When the AI Bubble Bursts

It’s when, not if, for these kinds of new technologies

OpenAI recently exceeded $3.4B in annualized revenue. However, every single source, including Ben Horowitz at a16z, acknowledges that they’re burning through much more money than they’re making.

Tons of AI startups keep getting started. They raise a bunch of money. And they hand a lot of that money to either NVIDIA (directly) or the cloud providers (NVIDIA, indirectly).

Some people briefly lost their minds when at the end of last week, NVIDIA fell by a little over 3%—which took them from the largest company in the world, to slightly smaller than Microsoft again (and about tied with Apple). I doubt this “slump” is going to turn into an all-out slide/collapse (and it might not even stick for long) even if it keeps going for some time, but it still hints at people panicking and worrying about whether it was a sign of the “top.”

Edit: I wrote this over the weekend, and NVDA continues to decline on Monday—we’ll see what happens, though I still doubt this is where NVIDIA collapses.

Everyone is frenzied, but also kind of jittery about when this AI hype cycle will end. Some predictions revolve around running out of trainable data by 2027-2028, but I think that this “trainable data” worry—if it’s even real at all—will not be a factor in bursting this bubble.

It’s going to be much more like how every bubble bursts: everyone realizes that their exponentially increasing expectations for what the new technology can do cannot be realized.

A history of bubbles

There are certainly speculative bubbles that do not involve technology. The Dutch Tulip Mania from 1634-1637 is one example. Most, however, do.

All of these bubbles share a fundamental characteristic. People’s expectations of future potential kept growing and growing, and eventually exceeded the actual potential. Everyone realizing that has occurred is when the crash happens.

(As a note, Manias, Panics, and Crashes: A History of Financial Crises by Kindleberger was one of the books new investment associates at Bridgewater were issued when I started. It was both one of the worst, driest prose books I’ve ever read—I never fall asleep while reading, and did so multiple times with this book—and also one of the most influential in my thinking about markets and economic history. Highly recommended.)

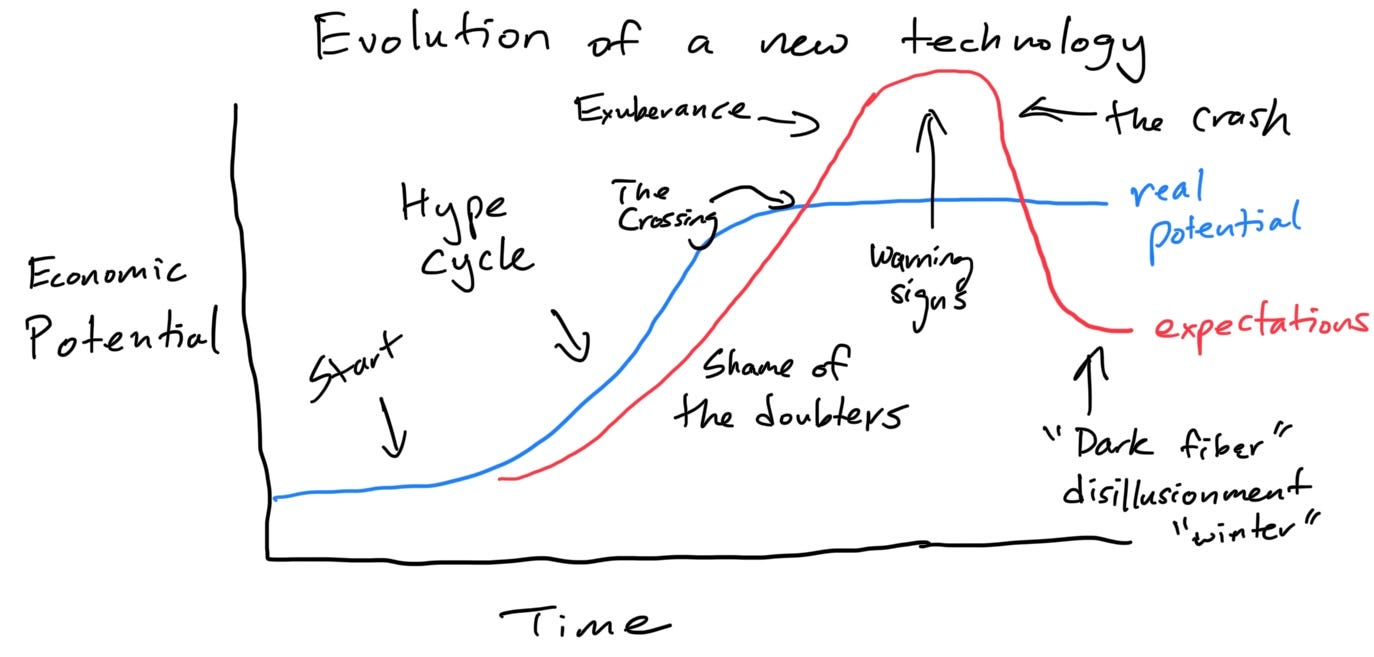

Above, I have a highly stylized version of how this occurs.

Stages

The Start: The true believers and early adopters start noticing how incredible the potential of the technology is. These evangelists talk about it without much interest from most people. However, some people begin taking notice.

Hype Cycle/Shame of the Doubters: Rapid growth, rapid progression, funding starts rolling in. Notably, this is the period of time that expectations keep getting exceeded—either in technological potential or just sheer funding pouring in. Either way, doubters, or naysayers either become embarrassed by their predictions looking silly or dated, or, in the case of investors (e.g., GMO during the Dot Com boom) lose massive amounts of money betting against the trend.

The Crossing/Exuberance: Unbeknownst to everyone, expectations exceed what the technology can do—especially since tech usually levels out in what it can achieve, but people’s imaginations (and greed) continues exponentially. This is where the traditional mania and craziness happens, with logic going entirely out the window (with the doubters getting shamed or losing their shirts)

Warning Signs/The Crash: It finally happens. Dumb things get noticed. Companies are starting to have a harder time raising money. Maybe interest rates rise (which is often a catalyst, either because of a central bank or because liquidity has already been sucked dry). Finally, everyone notices that nothing actually makes sense, and the crash happens in short order.

Disillusionment/Winter/“Dark Fiber”: AI winter. Crypto winter. Biotech winter. This has happened repeatedly where so much disgust and disillusionment sets in that expectations actually fall significantly beneath what the technology can do. Great companies get born (or survive) these periods, like Google and Amazon through the Dot Com bust, and quietly amass power with no one paying as much attention. Additionally, a huge amount of infrastructure is typically built—in the case of Dot Com, it was a bunch of internet infrastructure/fiber, which got picked up for cheap and was “overcapacity” at least until the quietly-getting-powerful companies utilize it and flex their muscles.

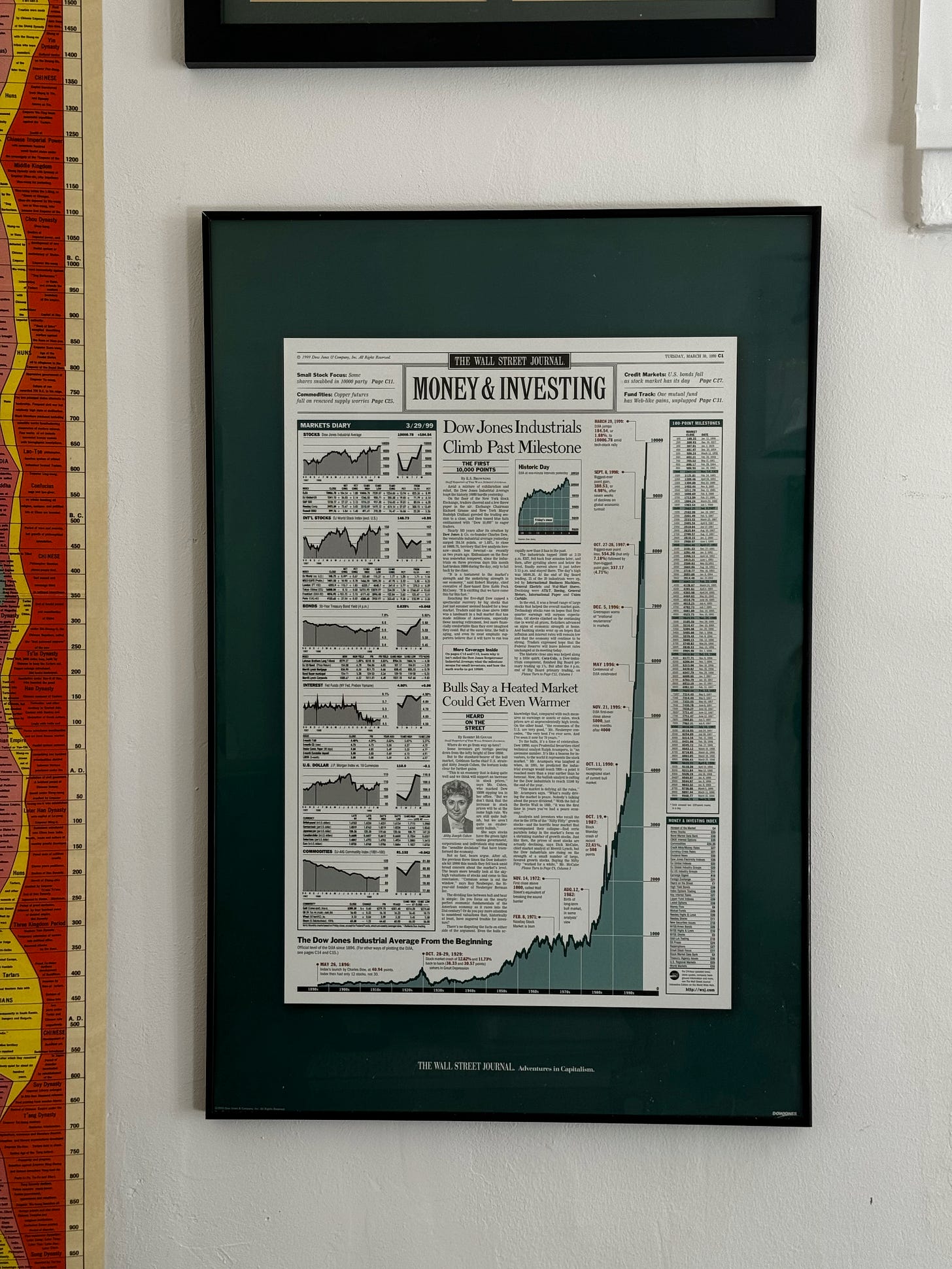

Note that this happens for many technologies. The Dot Com boom and bust is a touchstone of a lot of venture investors though—behind my desk is a triumphant commemorative Wall Street Journal poster from March 30, 1999, of the Dow Jones exceeding 10,000 points.

No, it was printed in 1999 and was not a parody.

Why can’t you avoid the bust?

The shamed, embarrassed naysayers who called the top (… potentially for years as things kept going up) become the oracles/prophets/smart people. As they say, everyone was dumb, and it was obvious this was all an illusion.

Why can’t people see that and avoid this boom and bust?

Well, as the saying goes, hindsight is 20/20. And, as you might have noticed by my somewhat tongue-in-cheek description of the naysayers, they rarely correctly call the top. If you follow what some perma-bears say—who, as the investment community joke, have called 14 of the last 2 recessions—you’d never invest in the technology at all… and would have missed out on the true, spectacular benefits.

The reality is: a new technology… is new. We don’t actually know, going in, what a new technology might actually be able to achieve. It’s why estimations at the start constantly undershoot, and then estimations at the end overshoot. It’s just impossible to know when that crossing point actually occurs because we haven’t actually had experience with the new technology before.

This happened with Dot Com/internet, crypto, SaaS, and biotech all within the past few decades. Before that, different types of semiconductors had this kind of boom/bust, and before that, railroads had the same kind of thing.

It doesn’t really matter what the technology is—it exceeds expectations, which is what draws attention, and then expectations exceed reality.

By definition, you can’t call the top because it’s a new technology that no one actually knows the true potential of yet.

Even scientists and “experts” will have trouble doing so. They won’t have trouble calling out straight-up fantasy on what the tech can’t do (or, in AI’s case, fantastical risks that have no basis in reality), but these experts have never seen the technology applied in scale within broader society/industry. No one has. Again, that’s what makes the technology new.

As such, while I roll my eyes at people predicting crazy things with AI, I do have sympathy for why people do go into a mania. I also think it’s part of the natural way (in fact, probably the “right way”) technology with high potential evolves.

So, have we passed the top?

Readers who clicked into this wanting to read about exactly when to dump all their NVDA shares will now have impatiently sat through an economic history lesson, or more likely have bounced from this article.

Astute readers will have probably realized by now that my point is I also would not be able to truly call the top for the exact reasons I described above.

I may be able to guess when we’ve hit “the Crossing” because I will have a sense of when valuation expectations require sheer fantasy to achieve. However, even in that case, “exuberance” (what we used to call “Animal Spirits” back in 2008-2010) can run for a long time, in which case you’d go bankrupt trying to bet against the trend.

If I were to stake a position somewhere, I think most all the foundational model companies are likely toast (and their valuations are pricing in pure fantasy). Note that I mean economically, in terms of what kind of return they can get out of the enormous investments at sky-high valuations, not technologically. I still think they have room to run technologically—which also applies to AI as a whole.

The current generation of AI is still young, is in the midst of rapid advancement in capabilities, and not-so-frontier techniques like overtraining are already giving pretty incredible results (let alone synthetic data, newer representations, and other things coming down the pipeline). As such, I don’t think we have actually hit the Crossing yet.

Am I right? We’ll see. But in any case, I can fairly confidently call that there will be a burst bubble by the end of this—there always is.

A great article about bubbles/cycles!

"Readers who clicked into this wanting to read about exactly when to dump all their NVDA shares" hahaha