Bubble, Bubble, Toil and Trouble

Financial vs. Technological Bubbles

Quick note: My book What You Need to Know About AI is just $5 on Kindle this Black Friday week only (through Dec 1). If you’ve been meaning to check it out, now’s a good time! Check out the deal here.

And if you prefer physical books, you can find signed copies at select local bookstores—full list here.

Most people don’t understand bubbles.

The popular conception of them is that investors get greedy and stupid. They make crazy, irrational investments and then lose their shirts. Or, if you’re more conspiratorially minded, the elite get out at the top and everyone else holds the bag. And, of course, there are heroes who call it. In popular retellings of these periods, like 2008, such as in The Big Short, these come in the form of contrarians like Michael Burry (Christian Bale) and Steve Eisman (Steve Carell).

Don’t get me wrong, I really like that movie—for another perspective, I’d also suggest Margin Call.

Those movies aren’t bad in terms of accuracy in capturing certain aspects of finance culture and some of the events. They are, obviously, oversimplified. Painting a little more in black-and-white than reality is a useful cinematic tool.

But if we’re really going to talk about bubbles, not all of them are created equal.

A Bubble, Again?

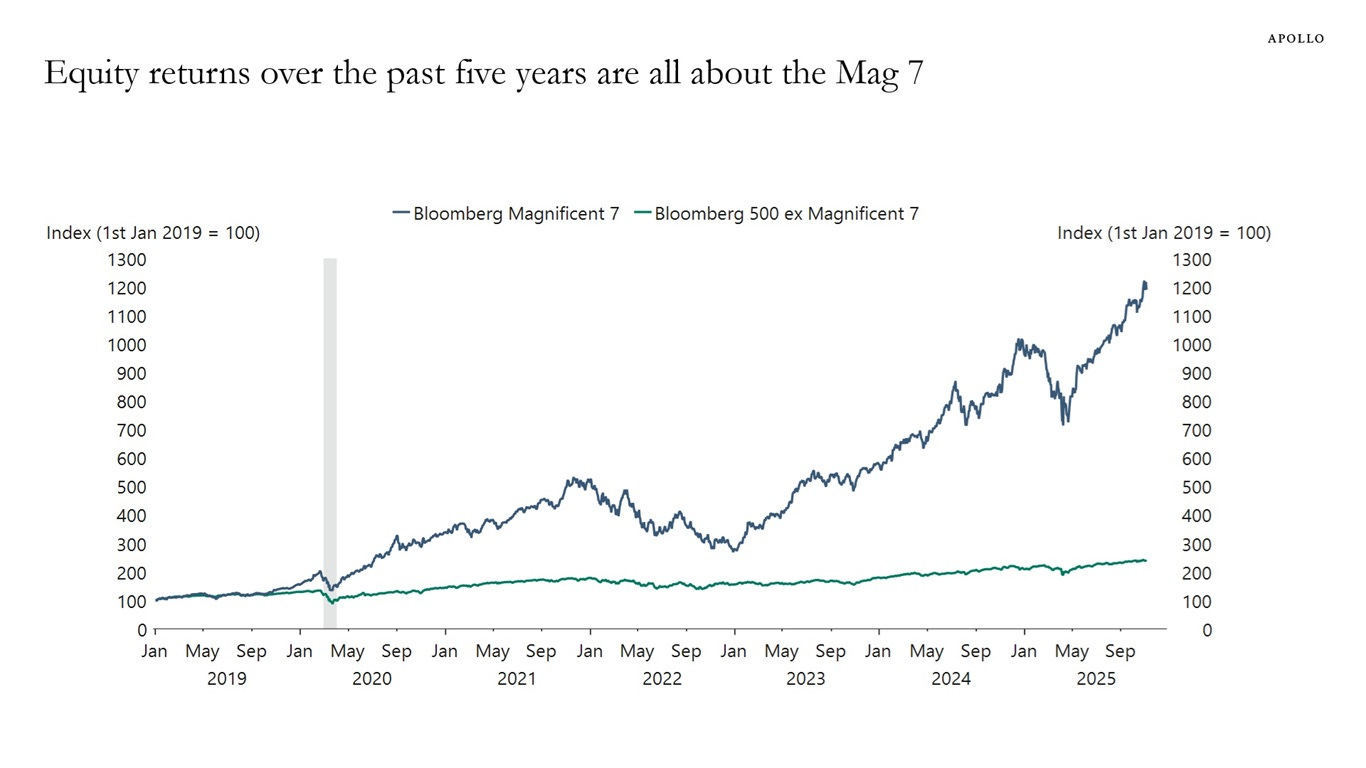

Why am I talking about this now? The nominal reason is recent chatter about AI being a massive bubble—especially in light of the Magnificent Seven’s ridiculous divergence from the rest of the market, historical highs in US equity forward P/E ratios, etc. And, of course, OpenAI’s somewhat crazy, eye-popping machinations, like the $300B deal with Oracle, or AMD’s rather strange chip deal, just to name two recent ones.

Of course, this narrative was also around last year when OpenAI’s revenue was $3.4B (it supposedly will top $20B this year). I know because I had to write a piece addressing the point at the time.

Financial and Technology Bubbles

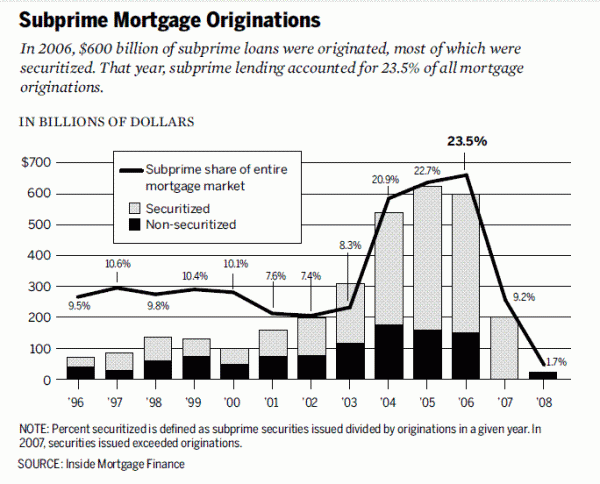

We’ve had all kinds of bubbles. Some are speculative financial bubbles—the mortgage crisis in 2008 (Global Financial Crisis) comes to mind. Or the Dutch Tulip Mania in the 1630s.

Others are technology bubbles. American railroads at the turn of the century. Or the Internet boom and bust in the 1990s and early 2000s.

Regardless of anything else you take away, you should note that these are not the same thing. You might get insane price appreciation and crazy financial speculation. People may lose their shirts. In both, players all look back at it like a really bad drug trip or a poorly considered weekend in Vegas (or Atlantic City or Macau—just to be more inclusive about it).

But it’s not the same thing.

Financial Bubbles are Predictable—Kind Of

One of the key plot points for both The Big Short and Margin Call is that smart people with sharp pencils figured out the multilayered, complicated structures of CDOs (collateralized debt obligations), MBS (mortgage-backed securities), etc. were built on bad assumptions about default rates and their correlations—making them a house of cards. Could it have not collapsed? Sure, if interest rates didn’t go up, the economy stayed super strong, etc.

It’s not a foregone conclusion it was going to collapse. It’s just a very likely one. It’s a nice, happy popular media narrative that the public likes—those greedy, anti-social math geeks screwed everything up (hmm, wonder if that might be the case for AI too…).

Obviously, by my tone, you can infer that I think it’s not that simple.

It’s a matter of degree

Bundling mortgages isn’t actually a stupid idea (if it were, we’d be in trouble right now… and way fewer people could afford houses). Diversification is a real thing.

The “leverage” and “debt” story isn’t even the problem. If it were… what are we doing offering mortgages anyway—or college loans or anything else? Or, you know, microfinance loans for impoverished borrowers in West Africa (like where I used to work). It sure would be news to all those non-profits trying to help borrowers finance their inventories of bananas, textiles, or other trade goods that they’re committing some kind of moral evil.

It isn’t stupid to think that getting people into homes (or educations) before they earn every last penny to pay for it out-of-pocket is a bad thing—if it’s even possible to do so. It isn’t a stupid thing to think that the mortgages in California vs. Utah would have different characteristics and hit trouble at different times.

What might be stupid? Well, leveraging to the absolute hilt and also assuming that correlation assumptions are sacrosanct and can’t be violated (i.e., there can’t be a nationwide recession).

Food isn’t a bad thing, even if overeating is. Moderation in eating for health is not a bad thing, even if anorexia is. It’s a matter of degree. And, yes, that degree can be “measured” even if it’s not super predictable when bubbles pop—the entire mortgage thing worked until it didn’t, and a confluence of a couple of economic hiccups helped push the thing over the cliff.

(And yes, for the conspiratorially minded, hedge funds don’t tend to “correct” or “price discover” the right levels—it’s stupid to fight the market, which can, as Keynes noted, “stay irrational for longer than you can stay solvent.” TSLAQ have discovered this to their sorrow—however right they are about Tesla. And academic papers have found that hedge funds usually ride bubbles, not fight them.)

Technology Bubbles are About Predicting the Future of a Totally New Technology

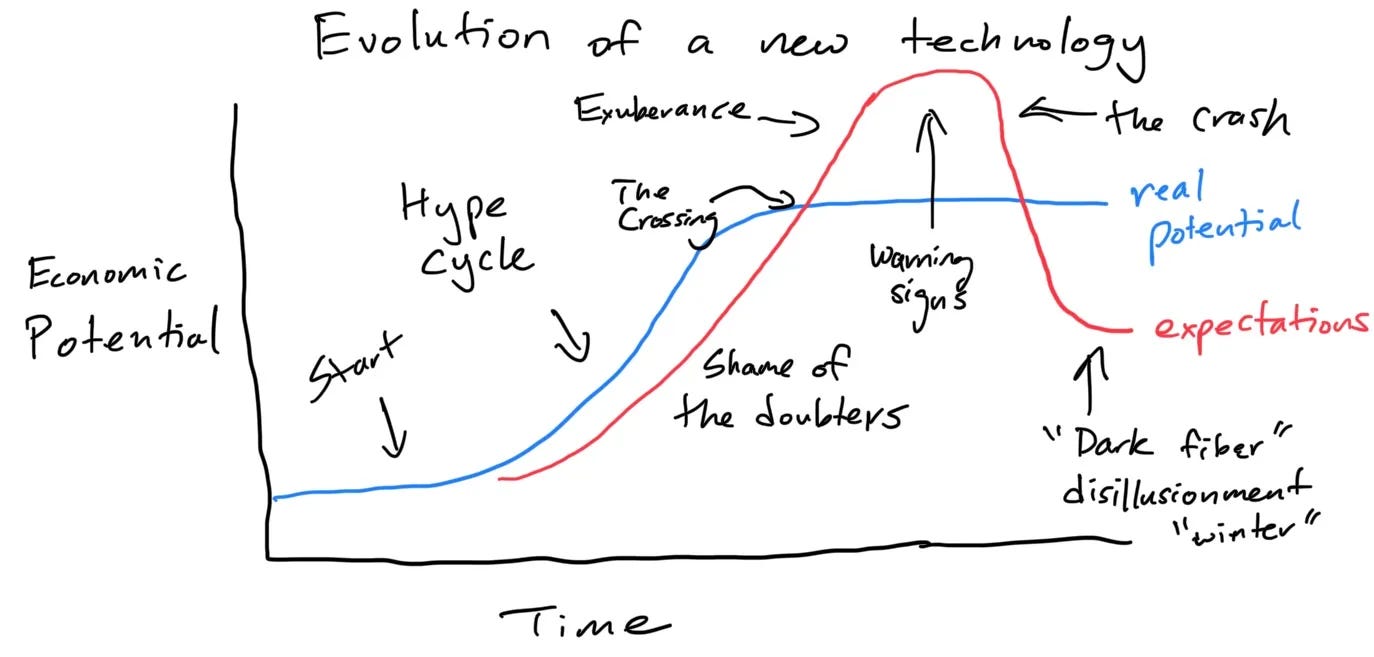

Going back to my prior hand-drawn framework, the problem with trying to “predict” tech bubbles is no one quite knows where the tech will go.

In 1952, this is what one article predicted we’d have in the year 2000:

By the year 2000 cures for most of the diseases of man will have been discovered. The average age will be about 100 years. Journeys through space in rocket ships will be an established form of transportation, with regularly scheduled trips to the various planets. A number of man-made moons will be circling around the earth.

Is that right? No. Obviously, we fell quite short on certain aspects. However, our level of computing miniaturization, the advancement of our biotech (because it wasn’t as understood how complicated it was back then), and numerous other aspects are much more advanced.

I’m not going to totally rehash my last bubble piece, but the point is:

I’m both saying tech bubbles are actually reasonable/rational… and highly unpredictable in the moment when our expectations truly exceed where the technology will go.

It’s one thing to be using purely historical financial models of default and delinquency rates for mortgages—any analyst should immediately see red flags in building in too much reliance on that. But hey, we have data on that. It’s quite another to try to guess what a totally new, never-before-seen technology (which, by definition, there is no data on) is supposed to get to.

A great example of how silly trying to precisely extrapolate and nail down a new technology’s value using the past is Aswath Damodaran (finance professor at NYU Stern)’s piece on FiveThirtyEight explaining why “Uber Isn’t Worth $17B” (he thinks it’s closer to $5.9B) and VC Bill Gurley’s deconstruction of it in “How to Miss by a Mile.”

The current market cap is around $175B.

The Real Revolution is “Gen2” of the Technology

In the immediate aftermath of the dot-com bust, many commenters talked about how stupid it all was. Dot-com everything. Eyeballs. Webvan with “online grocery delivery.” How stupid.

Of course, given most of the Mag 7 is composed of internet-related companies, and Google and Amazon became quite large companies (and, oh yes, Instacart, DoorDash, Uber Eats, etc. exist), I’d say that over two decades later, boosters of the internet may have had the last laugh.

Even the “dark fiber” of the Internet, the horrible, shirt-losing investments of the late 1990s and 2000s, helped become the backbone of today’s digital economy, as per this great piece by Justin Kollar.

Still, other than “actually, the dot-com bubble completely changed our world,” it’s useful to remember what predictions of it were. It’s really easy to take a super simple extrapolation: just stick everything online.

Many small-town publications rejoiced in the democratization the internet brought. Their tiny circulation numbers didn’t matter on the internet—they could get subscribers and readers anywhere. Of course, we know what actually happened. The destruction of geographic barriers not only meant a newspaper in Wichita, Kansas, could get subscribers from anywhere, but they were in head-to-head competition with The New York Times. They were no longer protected by locality. The New York Times, in a head-to-head competition, wins.

The market flows downstream to the best. This is the same as what we’re literally seeing now. While translators have seen significant job loss to AI, I interviewed certain translators who are particularly good at subspecialties like literature or legal documents who literally 10X’ed their work. They no longer have “bodies to throw at the problem” barriers for low-level, lower-skill work—AI can do it, and they can simply focus on the tricky parts and give the documents a quick once-over.

That’s potentially predictable. But, during the Internet boom, could you have guessed that web native advertising would, in turn, expand and eat a lot of the market? In other words, could you have predicted that not only would it be the best newspapers dominating online, but also players who were not newspapers at all, like Google or Facebook/Meta?

This is the problem in investing and predicting the top of a bubble. It’s really hard to know the form that technology will ultimately take. It’s inevitably going to fall far short in certain aspects (we don’t have Rosie the Robot Maid from the Jetsons)—but also going to be (literally) unimaginably more advanced in certain others. Especially since facilitating technologies in the meantime make a huge difference.

Webvan might not have been viable back in the 2000s, but broadband, fast cell networks, and smartphones made things very different for Uber and Instacart a decade or two later.

As any high school stats student should have learned, extrapolating without data is just stupid. That’s why “calling the top” of a tech bubble isn’t really an analytical exercise, unless you can literally predict the future.

So is it a bubble?

If it isn’t already, it will be (again, my constantly called-back-to piece on the AI bubble). Tech always turns into a bubble eventually. But that doesn’t obviate its societal/economic impact—and it also doesn’t make it easy to call when we’ve jumped from exuberance to irrational exuberance, except in hindsight.

Thanks for reading!

As mentioned, through Dec 1, the Kindle edition of my book What You Need to Know About AI is just $5 (regularly $12.99). If you enjoy Weighty Thoughts, the book is essentially the structured, front-to-back version of how I think about AI and where things may be headed.

LinkedIn co-founder Reid Hoffman called it “accessible to neophytes, but broad enough to offer useful insights even to AI professionals who often end up narrowly focused.”

If you’d rather read a physical copy (or want a giftable version) several bookstores carry signed editions, some with the coveted shiny gold bookmarks. You can find the list of participating shops here.

Whether on the screen or on paper, thank you, as always, for reading.

Love this!

“Whenever I see a bubble forming, I rush in to buy.” – George Soros https://blog.inverteum.com/p/speculative-bubbles-can-grow-wealth