The US Should Run Faster on AI Instead of Trying to Trip Up China

Export Controls and Trump's New AI Action Plan

Once upon a time, there was a small trading company in Korea that specialized in dried fish and noodles. It was called Samsung. In the decades between 1960 and 1990, the Korean government pushed this company into electronics and semiconductors.

Having no expertise in these areas, the company produced terrible products. However, the government protected it—setting tariffs on foreign competition and “encouraging” Korean businesses to use their terrible products. Critically, Korea did allow exported products to use superior foreign chips. They foisted the terrible Samsung chips onto the domestic market, which didn’t have any other choice.

Today, Samsung is obviously a global leader in electronics—and one of the two leading-edge semiconductor fabs. Notably, the other one is TSMC.

The former global leader and US champion, Intel, has in practice been out of the running—and recently said it may give up on ever regaining its place as a leading-edge semiconductor manufacturer.

The US’s Reverse Industrial Policy—Benefiting China

The recipe for building up globally competitive domestic capacity (replicated across Asia, including in Taiwan) is to restrict foreign competition, gain export competitiveness as quickly as possible, and force your uncompetitive product onto your domestic market.

It may suck for domestic consumers, but it gives your national champion the time, money (semi-captive customers), and experience (manufacturing learning curve) to become globally competitive.

Usually, this is imposed by the country trying to catch up.

Notably, the US’s chip export regime has done it for China. In a way, the US implemented policies that aimed to make Huawei and SMIC globally competitive in the semiconductor industry.

The ostensible reason for the controls was to cripple China’s AI progress. If that was the goal, it has been a failure.

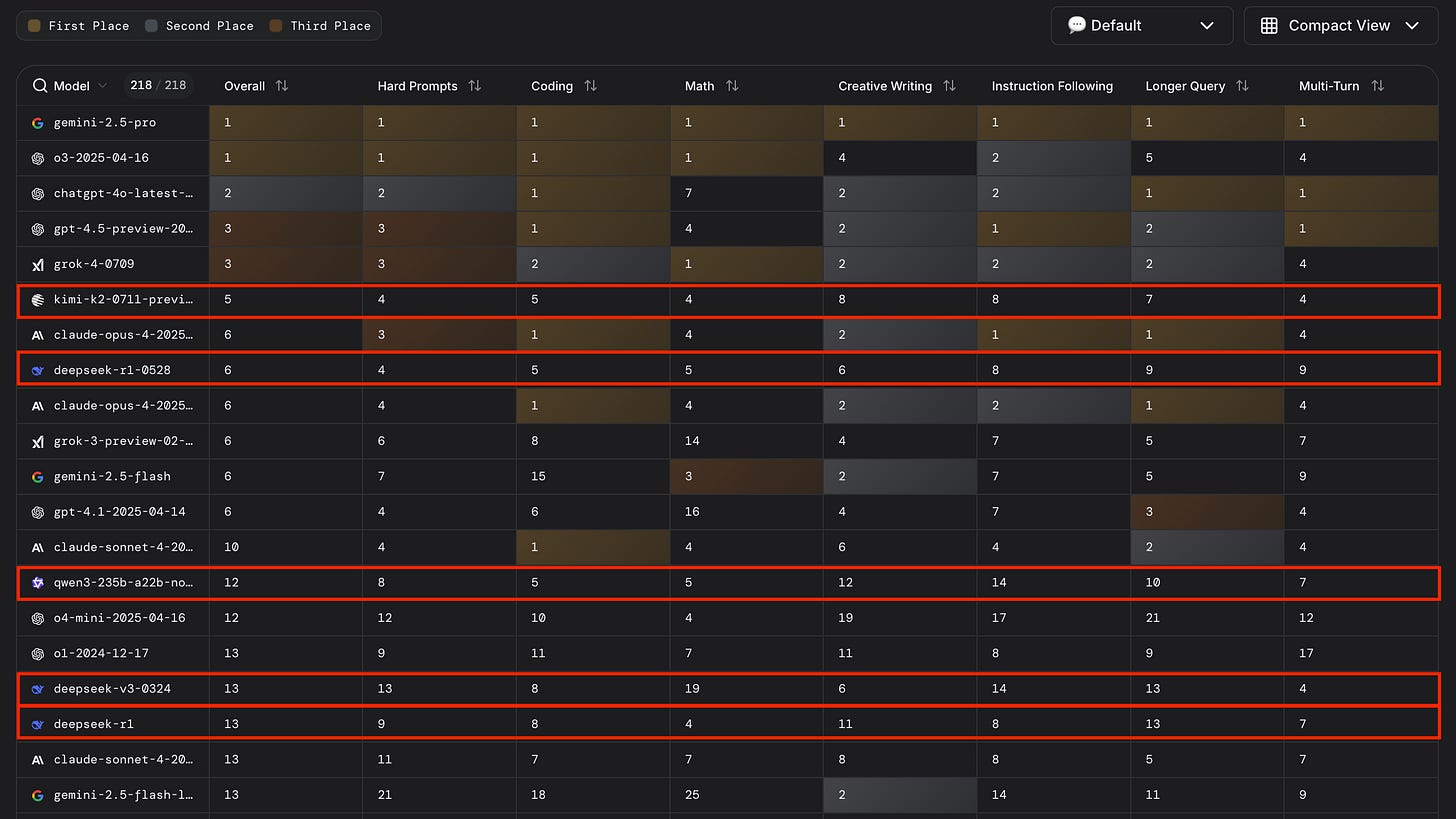

Just look at the many benchmark-leading Chinese models. DeepSeek dominated the news cycle earlier this year. More recently, Moonshot’s Kimi K2 became a frontier model that, similar to DeepSeek, is on par with the best American models and also cheaper.

On LMArena’s rankings, 25% of the models on its leaderboard are Chinese.

These models, notably, tend to be open-weight and very permissively licensed—which has encouraged many companies to use them as the basis for their own models.

What’s the problem? One problem is that, even without censorship from hosted versions of these models, they tend to skew towards the viewpoints favored by the Chinese government. They are likely post-trained to do so (or their datasets reflect it). As I was quoted in SCMP saying, it’s challenging to rip out those biases without impacting the underlying model.

Kids these days (and—let’s be real—most adults) already rely heavily on just asking models like ChatGPT for answers. Controlling the base model that everyone uses constitutes a significant form of information control.

This danger, among others, is the basis for efforts like Nathan Lambert’s laudable “American DeepSeek project.”

Trump’s AI Action Plan

Earlier this week, the Trump administration unveiled its AI Action Plan.

As for its goals, I’ll quote the White House’s own announcement:

Exporting American AI: The Commerce and State Departments will partner with industry to deliver secure, full-stack AI export packages – including hardware, models, software, applications, and standards – to America’s friends and allies around the world.

Promoting Rapid Buildout of Data Centers: Expediting and modernizing permits for data centers and semiconductor fabs, as well as creating new national initiatives to increase high-demand occupations like electricians and HVAC technicians.

Enabling Innovation and Adoption: Removing onerous Federal regulations that hinder AI development and deployment, and seek private sector input on rules to remove.

Upholding Free Speech in Frontier Models: Updating Federal procurement guidelines to ensure that the government only contracts with frontier large language model developers who ensure that their systems are objective and free from top-down ideological bias.

There’s a lot of choice language in the plan itself, like “Build, Baby, Build!” It definitely has many elements to it, but I’ll highlight what I found notable:

A weak form of the AI moratorium on state-level regulation that was removed from the Big Beautiful Bill. It relies on withholding funding from states and agency reviews—as such, it has a lot less legal force than congressional law. But it’s still an attempt.

Promotion of open-source AI and exporting it—and encouraging the government and the Department of Defense to adopt it. This is quite similar to a lot of Chinese efforts in both. It’s basically fast-following Chinese policy.

Lots of talk about building stuff (power, data centers, etc.). The agenda includes deregulation, encouraging workforce development, and trying to clear away barriers. I’m rather skeptical of this—but we’ll see if it amounts to anything.

Coordinate with allies and partners. Self-explanatory. Not really something that the Trump administration has made itself known for, so if this signals a change, it’d be welcome.

Miscellaneous: callouts for cybersecurity, tightening export controls in semiconductor manufacturing, biosecurity, and generating national datasets. This is a bit of a grab bag of miscellaneous stuff. The datasets effort, again, is a bit of a mirror to existing Chinese policy to cultivate and unify disparate datasets into “national datasets.” The “tightening export controls” aspect of this is focused on the right thing—semiconductor manufacturing systems and subsystems and not chips.

Combined with the Nvidia and rare earth deal, the US seems to be trying to directly compete with China, build more stuff, and not restrict chips (vs. semiconductor manufacturing). That all seems positive to me.

We Are Not in the Endgame

Harsh restrictions make sense when you think the technology today or in the near term will be highly impactful and at its apex.

Harsh restrictions do not make sense if the highest potential of the technology is still ahead of us. No export control is perfect. The longer the timeframe that is required to make these kinds of controls work, the less likely they’ll work at all. More likely, they’ll backfire—as they have in the US’s case, where Huawei has made significant progress and gained traction for their platform. Again, effectively the US has executed industrial policy benefiting the Chinese semiconductor industry.

Grace Shao covers Huawei’s modern capabilities well in an overview here.

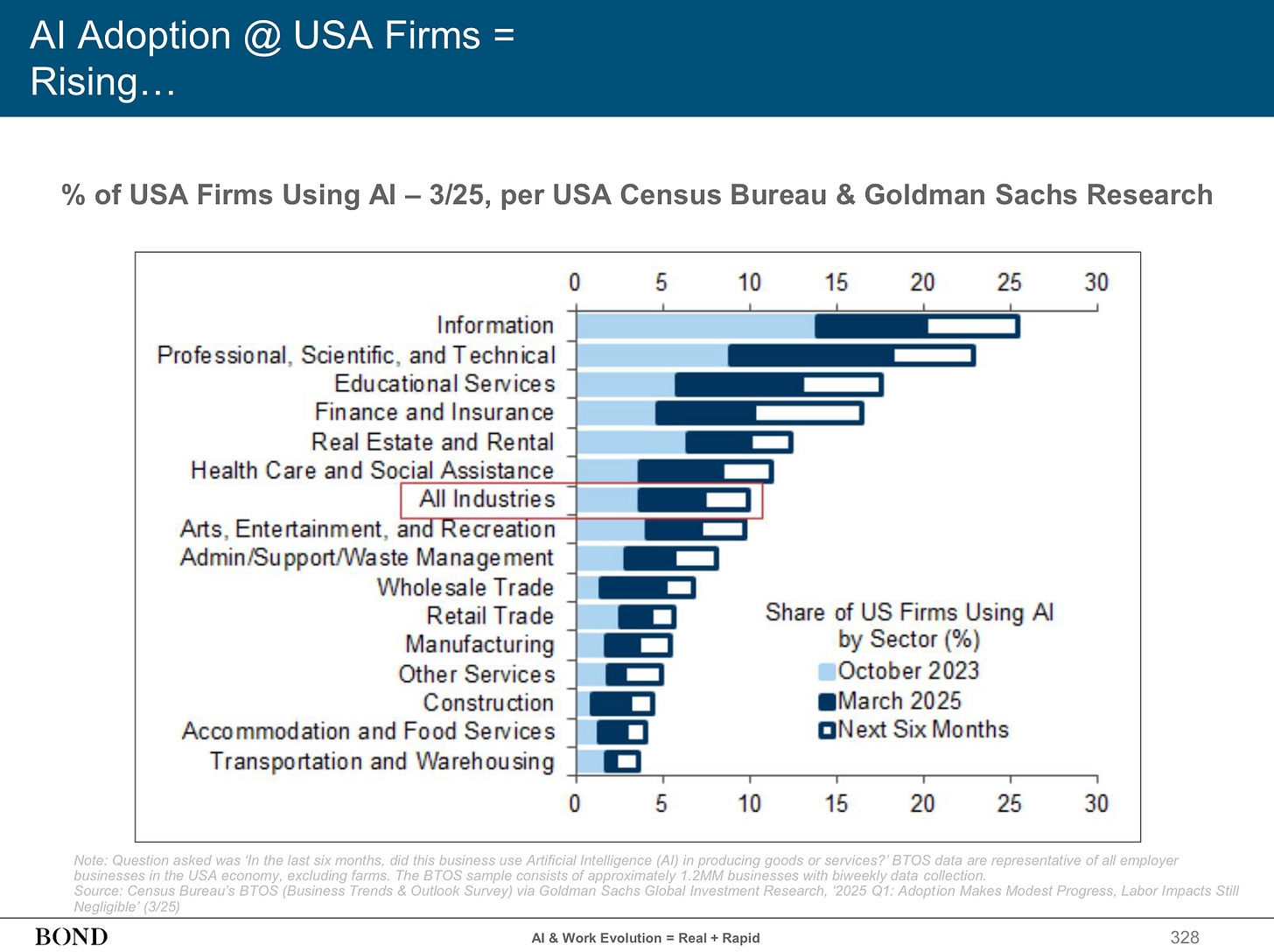

AI adoption is still in its early days, with Bond Capital’s presentation showing that adoption in all industries in the US was still less than 10% in March 2025.

Early internet commentators predicted that a plethora of blogs would dominate the world or create a decentralized utopia. It would have been unimaginable in the late 1990s that the world would get centralized into walled gardens like the social media platforms and have a single search engine be the “home page” of the internet.

That home page—Google, in case it wasn’t obvious—is now under threat by AI. Why go to Google when you can just “ChatGPT” it?

There are many different changes that had to happen to make Webvan a laughingstock of a business after the dot-com bust and Instacart a $13 billion business as of July 2025.

That included smartphones, better mobile connectivity, and more.

What will the future bring to AI? It’s still too early to say.

Given that, I think some of the current changes in policy—getting rid of the diffusion rule, easing restrictions around Nvidia chip sales, and trying to promote more development—make sense.

Hooked on CUDA

There are smart people I respect who think that chip controls are important. However, whether or not you think the PLA (Chinese military) will use Nvidia chips or not (which Jensen Huang denied… weirdly), isn’t it better for Nvidia, a US company, to be the global standard that gets sales/capital, feedback from developers, and the most progress on its platform? If you’re worried about leverage, isn’t it better to have everyone hooked on Nvidia’s CUDA platform instead of Huawei’s CANN?

I’ve talked about why CUDA is so sticky in the past, and that’s still true.

In that case, if conflict breaks out, you’d actually have something you can restrict that could cause short-term problems for China. Instead, currently, China possesses significant leverage due to its critical rare earth minerals, and we are still far from establishing non-Chinese refining and processing capacity to replace it.

While China itself definitely knows that it must diversify away from the US and build up both Huawei and SMIC, Chinese companies will use whatever works best. China has a famously competitive culture (just look at China’s “involution” problem). Being patriotic may mean using Huawei chips—but I suspect if Nvidia chips were freely available, they’d use those (and pay lip service to the Huawei clusters). After all, demand is still extremely high for Nvidia chips among Chinese companies.

Forcing these companies to use Huawei, providing sales/capital to them, and giving them market feedback and the capability to scale up their operations seems like exactly what the US would not want to do.

Thanks for reading!

I hope you enjoyed this article. If you’d like to learn more about AI’s past, present, and future in an easy to understand way, I’m working on a book titled What You Need to Know About AI that will be published October 15th.

You can learn more about it and pre-order on Amazon, Barnes and Noble, or Bookshop (indie booksellers).

It seems the US’s protectionist measures are having the opposite effect across multiple sectors, not just AI. We’re seeing a similar innovation surge in China’s EV, biotech, 5G/6G, and renewable energy industries in response to Western restrictions.

Ultimately, the AI race, like conventional kinetic conflicts, may come down to energy. China’s massive investments in power generation, from new nuclear plants to the mega-hydropower project in Tibet, underscore this. We’re certainly in for some interesting times.

I still think the best overall argument for open models investment is to increase the pace of progress and to make your engine of progress something that more groups can contribute to. Though, the loudest reason may be a real soft power component that will sway many companies away from adopting some standards regardless of ability.