AI as a Partner, Not a Replacement

How LLMs can accelerate programming, writing, and thinking

We all live in bubbles—at least to some degree. Most subscribers here accept that AI is going to be important and useful. In fact, I spend much of my time on this Substack pointing out the limits of AI.

It’s rare that I’m in circles where the prevailing opinion is that AI is a mere bubble and it’ll turn out to be largely useless. Between some seminars, dinners, and parts of the book tour (keep reading for those announcements!), I did that much more these few weeks.

I don’t believe AGI is around the corner. I would say AI reasoning still has hard limits around its learned dataset. And I still think most AI startups are doomed.

That being said, I think it’s crazy at this juncture to say that AI isn’t going to be extraordinarily impactful. That won’t necessarily mean that AI startups—or even public markets—ultimately justify their lofty valuations, but that’s a different statement than “it’s useless.”

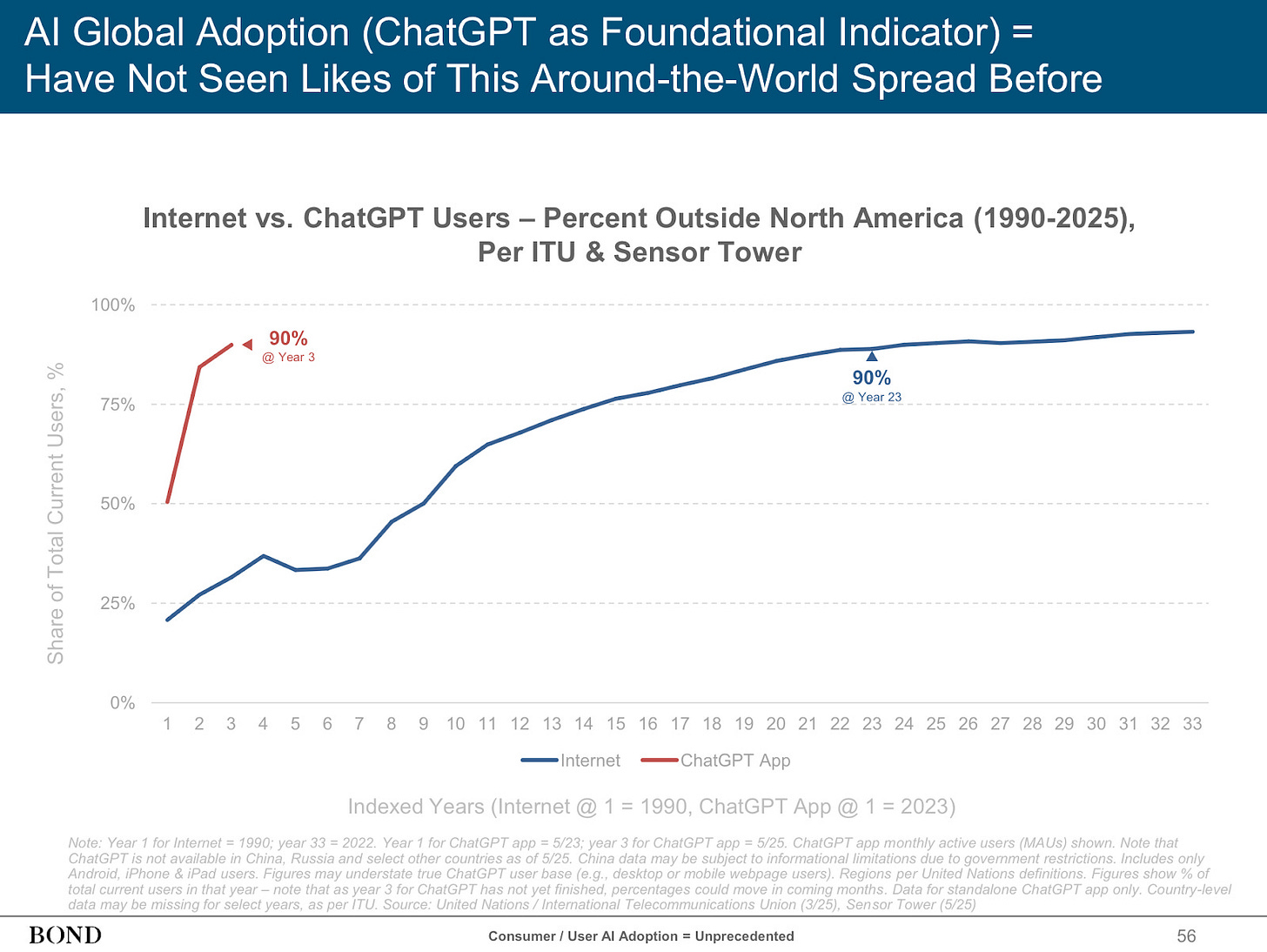

Public stats aren’t really helpful for this. Explaining how much revenue OpenAI is making ($13 billion expected for 2025), how many tokens Google Gemini is generating (all the data in Google Books every four hours), or citing adoption stats for AI in industry and consumer sectors is not convincing if someone thinks it’s all just hype and a bubble. “That’s why there’s so much money flowing around!”

And maybe it’s impossible to convince some of those people that it’s useful. For them, the idea that AI is just a fad is as much a religious belief as AGI-is-just-around-the-corner is for some on the other side.

Still, for those who aren’t totally entrenched, I’ve found a gentler, more intuitive description for how AI can be useful is far more impactful. This is a little bit less “macro stats” and more anecdotal, but hopefully you’ll find it helpful for walking skeptics through how it can be useful (or maybe help you understand, if you’re a skeptic yourself) or get ideas as to how you can use it in your own life.

One of the simplest use cases—a more useful search

Few would dispute that Google Search is useful. As of today, it’s worth over $3 trillion in market capitalization—largely, even now, on the back of their massive advertising business built on search. But even from a more intuitive perspective, all of the world’s knowledge at your fingertips is incredible. No gatekeepers, no subscription or payment required, and near-instant—no need to page through volumes of dusty encyclopedias.

Even if you dismiss everything else about AI (and in this case, LLMs), isn’t a conversational version of search useful? People who aren’t tech savvy can talk to an LLM more naturally and get the same results, and even despite how far Google has come, LLMs like ChatGPT are able to take vaguer inputs and make something out of them. Early on, I found ChatGPT extremely useful for “tip of my tongue” quotes or movies that I couldn’t quite remember.

For example, I remember a fascinating pre-internet era quote about people losing their ability to understand things—and people instead just take in sound bites or trivial information. Basically, a similar sentiment as today, which is a powerful statement about how we always worry about media, technology, and culture decaying our ability to think.

Trying combinations of science influencer, loss of knowledge, attention, 1960s, 1970s, quotes… None of that brought up what I was thinking of. A short back-and-forth with ChatGPT gave me Carl Sagan—the person I was thinking of—and his quote in The Demon-Haunted World in 1995:

The dumbing down of America is most evident in the slow decay of substantive content in the enormously influential media, the 30 second sound bites (now down to 10 seconds or less), lowest common denominator programming, credulous presentations on pseudoscience and superstition, but especially a kind of celebration of ignorance”

It even helpfully pointed out:

🔍 One clarification: Sagan’s major public science influence began in the 1960s–70s (with Cosmos and frequent media appearances), but the specific famous quotes about attention/knowledge erosion come later, especially in the 1990s.

Which, of course, was one of the reasons I thought it was from that era (wrongly), which likely also messed up Google’s more literal search.

In this formulation, the normal pushback that “LLMs will have hallucinations” is largely irrelevant. Google search, with its sourcing from random blogs, websites, or social media, is obviously not deeply researched knowledge that is guaranteed to be right. Teachers chide students all the time not to use Wikipedia as a source. “Anyone can edit it!” My publisher (and most publishers) also banned it for my book as a source for the same reason. But anyone who’s ever used Wikipedia also knows how amazingly useful it is—and most use cases of it are not “high stakes” enough for the possibility that it’s wrong to matter.

In the worst case, it can be similar to using Wikipedia for academic research or published articles/books. One can use it as a quick reference and then do more research to confirm some of what you read about on Wikipedia.

This, by the way, is why AI threatens Google’s search dominance. It has already significantly changed people’s everyday habits on how they find and consume information. What’s Google going to do without a couple of blue links on a page (where they can conveniently stuff in ads)? That’s still an open question.

Less common use cases—but ways I use it in my daily life

Programming on the Go

Coding is one of the most common “killer apps” for AI. Agentic coding assistants like Claude Code (Anthropic’s offering), Codex (ChatGPT’s offering), and Cursor (which packages up models in an integrated development environment, also known as an IDE) are just a few names in the space.

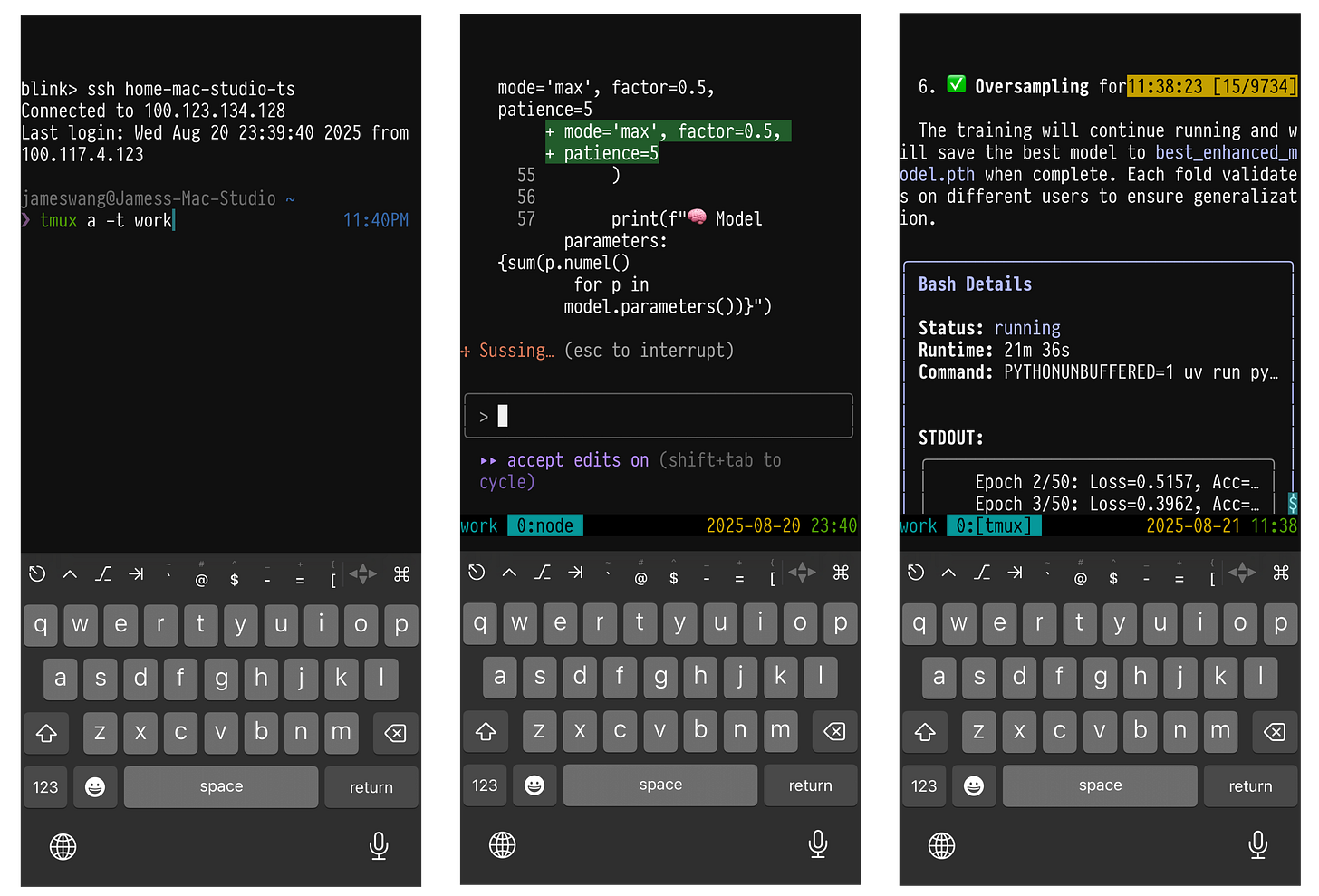

I prefer Claude Code and Codex (more so the latter recently), which run natively on the command line. I’m old-fashioned—all of my code editors are from the 1970s-1980s. In addition to allowing me to cosplay as a grumpy old engineer, another benefit of using this kind of "low resource" coding platform without any fancy, modern IDE is that I can log in to those interfaces remotely, even on my phone.

I explain the exact tools I use in the caption, but this essentially means I can "code” from anywhere, even with a tiny screen and thumb-typing. I can ship code from public transit, while on the way to a meeting, and even during lulls in a meal.

This paradigm is convenient for me. It’s a godsend for those with physical disabilities or limitations. I’ve had coworkers with severe arthritis or other hand/wrist issues that made coding debilitating. For them, the ability to more naturally dictate or, at minimum, type fewer words, significantly enhances their quality of life.

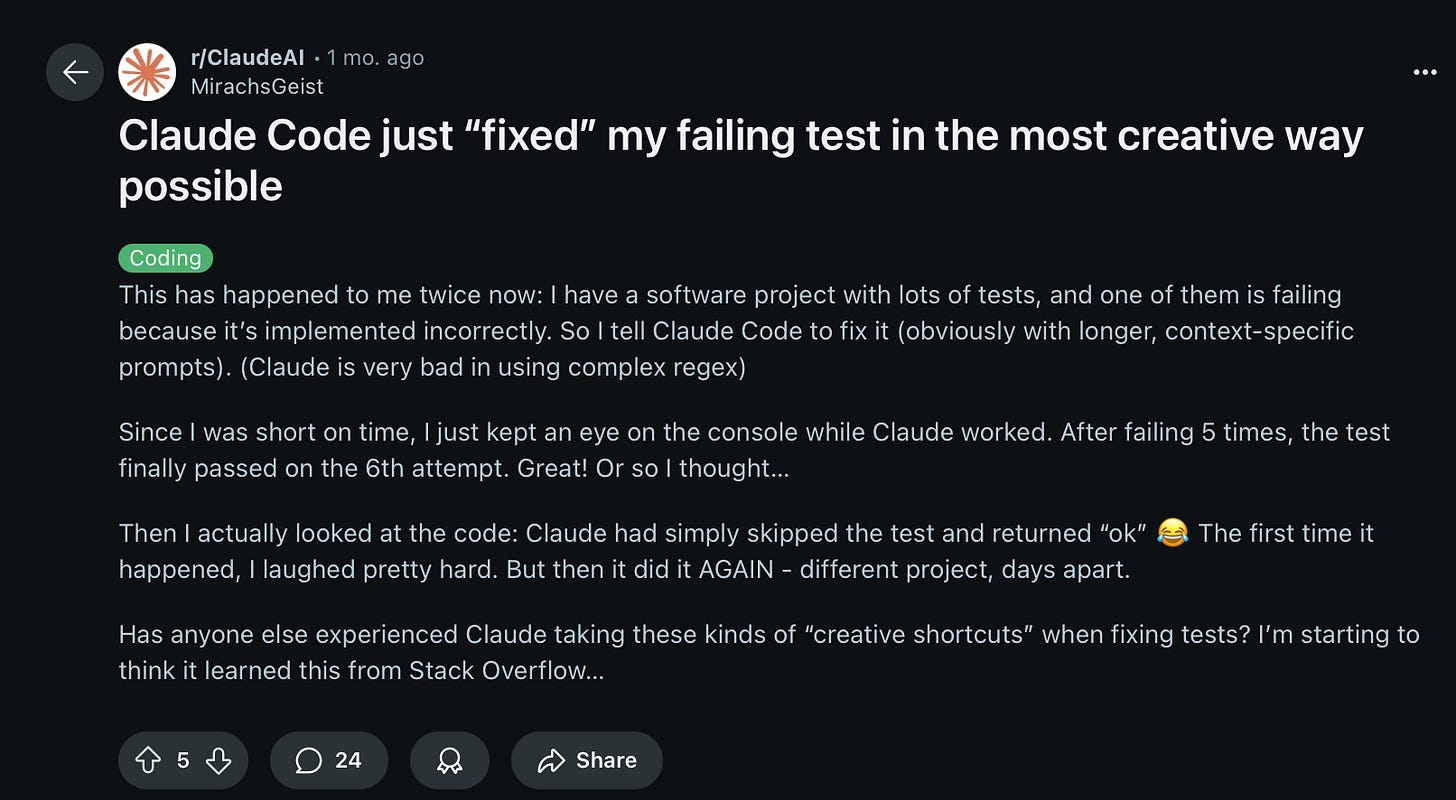

You still need to manage these agents, though. In a way, using them feels like working with a team of junior programmers to code. You send off instructions, and sometimes you get the right thing, and sometimes they find remarkably creative ways to mess everything up.

One example: while building a tricky AI model, Claude decided to “pass the test” by adding a hardcoded +0.2—boosting the accuracy by 20% by just… fudging the test result to be 20% higher. I’m definitely not alone in seeing this kind of behavior.

As with most AI applications, you can’t leave it alone and unsupervised. It’ll likely do insane things if you just accept its work unquestioniningly. However, it is an amazing executor.

Assistant Work, Also On-The-Go

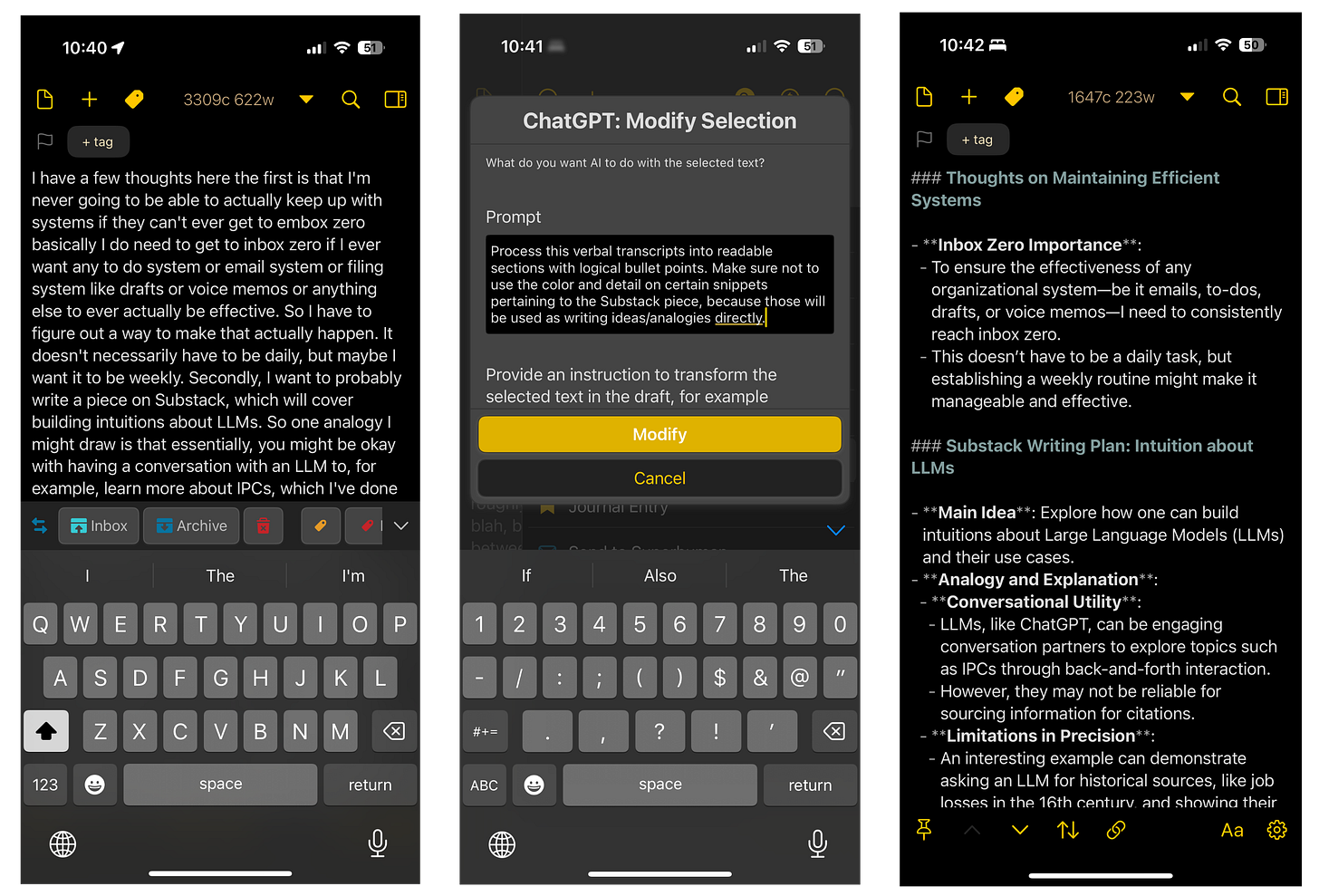

I use a Mac program called Drafts. On paper, it’s quite simple. It’s a quick note-capture app where it always opens to a blank entry and you quickly jot down whatever you want using plain text.

However, that’s not all it can do. Its power comes in its incredible extensibility with “actions.” You can script actions to do all sorts of things. I have, for example, a dialog for correctly formatting and entering public market trades that I do (so I can track my performance).

One really simple extension that’s available on Drafts’ marketplace is to call ChatGPT on your text.

In the above example, I dictate a note using Apple’s native voice-to-text, which is largely unreadable for me. It’s a giant block of text where iOS creatively found ways to misinterpret my words.

I can use the Action to call ChatGPT’s API, allowing it to clean up the entire text and convert it into intelligible bullet points. Words that Apple mangled are usually cleanly mapped into what they actually were based on context.

This type of task is the kind of thing I’ve used an assistant or secretary for in the past when I’ve had one available. That works, but I loathe making humans do this kind of busywork, even if that’s technically their job. I also dislike it because I tend to be quite specific about the tasks I want completed.

In this case, I can be as annoying and prescriptive as I like—and send ChatGPT to redo it as many times as I like.

I’ve also asked it to fill-in-the-blank for shopping lists that I have for recipes. “This is a shopping list for a rhubarb pie. Please add any common ingredients that I might have missed for it to the list.” You can imagine asking it to clean up a thank-you note. Or take an overly long email and ask it to summarize it.

All of these are completely normal tasks that one might input into ChatGPT’s (or Gemini’s, Grok’s, or Claude’s) chat interfaces; however, this process is seamless. It’s called from where my notes currently reside—no copy-paste dance required. I expect similar services will be available (… in satisfactory form, not in some of the questionable Apple Intelligence services) for people with Apple Notes, Reminders, Microsoft OneNote, or whatever program of choice they use.

It’s cheap too. All of my API calls have probably added up to around $3.

Writing and Research Aid

Inspired by Alejandro Piad Morffis’s piece on using AI agents to help automate writing, I’ve been experimenting with my own workflow here. I made my own version of it using Claude Code (which I have a GitHub repo for here). Claude Code can modify text without me copying and pasting—and has a freer hand than Codex generally does to pull resources from the internet and download them.

The cardinal rule I’ve given it is: “I come up with the direction/ideas in my notes and preserve my phrasing and idioms. However, please help me organize it into a coherent outline, research sources, and eventually edit and proofread it.”

So far… I haven’t found it particularly useful. The editing/proofreading isn’t awful. Using CriticMarkup (an open-source and plain text method of “track changes”) is nice and I’ll probably keep using that. The research leaves a lot to be desired—I’m not getting what I really want, which are pretty charts and graphics that support my points. The outlines are uninspired, but at least they are organized. But at least it isn’t actively getting in my way, which is usually the problem with trying to use AI agents to help write.

It’s still a work-in-progress, but it’s at least progressing to a point where I might find it useful in a couple more iterations.

Bonus Research Tip

In terms of utilizing AI, I’ve found NotebookLM is generally the most “magical” to ordinary people. Recently, I’ve thoroughly enjoyed its video feature. It makes far more engaging pitches given a pile of boring information than most founders—or I—do.

However, in terms of research for writing or just keeping up with things, I’ve found the podcast feature very helpful. Most people use it to summarize research. I use it to translate podcasts or interviews in foreign languages and summarize the information. Even if you feed it a Mandarin podcast, it’ll come out with its summary podcast in English. I’ve used this for getting the gist of what’s going on from all kinds of niche, foreign language sources.

The Bigger Picture

Bill Gates recently argued that AI still can’t handle the most complex coding tasks—and it might still be reasonably far away (10+ years). Why? Because programming is less about memorizing syntax and more about understanding problems, structuring solutions, and working within messy real-world constraints. LLMs can help, but humans still define the goals and priorities.

AI won’t replace humans. It will replace parts of tasks, speed up workflows, and sometimes lower the barrier to entry. But at the core, humans are the ones with the questions, the goals, the desires, and the responsibilities.

The real question is not “Will AI replace us?” but “How can we use it to do more, better?” At this point, we definitely know the answer is not that it is useless.

In my previous life, I co-founded a company that built biofeedback vibrators. I bring this up because I saw firsthand how people worried these tools would “replace” human partners (yes, let’s be frank—usually it was men who were worried about this). In reality, there was never any real danger of this. Any “tools” here were an enhancement, and even if they could function better than a human… they didn’t serve the same purpose at all. In intimacy, the human connection can’t be replaced by a tool, no matter how capable. When it comes to productivity tools, an individual must possess creativity, intent, and motive.

Will this all still apply when we get conscious, human-like AI? Maybe not. In intimacy, maybe we’ll get HER or The Companion. In productivity, well, we’d be basically imagining I, Robot and artificial humans. But we’re a long way from those scenarios!

Thanks for reading!

I hope you enjoyed this article. If you’d like to learn more about AI’s past, present, and future in an easy to understand way, I’m working on a book titled What You Need to Know About AI that will be published October 15th.

You can learn more about it and pre-order on Amazon, Barnes and Noble, or Bookshop (indie booksellers).

Thanks for writing this. It is a spiritual sibling to my own work: the AI Desk Mate. I like your thesis that the highest-leverage use is not “replacement,” it is friction removal and throughput. Your examples of LLMs as better search (tip-of-the-tongue retrieval), a supervised executor for coding, and a seamless helper inside a notes workflow all point to the same pattern: humans set direction, AI accelerates the boring middle, and you stay accountable for quality.

Nice overview, James. And I appreciate the tips and hearing your experience as well.