instead, we're left with this one, which leads to a backlash from the rest of the world being more wary of China, which is something that ends up slowing Chinese economic growth, and screwing those poor people. Those poor people would have had better long-term economic outcomes if the Chinese economy was able to grow more because it could be more cleanly integrated with the global economy.

James Wang - Totally. I mean, hey, just look at Australia, right? Australia really should be China's absolute best friend ever. And it was kind of going that way for a little bit. And now they're buying nuclear subs from the U.S.

Jordan Schneider - Yeah. And you know, the fact that you have to spend money on this stuff is like, what's the point?

[Xi] has this vision of making China great again and the Chinese dream.

The question Jordan didn’t want James to ask

James Wang - So, pivoting from that — and feel free not to say if you feel it's too speculative — but what do you think the probability of a hot conflict breaking out within the region is?

Jordan Schneider - Man, I was trying to think, what could you possibly say that I would not give you a probability on?

Well, we have to define hot conflict, right?

I set up a poll on Manifold of what are the chances of one service member dying from PRC/Taiwan, US, Vietnam, Philippines, in a China-related incident over the next year. I think that's at like 20% right now? But that's different than like a dramatic, horrific shooting war. And for that scenario over the next three years, I put it at like, I don't know, 1% or something. Over a 15 year horizon, like maybe up to 3%? I'm not super stressed out.

The thing that does sort of worry me is this succession dynamic. One will recall the only other time the PRC started a war was in 1978 as Deng (Xiaoping) was trying to consolidate control and he used the PLA and his ability to basically bully everyone else in the system who did not want to go and fight Ho Chi Minh—of all people—into starting that war, [as] being part of his way to assume power after Hua Guofeng. Things get weird when leaders get old and die.

And, particularly, we had a pseudo succession system that the CCP tried to set up after the death of Mao that has now been blown up.

Xi’s got to do something about this at some point, but I think there's been a really awkward and messy history of the CCP trying to set up successions. You had Lin Biao where things didn't end up working out for him. He flies off in a plane and crashes in the middle of Mongolia. You have the sort of mess I think you can even say was Xi’s succession to power and, you know, him disappearing for a few days and like Bo Xilai ended up going in jail [as well as] Zhou Yongkang.

Things get weird when leaders get old and die.

I think the Chinese domestic, high-political dynamic spilling over into something international is the biggest wild card for me over the next 10 years. I think that’s the type of thing which is far more likely to trigger something than a premeditated risk-benefit calculus happening, or Taiwan declaring independence and China deciding that's unacceptable. So I don't go to sleep at night stressing out about it. But that's the scenario that I think people should do a lot more hard thinking on.

But unfortunately, that's also the one we can do the least about. Whether or not Taiwan has more of a credible defense I don't think is going to matter. If that's like 10 or 20 percent better, I don't think that's going to matter to the enterprising person on the Politburo who's using the PLA to edge out their their rival as they try to figure out what happens after Xi.

AI regulation in China

James Wang - All right, in terms of state of AI regulation and what kind of impact that's been having in China, what sort of thoughts do you have on it?

Jordan Schneider - I mean, I think it's like low-to-moderate. There was this concern early on that the LLMs are untamed and they'll say controversial, political things that the Chinese regulators will never allow.

Look, like, ChatGPT is no longer racist. It's pretty hard to get [the Chinese models I’ve tried] to say obnoxious stuff. I think the regulators have sort of revised their initial proposals, and now it's like you need to be 95% not anti-party or whatever, which is reasonable and a bar that they've been comfortable with. Like you've had dozens of models be approved for public use over the past year or so. So I don't necessarily see like regulation as being something that's really going to define the future of AI in China or the US.

James Wang - For a while — and we talked about this a little bit when I was on your podcast — commentators were actually saying China will be the global AI superpower because of the amount of data and lack of data privacy that they have. I think fewer people are saying that these days, but I'm just curious from your perspective, do you see a particular advantage that China has?

Is there something that might help bring them from behind currently? Some sort of superpower they have that maybe the West or the U.S. or other folks don't have?

Jordan Schneider - Yeah, I mean, data is a lie, right? We're doing synthetic data nowadays — like who the hell cares how many users you have on your platform?

In terms of structural advantages or disadvantages, you’ve got three components, right? You got algorithms, you got data, and you have compute.

I think compute is the one [that is] the clearest to project out into the future. Like, China's not gonna get NVIDIA stuff, and that is gonna suck a lot more in 2026 and 2027 than it sucks now.

To what extent is that gonna matter? Are these algorithms gonna get so efficient that you don't need the latest and greatest stuff? Can you just steal training runs? Can you just steal model weights and then deploy tiny efficient models and basically get what you need to do? Maybe, but that seems to me to be sort of projecting out the easiest thing. The future of Chinese compute is going to be pretty dramatically different from what the rest of the world is going to be able to access.

In terms of data, I mean, who knows? I just translated this roundtable of the Head of ByteDance Research and a number of prominent folks in the China world. None of them were stressed out about data, which is kind of remarkable. I think initially people were like, oh, there's not enough data in Chinese out there, which is ridiculous because you can just train on English data, say translate, and your model can soak it up and be able to function.

I mean, the one interesting argument is from a manufacturing perspective, right? Like if you have more factories and more cameras in your factories, then maybe you can train better models for specific industrial uses. But I think what Google and OpenAI have been showing recently is it's just going to be one model to rule them all, more likely than not, at least into the sort of relatively near future. So I don't know if that's a huge edge that China necessarily has.

And then on algorithms, it just comes down to brain power and talent, right? And you're seeing really interesting state-of-the-art stuff that's developing in novel directions from the West with places like DeepSeek. But we are also in this new paradigm where the capabilities that Anthropic vs. Google vs. OpenAI have are different in their models because Google found out some secret sauce to do two million tokens and OpenAI has got Sora, which no one's come close to matching, which is clearly some domestic, internal innovation. Now, is that the sort of thing that ends up leaking out of these labs because people talk [and] folks get hired in and out from the US to the Chinese ecosystem? Maybe, maybe not.

I think there are a lot of unknowns there, but, insofar as compute is going to be a structural constraint over the next 10 years, when it comes to the rollout of AI, it seems like a pretty big advantage to be able to lean on all the incredible stuff that NVIDIA has in their pipeline vs. hoping that with, you know, ersatz tools and whatever that Huawei can end up making competitive chips and systems.

James Wang - Thinking about that, it is a real shame for the Chinese tech ecosystem that they don't have as much exchange now with U.S. companies. I mean, Baidu originally had their big research lab in Silicon Valley. If all of the big Chinese tech firms had that, “We're willing to pay for a lot of these AI researchers”, hire them out of OpenAI or whatever, they'd probably be able to get a much bigger leg up from just technology transfer through those labs if they had set those up.

Jordan Schneider - Yeah, and this comes back to the other question, right? You had a big flow of really top-tier Chinese and Chinese American talent into China over the course of the 2010s where growth was high, the political system wasn't too noxious, it was getting less polluted, and people saw a really exciting future, both as a country to live in and make money.

I think the pitch that a Baidu or a DeepSeek has to a Chinese national working at OpenAI today is a lot worse than the type of pitch that you could make over the course of the of the 2000s and 2010s. You're still seeing very high percentages of Chinese PhDs in computer science in the U.S. want to stay in the U.S. Is that going to change at some point? Maybe. Does it matter? I mean, maybe AI becomes such a commodity and all the secrets get figured out that you don't need the actual best person and can do with the person who didn't end up getting into an MIT PhD but stayed at Tsinghua and can just read the papers and go to conferences and piece it all together.

I think it's an open question, but it does seem to me that the paradigm today — having the top, top minds — provides pretty remarkable returns relative to that of just having, like, the top 1% of people. And it's how we're seeing the likes of OpenAI be able to differentiate from these other organizations.

How has working at tech companies in China changed over the years?

James Wang - And I think one thing that you have also a unique perspective on is, as I sort of alluded to, you worked at a Chinese tech firm at one point. I know it was a little bit of a different time and place in terms of it, but curious about your thoughts on the culture and ecosystem. And if you still have contacts there, how do you think that it might have changed over the years?

Jordan Schneider - Yeah, I mean, I think this comes back to the, “is it fair” question. I mean, is it fair that like your Tsinghua PhD doesn't get to like play with, you know, Blackwell? No, it's not. It's completely unfair. It's, like, kind of awful.

That was the big takeaway for me spending a year at Kuaishou: these CEOs just want to grow up and be like Mark Zuckerberg. Be able to compete, be able to use the same products. They have the same mentality when it comes to working in the market. None of these guys want to deal with the Chinese government. Like the lamest, least cool thing is to do a national-strategic-whatever program. The mindset in the software ecosystem where I was most embedded was very much downstream of Silicon Valley.

And a lot of people, as I was mentioning earlier, had spent time either at Microsoft Asia or lived in California themselves. To watch them make a “life bet” on this Chinese tech ecosystem, which the government then was really aggressive towards the past few years, is kind of heartbreaking. At least, as much as one can be heartbroken for people who are living the best as anyone is in China as these software engineers and fancy technology firms.

So, it's just a big bummer, this whole politics stuff, but there's not much you can do about it because the CCP is the CCP. Xi has done what he has done to the trajectory of Chinese governance, and that has a lot of second order impacts, both for private sector entrepreneurs in China as well as the rest of the world's policymakers and how they're going to relate to Chinese folks going forward.

None of these guys (tech CEOs in China) want to deal with the Chinese government.

Will things get better between U.S. and China?

James Wang - And we talked a little bit about succession and other things, but do you think conditions will ever normalize between the two countries—within hopefully our lifetimes?

Jordan Schneider - So I had a fun conversation with Orville Schell on this. He's sort of like one of the deans of American-China studies. He started studying Chinese in like the 1950s and first made it over there in the 1970s. And he's gone through a lot of different arcs where, you know, he was one of the first academics to be let in. He was living there in the '80s. He wrote books about Tiananmen. He got kicked out and then he got let back in during the 2000s and 2010s. And now he's persona non grata yet again, because he has more hawkish views about the future of U.S.-China relations.

Now, I asked him, I was like, "Look, I do this podcast. I talk about sensitive stuff. I would like to go back to China again." He's like, "Jordan, I've been wanted and kicked out four times now. Don't worry, they'll want you at some point. These things come in waves.” I think it's sort of difficult to paint scenarios right now of China wanting to reform. It was also difficult in 1970 to paint a vision to paint a vision of reform and opening, right?

So I think history is weird and contingent. There's a great book called "The Middle Kingdom and the Beautiful Country," which goes back from 1776 until, I think, 2010, about all of the different ebbs and flows you've seen in the U.S.-China relationship. So I would bet that 10 years, 15 years from now, we'll see a difference and hopefully a more rosy relationship between the US and China, as Chinese leaders or the next Chinese leader understands that there's just more to gain from having a different relationship with the world than the one that Xi has clearly driven the PRC into.

And so, you know, I don't think this is vain hope. I think these things are not set. It's been a pretty dark five years, but I have more hope that things will get better than things will get worse.

James Wang - Awesome. I think that's probably a good note to leave it on. Thank you very much, Jordan.

Jordan Schneider - Well, this was fun. Thanks for having me!

China's AI Journey