No, AI Power Requirements Aren't Intractable

AI’s Electricity Appetite is Big, But Our Wallets are Bigger

Guest Post: Josh Blanchfield is CIO at Avos Capital Management. He was a former colleague of mine at Bridgewater, has incredibly sharp thoughts about markets, and, relevantly, now runs a commodity hedge fund. He is featured talking about nuclear power in my book and has interesting thoughts now about AI power requirements. He’s also starting his own Substack, which I recommend subscribing to!

There is a drumbeat of vocal analysts and pundits who don’t believe that we will be able to power our AI ambitions.

The latest example was from an Apollo executive who said, “The gap between what AI is demanding and what we have everywhere in the world on the grid in terms of generation and transmission is huge and will not be closed in our lifetime.”

A lifetime is a long time! As it so happens, this is a question we’ve been studying for a while now, and the more we dig in, the more we think the doubters will be proved very wrong.

Before getting into anything AI-specific, it’s worth stepping back and considering humanity’s track record when functionally infinite money is thrown at a problem.

When measured apples to apples, the amount of money spent on powering AI will dwarf the amount of money it took to figure out how to put a man on the moon with “computers” that were closer to abacuses than to the computer in my dishwasher. We ran highways and railroads across the US for much, much less. The Manhattan Project was a drop in the bucket by comparison. We developed a vaccine for COVID in record time, and the cost could have been covered by the loose change in Sam Altman’s couch.

To solve the AI power problem, we need some combination of:

Producing more of a thing—electricity—that we are already good at producing.

Improving the energy efficiency of technology—a thing we are also very good at.

To think this is the problem that will ultimately thwart our species fails the smell test.

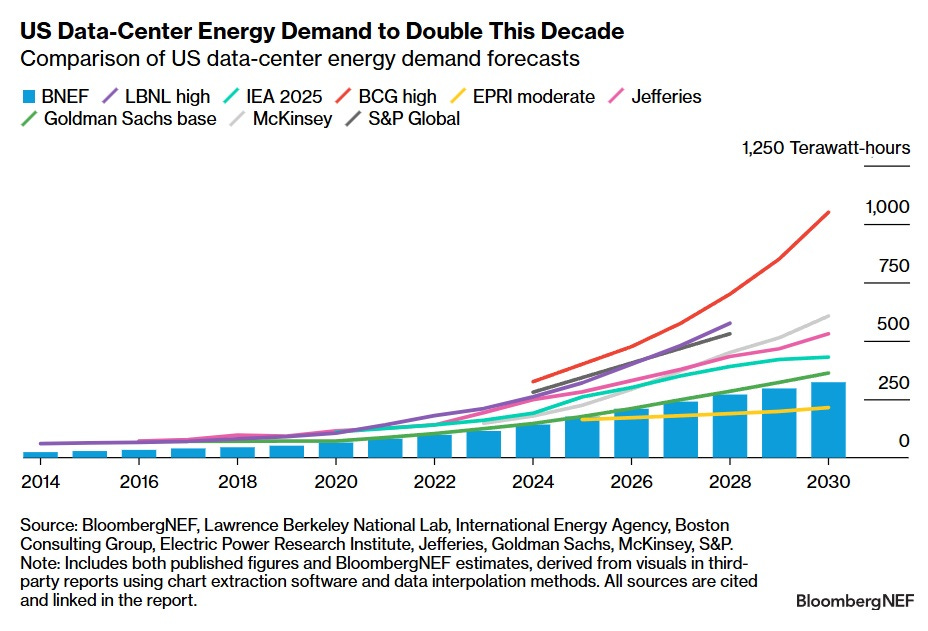

But let’s get specific. Here is a chart where a bunch of smart people sharpen their pencils and project how much juice all of these AI data centers will need. The estimates are comically different from each other: a ~5x range over the next 5 years.

For the sake of this analysis, we will pick the highest line from the chart: BCG’s “high” estimate at ~1000 terawatt-hours (TWh). We’ll use it because it is the most difficult bar to clear, even though I will eat my hat if the real number ends up anywhere close to that.

Current data center demand is about 200 TWh, so they think it’ll add an incremental 800 TWh. Current US total electricity demand is about 4200 TWh. So if you do the math, they are projecting an electricity demand growth rate of about 3.5% over the next 5 years.

That is high relative to recent history, but in a longer context it is completely normal—in fact, since 1950, US electricity demand has grown at an average of 3.2% per year.

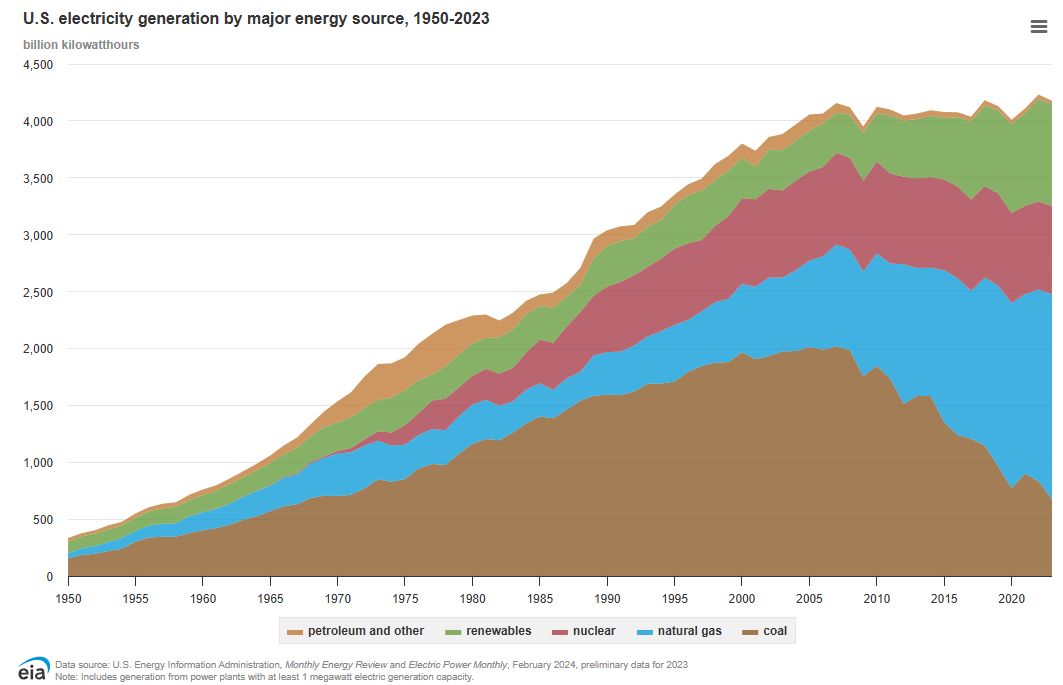

Where can we find 800 TWh? To start, let’s look at where electricity comes from now: the chart below from the EIA is labeled as “billion kilowatt-hours” instead of “terawatt-hours,” but those units are the same thing.

Some highlights from this chart:

Natural gas is now our largest source of electricity and has grown at ~3.5% per year for the last decade. If it continues at that pace, it will add about 300 TWh on its own, and that pace could certainly be dialed up. For all intents and purposes we have infinite natural gas, and it is super cheap. We think this will be the largest contributor to the solution.

Nuclear is too slow to move the needle. I wrote a piece in March titled “Calling Homer Simpson” that outlines why... you can find it here if you are interested: https://www.avos.co/research

Renewables have some issues as it relates to intermittency (that are tractable) but could easily provide most or all of the 800 TWh. As a point of comparison, China added 1400 TWh of renewables over the last 5 years.

Coal is an interesting wild card. It has gone from about 2000 TWh at the peak to about 700 now. Of that rough 1300 TWh reduction, we could get almost all of it back on a timeline that works. About half of the reduction came from just lowering the output of still operational plants, most of which could be dialed back up. The other half came from plant retirements.

How long it would take to unretire those plants is largely a function of political will. At the extreme, if Trump signed an executive order waiving permitting/studies/paperwork to do this (and it stood up in court), you are talking about a couple of years, maybe five years tops. Fast enough for the problem at hand.

As an aside, for years we’ve been hearing from ivory-tower types that unemployed coal miners should be re-educated to learn how to code. Maybe the universe has a dark sense of humor, and AI will take the coding jobs, and then coders will have to be re-educated to learn how to mine coal!

When you put it all together—even if you assume that the BCG high estimate is completely correct and the army of PhDs who are trying to lower the energy cost of AI are toiling away fruitlessly—we could probably cover the incremental demand by 2x if we went all hands on deck. And spending trillions of dollars tends to get a lot of hands on the deck.

Now... saying we can do this doesn’t mean there won’t be big hiccups. It will be incredibly hard and will require little to no wavering in financial resources and political will.

There are a zillion articles out there about the literal bottlenecks in materials and components, and they aren’t wrong—it is basically guaranteed that this won’t be a smooth process. Some part of the supply chain will get snarled, some protests will pop up and complicate permitting, there will be a blackout in some mid-sized city and associated outrage, etc., etc. But when we compare those issues to the financial rewards for clever humans to solve them, we see a footnote in history, not the main story.

Thanks for reading!

I hope you enjoyed Josh’s post. If you’d like to follow more of his work, subscribe to his new Substack and check out his firm’s research at Avos Capital Management.

Excellent piece! Drills down into EIA forecast, of 1200 TWA increase over 10 years. I took this as a Fate Accompli in piece I wrote on my substack a month ago. Good stuff.

I think 5 years is an ambitious timeline for expanding any capacity beyond current shovel in the ground projects.

But you are probably right, with serious mobilization now, over a 10 year horizon substantial onshore capacity could be installed.

Let me know your thoughts!

https://open.substack.com/pub/brynjo/p/the-perfect-storm-when-green-ambition?utm_source=share&utm_medium=android&r=7otr1

It sounds like the US government will be subsiding the AI companies.

https://substack.com/@dekleptocracy/note/c-175333104