Deep Tech Startups Are Not Software Startups

Or why AI and “Software/SaaS” are apples and oranges

One of my predictions for what’s coming next in 2024 is challenges for traditional software/SaaS investors in AI (and deep tech in general). This is because deep tech investing doesn’t look much like software/SaaS. As such, if you try to use the same playbook, you won’t have a good time.

Here, I’ll illustrate some major differences, using highly conceptualized, “Stratechery-style” doodle charts.

These are, of course, generalizations and largely conceptual rather than literal. Nonetheless, I think this is a useful framework to keep in mind on why this generation of startups is not like what most VCs have been dealing with for the past two decades.

In this article, I’m mainly going to be combining “software” and “SaaS”; most software these days is delivered in a SaaS model anyway—but even before it was, most of the characteristics like zero marginal cost and low upfront cost still held, even if the distribution/payment mechanism turned into a service.

For those who don’t follow startups/venture all day, SaaS is “software-as-a-service”

SaaS has a gradual ramp-up, deep tech tends to go from zero to huge

Many specialized metrics have developed in the two decades or so that SaaS has ruled the venture/startup landscape. Churn, CAC (customer acquisition cost), ARR (annual recurring revenue), Magic Number, etc have all become fairly common tools used to evaluate whether startups are doing well.

This works because upfront costs for software companies tend to be low, and a SaaS company especially can gradually acquire small numbers of customers—and then increasingly large numbers of customers—to ramp up their growth. This means you get an exponential curve, though, like any exponential curve, the beginning is flat, or almost linear.

Regardless, a gradual ramp means you can put in a bit of money, check how the startup is doing, and then put in more if it’s going well. You don’t really need much content knowledge here. If ARR is going up, and CAC is reasonable, churn is low, and the magic number looks good, you’re (probably) in good shape. If it’s SaaS for sales people, lawyers, or dogs, who cares? It’s all basically the same.

Unfortunately, this doesn’t work for deep tech. We recently had a company that essentially went from zero revenue to negotiating a contract for $1B. That means that if all you’re looking at is point-in-time financial metrics, you would completely miss what is interesting about the company. You really have to understand exactly what’s going on with the technology, the development of it, and whether it’s compelling to the (usually) fairly massive customers at play in most of the industries that deep tech touches.

You get a slower start, but often get a faster ramp to a big outcome. That outcome, however, is frequently somewhat capped—which is the next interesting difference to talk about.

Deep tech tends to be “sell out” faster, SaaS tries to take over the world

One interesting thing to note in both charts I drew is that deep tech “stops” while SaaS keeps going.

Most deep tech companies have natural “endpoints.” Medical device startups sell to large companies like Stryker, Medtronic, and the like. Robotics companies get acquired by sector-specific strategics or bigger robotics companies. And, of course, all the AI companies are getting consumed by the big tech companies.

It’s not that deep tech companies can’t go for IPO or be strong stand-alone businesses—it’s just usually not worth it.

That’s part of the distinction about deep tech, after all. There’s greater upfront cost, but there’s also a greater ongoing cost. As such, there’s a greater premium for both startup and acquirer to economies of scale. Semiconductors, the “deep tech” of the prior era (which also has similar economics to current deep tech, and less like software) are an ultimate example of the benefits of scale. While chips individually are obviously not “literally zero marginal cost,” relative to the massive fixed costs at play, they might as well be once you get to a large enough scale.

Software, SaaS, and marketplaces (I’ll lump the last one in, since it’s mostly software-enabled these days, and behaves similarly, even though it has slightly different characteristics in other regards) usually have big promises where they keep raising seemingly unlimited amounts of capital to continuously grow.

This means that most deep tech startups will have diminishing returns after a certain point, and be looking at exits of around hundreds of millions (say, $300-700 mm) or, at most, a few billion.

The software startups that we’re now familiar with often talk about exit figures in the hundreds of billions of dollars.

Ironically, given how this plays out, it typically means that successful deep tech companies will exit much sooner than successful SaaS startups. These companies try to take over the world, even when they start hitting a wall for growth (and get to unjustifiable levels in hype cycles/frenzies).

The skills required for both investors and founders are different

We’ve gotten quite used to serial entrepreneurs in the SaaS space. Their short cycle time, low upfront cost, and ability to “check” how they’re doing easily means that certain founders can keep cycling pivots in the same startup, or go through multiple startups, rapidly.

That isn’t true for deep tech. As said, it takes quite a while for deep tech to “come to fruition” in an obvious way that shows up in a financial statement. Additionally, it just actually takes longer in terms of the technology at play. There’s a lot of standardized tools/stacks now to start a software company pretty quickly. That doesn’t exist for deep tech companies, which are often one-of-a-kind. The tradeoff is that deep tech usually has a lot of IP value and moats… while SaaS frequently has nothing except speed-to-market and “user niceties” (including UI, customer service, etc.).

This means that deep tech companies have to get their market right (or else they can’t pivot) but also be patient. Founders obviously are on the “patient” journey, whether they like it or not, but investors also have to have that mindset going in. Additionally, investors in deep tech must have a level of subject matter expertise to be able to evaluate the technical milestones, understand how well development is going, and also have a sense of whether or not what’s being developed hits the needs of the market. That’s a lot of specific understanding that isn’t usually as critical—even if it’s useful—for SaaS investors.

So, is AI deep tech or software?

From a very literal perspective, AI is software. I mean, literally, it’s written in software.

However, that’s a fairly trivial definition. The question here is as a startup model, does AI have deep tech economics, or software economics?

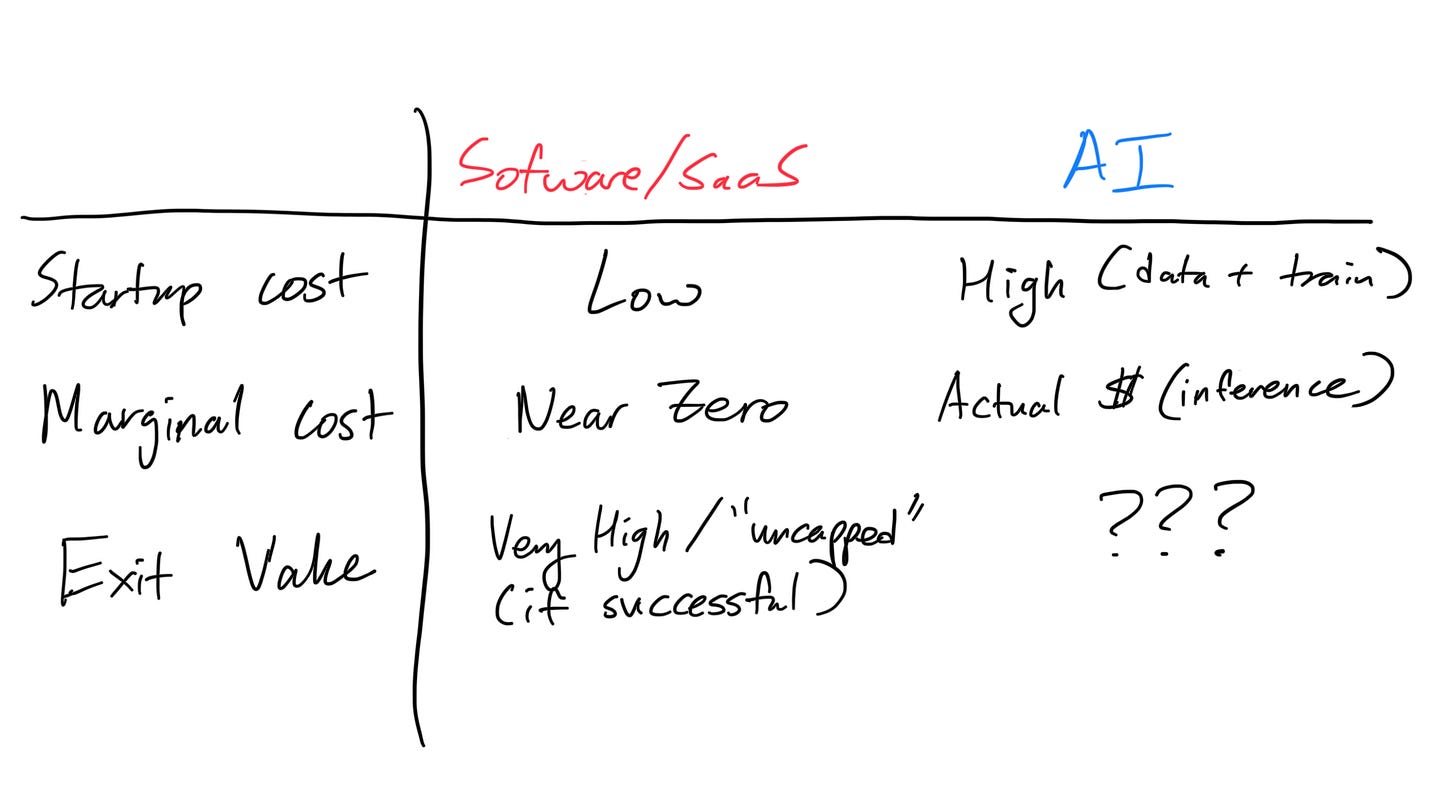

The key insight for why software/SaaS was so unique was low upfront costs and zero marginal cost for serving customers. That was always core to the investment thesis and models of how software startups developed.

So, is that the case for AI?

Given our prior framework in startup/upfront cost and marginal cost, AI does not look very similar to an AI startup.

An AI startup needs data (which can cost a lot to gather) and training (which can cost a lot to run) before ever serving a single customer. Additionally, while each use of the AI may not be that expensive, it’s muchpricier than a single “serving” of software. If it wasn’t, AI companies wouldn’t be so hungry for financing to keep up with compute costs (OpenAI would go bankrupt in fairly short order if it was cut off from Microsoft’s provision of cheap compute capacity).

The only big question is whether exit values are “capped” or whether AI companies can “keep going” in the same way as SaaS companies usually do. That is too early to tell. The proponents of “foundational models” certainly believe that it’s unlimited. I, on the other hand, am deeply skeptical of that notion.

Interestingly, if we call back to an older model of venture capital, we could probably scratch out “AI” and put in “semiconductor startup” (well, the more modern “fabless” versions) and it would fit just fine. Obviously, in the semiconductor space, we did have a lot of large companies—but those also had more “capped” exits, even as they continued to grow over literal decades in the public market.

Anyway, to understand why deep tech—and AI—is so different, you have to analyze its characteristics, which I think too few people have done in the current environment.

Most investors mistakenly apply the SaaS model to AI, assuming that scaling will magically produce strong margins. They’re wrong—and you, James, have brilliantly explained why. Thank you for that!