Shortages Create Opportunity

Whether Real or From Export Controls

Let’s look at what happens when supply is restricted—whether through chip export controls or rare earth embargoes

On October 9th, China massively escalated the trade war with a package of rare earth export controls with extraterritorial jurisdiction. If Chinese-produced rare earths account for 0.1% or more of the value of the exported item (or are integrated in specified controlled components), a Chinese export license is required. Essentially any dual-use or military applications will likely be prohibited from export. Jordan Schneider and Lily Ottinger at ChinaTalk did a good podcast/transcript on it here.

Across history, every genuine shortage has eventually birthed its solution—through substitution, innovation, or reallocation.

The Longer-Term Impact (if it persists)

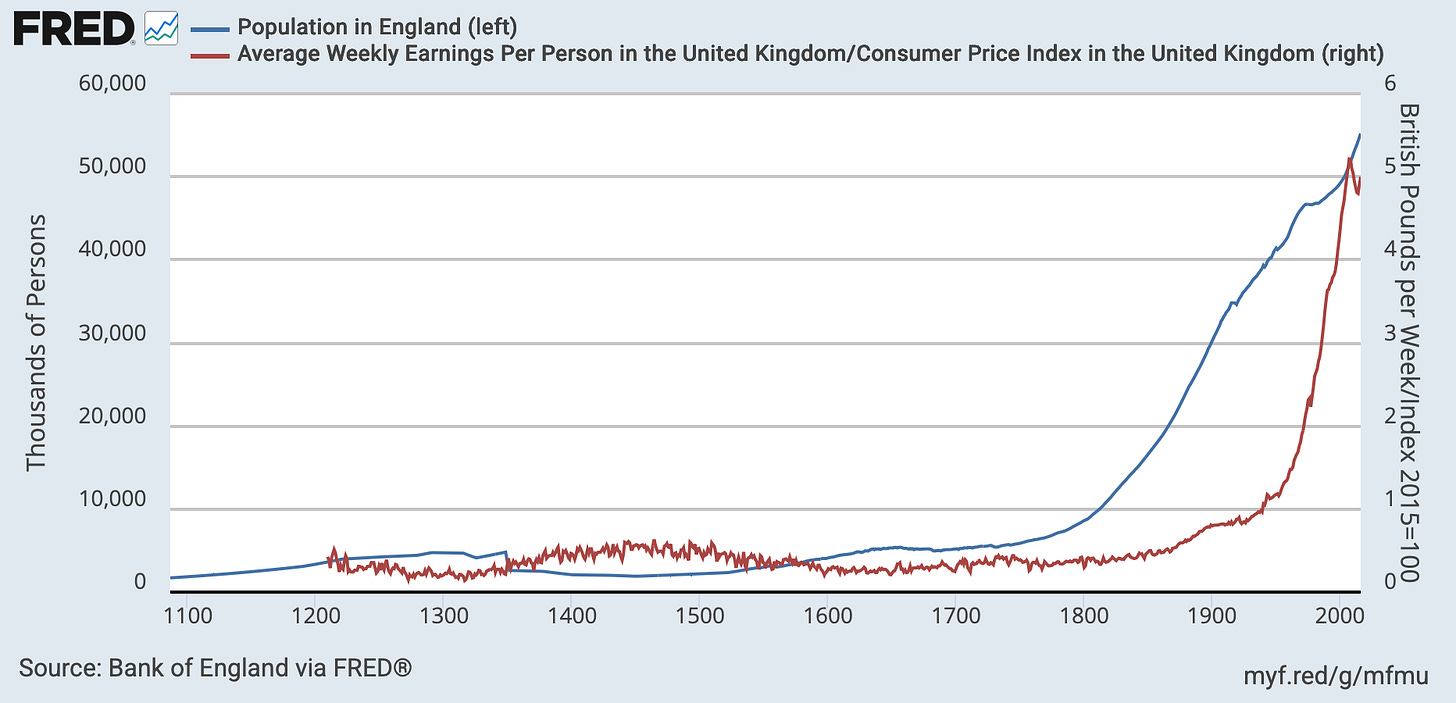

Most humans are terrible at predicting the future. The reason is only partly because we aren’t good at extrapolating curves—though we do have trouble understanding exponentials; see the parable of the king, the inventor of chess, and grains of rice.

The deeper flaw is that we assume the world's state is, more or less, fixed. This makes sense for an early hunter-gatherer on the African savannah. It does not in our complex, technologically driven modern world.

Thomas Malthus predicted in 1800 that the world's population would soon hit a wall, as our exponential population growth would outpace our linear ability to feed it.

That was, famously, quite wrong.

His observations and data were broadly correct. Why was he wrong? The answer is technology. The Industrial and Green Revolutions dramatically increased our ability to produce both goods and food for over eight billion people today.

The Framework for How it Always Works

A resource becomes scarce. The price skyrockets. And that price signal causes a few things.

It begins by restricting demand, as the price gets high

Then, new sources of the resource come online (made viable by higher prices)

Finally, substitutes emerge or technology develops to create new supply

In the 1800s, whale oil prices skyrocketed as whale populations collapsed and demand for oil lamps continued to rise. By the mid-century, kerosene and petroleum were developed and largely substituted—causing the volume of whale oil utilized to collapse.

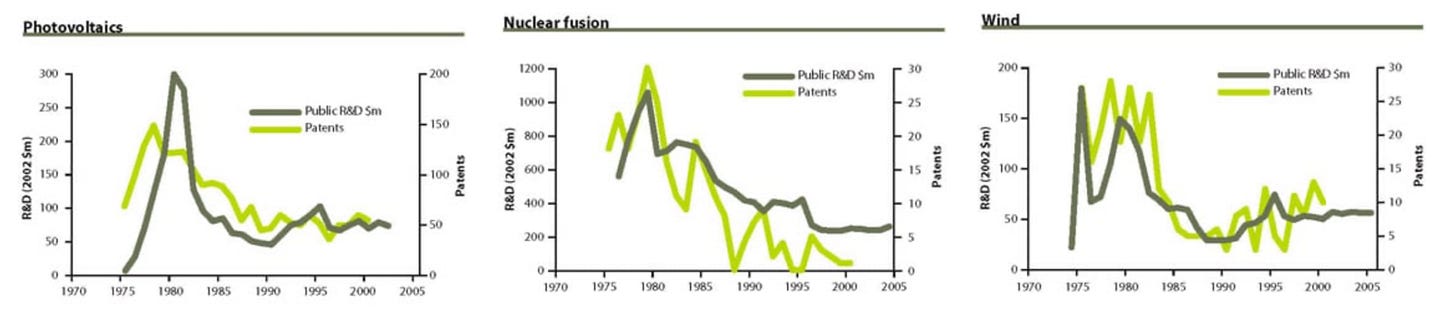

In the 1970s, OPEC oil embargo caused soaring oil prices. This helped spur on development of alternate, renewable energy—leading eventually to the capable clean solar and wind technologies we have today (the technological substitute). But we also have technological alternate supply.

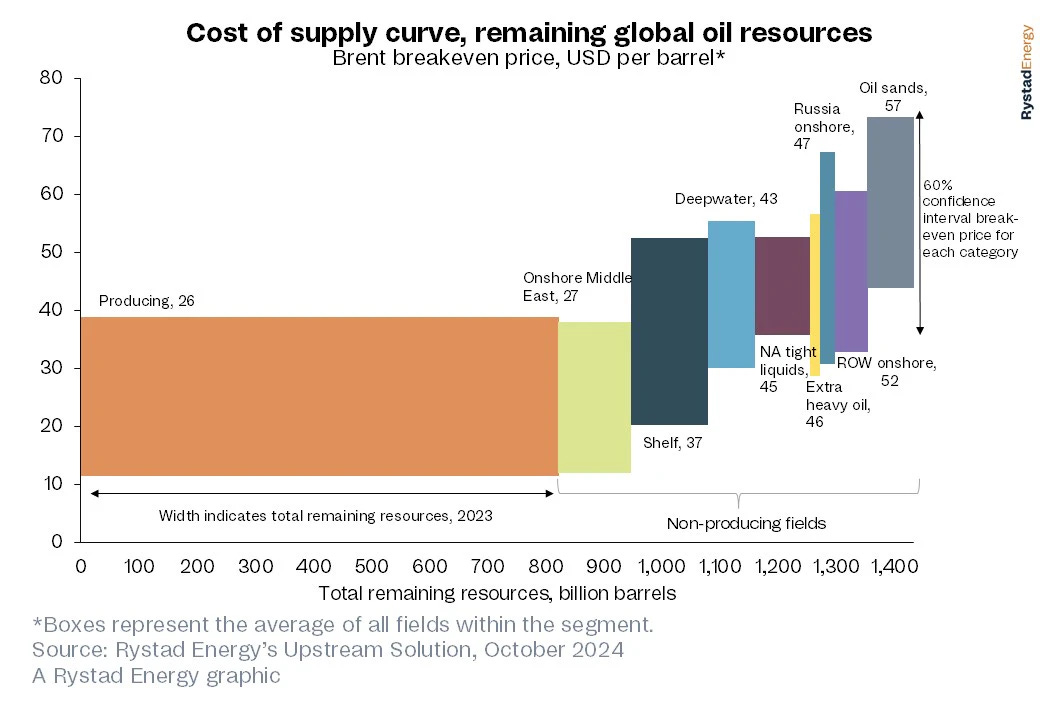

The ability of more fields to come online from currently non-economical sources constrains high oil prices. Shale oil sands in Canada, for example, are a well-known resource close to the US, and there are many such sources available. Even if the Middle East erupts once more, it doesn't necessarily mean that oil prices will surge indefinitely.

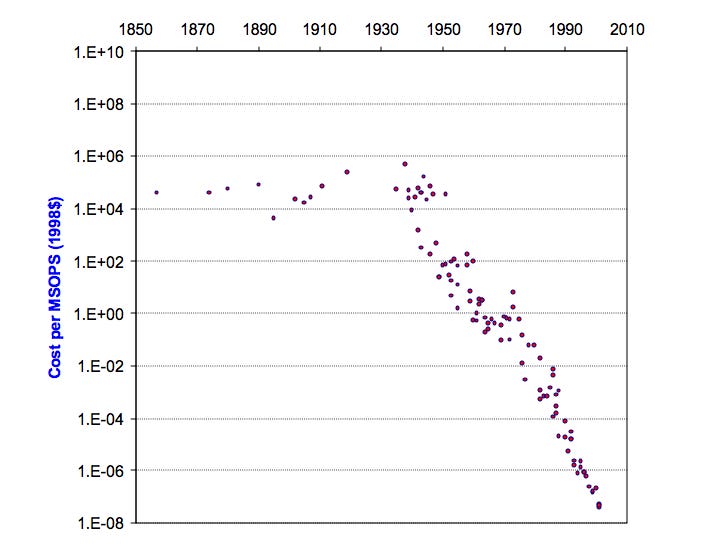

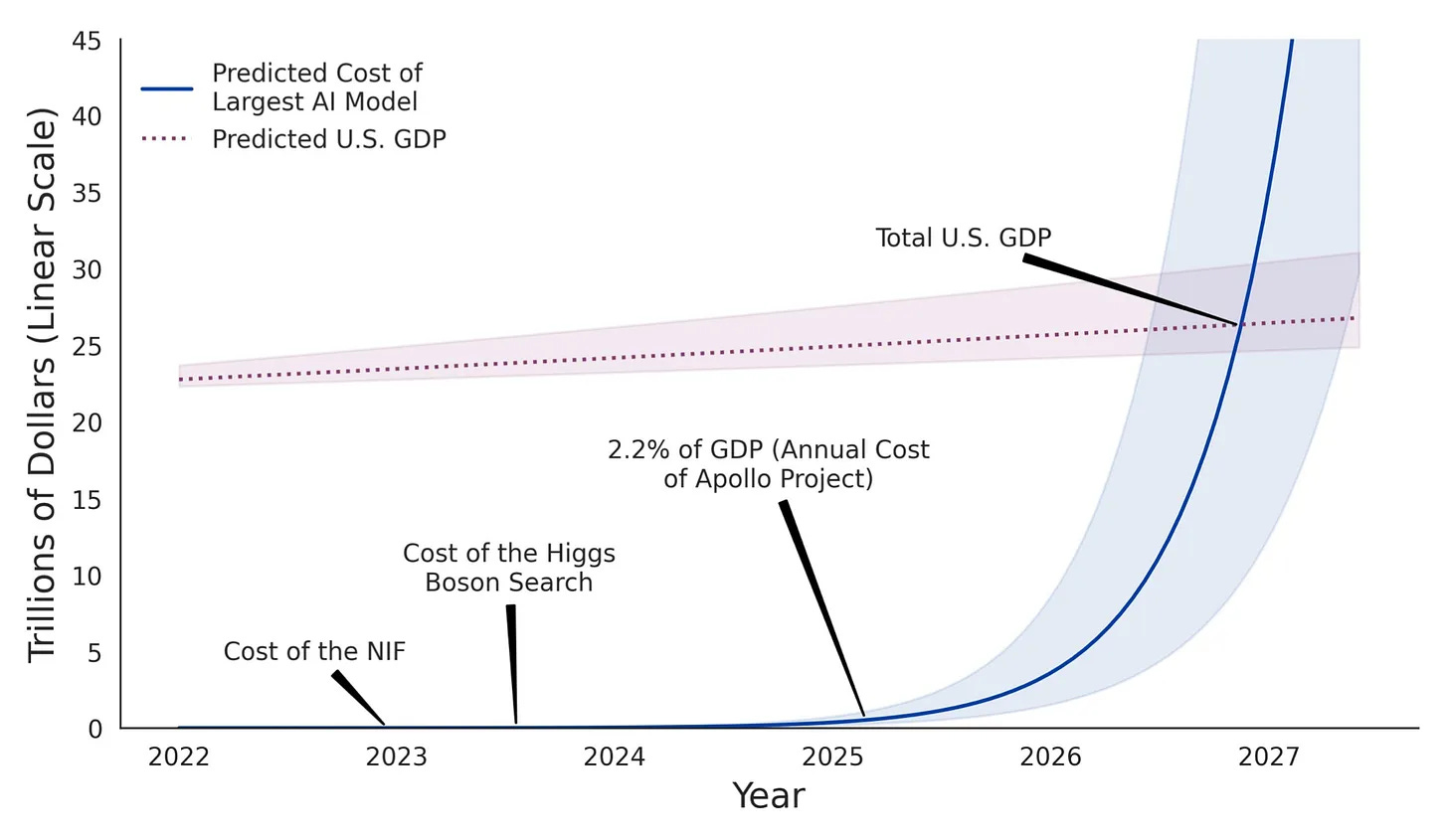

The same dynamic plays out in the digital world. Compute, too, behaves like a scarce resource whose cost drives innovation. As such, we will not, in fact, devote all of the world’s GDP to running AI.

Compute has always come down in cost, but especially as the AI boom (eventually) leaves its wild “just-dump-money-in” phase, we will find more and more efficient ways of running AI. Inference costs have already been plummeting. And to bet against compute costs falling… well, if you did it historically, you’d have lost a lot of money.

These weren’t necessarily easy achievements. A lot of solar coming online was from massive Chinese buildout. Plummeting compute costs were in part due to incredible technical advances in semiconductor manufacturing—and multi-billion-dollar leading-edge fabs.

But with price signals from restricted supply and continued demand… the market and human ingenuity respond.

Chip and Rare Earth Controls

I’m on the opposite side of the chip export control debate from several smart people I’ve met IRL like Jordan Schneider and Bill Bishop (at least I know they aren’t online bots!). I also listen to their podcasts, so I regularly hear their dulcet voices making the arguments while picking up and dropping off my daughter from school.

While it does give me pause—and makes me think harder about it—I’m still fairly confident from a macro perspective that forcing Nvidia/CUDA scarcity will create innovation in the Chinese ecosystem. Grace Shao continues to do a great job covering the topic and adding depth/analysis to the broad “gestalt” I get from speaking to Chinese counterparts.

My more specific views on how US export chip controls are effectively reverse industrial policy are here.

Note: Also, to be fair, the chip controls have effectively been so leaky that they hardly apply. I also think they likely wouldn’t totally disagree with what I would have thought was better policy if perfectly applied: complete chip non-restriction and total chip-making equipment restriction.

Which brings me to the note that helped spur me to write this piece:

I do actually think what’s good for the goose is good for the gander.

It’s extraordinarily painful in the short term if China squeezes on rare earths/critical minerals.

But I do think it’s ultimately doomed. They are required in too many products. If China fully cuts them off—which might not be true depending on how leaky theirs is—I can guarantee you that many products will immediately be facing redesigns (restricting demand). Yes, of course, many kinds of products will also get scarcer/get pricier.

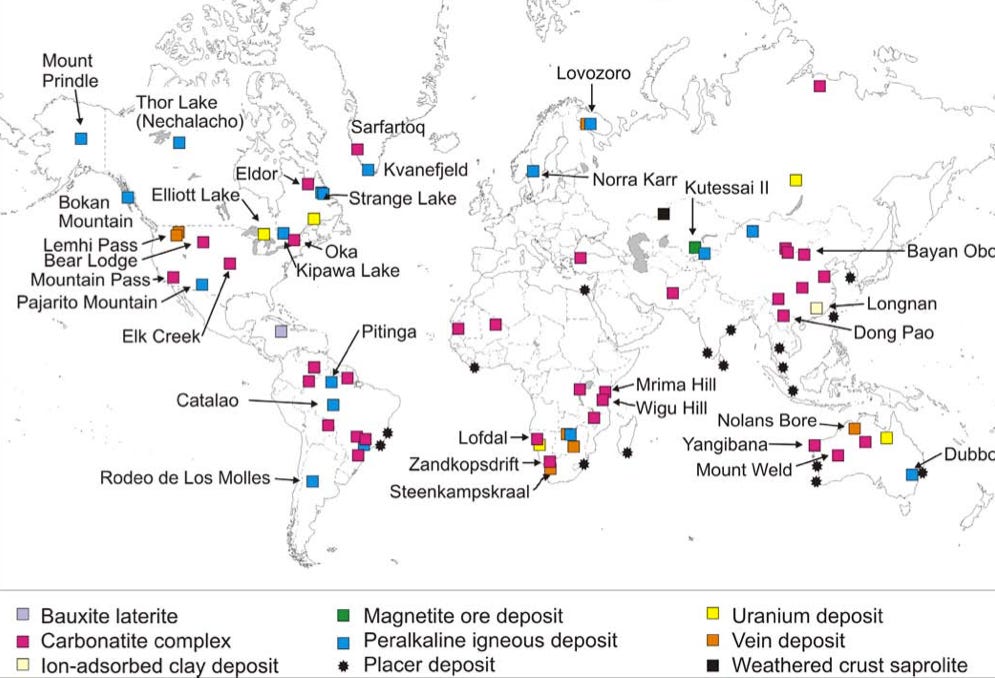

However, we’ll likely see more supply come online. Rare earths are not actually rare, and a lot of the difficulty comes from refining (as She said Xi Said covered well here). Of course, you can’t spin up a new mine overnight. Refining capacity is also still largely concentrated in China, despite all of the handwringing.

But that’s where technology comes in. I’ve watched/seen multiple deep tech startups operating in the rare earth/critical minerals space. I literally met a promising new one last Wednesday. A lot of these companies have failed to gain much traction while facing the existing, scaled industrial capacity of this commodity industry.

That obviously changes if costs skyrocket and real shortages appear.

I was literally talking to Devansh yesterday, who was wondering why a mining startup he saw at a pitch event during San Francisco Tech Week was so popular. This is, at least in part, why—and I expect all of these startups will likely be fielding a lot more investor calls if this continues.

In the short term, restrictions and shortages are painful. In the medium term, human ingenuity finds a way. And in the long term, those shortages are the seedbed of opportunity for new technologies.

Thanks for reading!

I hope you enjoyed this article. If you’d like to learn more about AI’s past, present, and future in an easy to understand way, I’m working on a book titled What You Need to Know About AI that will be published October 15th.

You can learn more about it and pre-order on Amazon, Barnes and Noble, or Bookshop (indie booksellers).

I agree with you “I’m still fairly confident from a macro perspective that forcing Nvidia/CUDA scarcity will create innovation in the Chinese ecosystem”

Your point about Canadian oil sands as alternate supply is particularly relevant today. Suncor Energy exemplifies the exact framework you describe - they've spent the last decade optimizing their operations to lower breakevan points from $80/barrel to under $30/barrel through technology and process improvements, not new megaprojects. The scarcity of conventional oil and high prices drove innovation in extraction techniques (SAGD, mining efficiency, partial upgrading) that made these resources economically viable. Now with geopolitical tensions rising, these long-duration assets with 40+ year reserves represent the kind of alternate supply that constrains energy price spikes. The same market dynamics that brought solar online during the 1970s oil embargo are now validating oil sands as strategic infrastructure.