Does DeepSeek Wiping out $1T of Market Value Make Sense?

No, but yes—a micro and macro view

I’m a bit tired of DeepSeek news, but the market is still down (as of this writing) and people are still asking questions, so I think it’s important to address whether it makes sense to wipe out that much market value from it. Especially since I’m better positioned from my background in both tech and hedge funds to more broadly comment.

DeepSeek released R1 on January 20, 2025. Of course, January 20 was Martin Luther King Jr. Day in the US, which is a market holiday, meaning that January 21, 2025, was the first day the market could (broadly) react. On that day, Nvidia started with a market capitalization of around $3.45B. As of January 31, 2025 (last Friday) was down by $14.74% and at $2.9B.

This means that market action—mainly due to DeepSeek, wiped off $500B from Nvidia’s stock, and $1T from big tech stocks generally.

Does this make any sense? Well, there are two different countervailing factors here.

Does the market action from DeepSeek specifically make sense?

Is the market price of tech stocks (like Nvidia, Broadcom, etc.) too high in general?

The answer to the first is no—in which the facts trying to support it are laughably easy to dismiss. The second is far more complicated—and one could very well argue yes—even now, post-DeepSeek.

Should DeepSeek have Nuked Nvidia?

Mostly, no. I’m focusing here on Nvidia because it has been the most central stock that contributed to most of the market value wipe-out, and also is the one most directly discussed.

The nonsensical argument that has been used to try to explain Nvidia’s price action is roughly as follows:

DeepSeek is Chinese, and thus uses Chinese chips, not Nvidia

DeepSeek is radically cheaper to train and use, which means we just don’t need that many chips anymore

DeepSeek means that the US is “washed” in AI, and China is ascendent in AI, and therefore US equities should suffer

To push back on the above, there has been a bunch of commentary on Jevon’s Paradox… which honestly is not a paradox. It’s just the normal, economic fact that “when stuff is cheaper, people buy more of it.”

No offense, but this is a dumb explanation to push back. Why? Well, all ordinary economic goods with elastic demand behave this way. As such, it’s not informative for specifically this case.

It’s also a bit dumb because AI is currently massively subsidized. If we think that cheaper AI means everyone is going to go crazy consuming it, numerous providers are already providing it for free or almost free (e.g., Sam Altman has mentioned that OpenAI’s losing money on their $200/month subscriptions).

Finally, it misses the crucial fact that all of those enumerated points about DeepSeek are wrong.

DeepSeek Uses Nvidia’s Technology

The first is easy to deal with. DeepSeek—self-reported—access to 10,000 A100 Nvidia GPUs. They also had access to H800s (the “nerfed” version of Nvidia’s H100s, modified for Chinese export). While they didn’t have the top-of-the-line, DeepSeek wasn’t exactly a “home lab” with access to a couple of consumer-level GPUs.

Beyond that, it’s important to note that these are Nvidia GPUs still. One of my most popular articles explains why it really sucks to program for AI applications on anything apart from Nvidia and CUDA. The funny thing here is that DeepSeek did extensively use something besides CUDA, which is how they achieved such impressive price-to-performance.

Specifically, they used PTX… which is a low-level instruction set used for CUDA. So yes, they extensively wrote low-level code for their work—in a format that is still locked into Nvidia.

DeepSeek (and everyone else) Still Needs Compute

The second claim deeply misunderstands how AI development works. I’ve repeatedly emphasized here that compute is overrated as AI’s bottleneck,and AI scaling isn’t really just about throwing more compute power at problems.

But don’t take my word for it, take Ilya Sutskever’s, former chief scientist and co-founder of OpenAI:

This is reflected in brass-tack explanations by, say, Logan Thorneloe on Society’s Backend with his pinned article on “What Makes Machine Learning so Hard for Software Engineers.” Specifically, it’s because AI/ML is much more probabilistic—which reflects the entire thing about experiments that Ilya emphasizes.

This, in turn, makes it clear why DeepSeek’s $5.5mm figure is not indicative of the cost of V3 (which, by the way, is usually what is cited and munged with R1). Specifically, as Nathan Lambert explains, that’s just the final run—and if you compare apples-to-apples, DeepSeek’s cost is still cheaper, but within the ballpark of other frontier models. The real cost is in salaries and experiments, none of which are included in the final run figure. And to be fair to DeepSeek, they openly disclosed that, but media reports ran wild with the low figure.

Finally, if you don’t believe any of this, believe Liang Wenfeng, DeepSeek’s CEO, who stated in an interview (translated here on ChinaTalk):

Liang Wenfeng: We do not have financing plans in the short term. Money has never been the problem for us; bans on shipments of advanced chips are the problem.

He obviously doesn’t think that “we don’t need many chips anymore.”

China is ascendant and the US is washed

Before this DeepSeek media and market craze happened, I called out in my 2024 GenAI in Review for AI Supremacy that “The Rise of Chinese Models”—and DeepSeek in particular—was one of the “big things” to pay attention to. I am not a China AI naysayer who religiously believes that US AI is just better.

That being said, I’ve pretty consistently stated that everyone outside the big US tech companies—including OpenAI—is an underdog in the AI race (which I addressed… again… in Who’s Winning the AI War: 2025 (DeepSeek?) Edition).

This is such a “vibes” argument that I don’t really have too much to add here beyond my piece linked above, especially since I want to move on to a more interesting discussion.

US Equities are Very Expensive—Even Now

Now, while “does DeepSeek wiping out the value make sense” is easy to address, it’s a much harder question whether stock prices of US equities—and especially the tech stocks—make much sense.

The reason is US equities are expensive, even after the DeepSeek drop, by almost any metric.

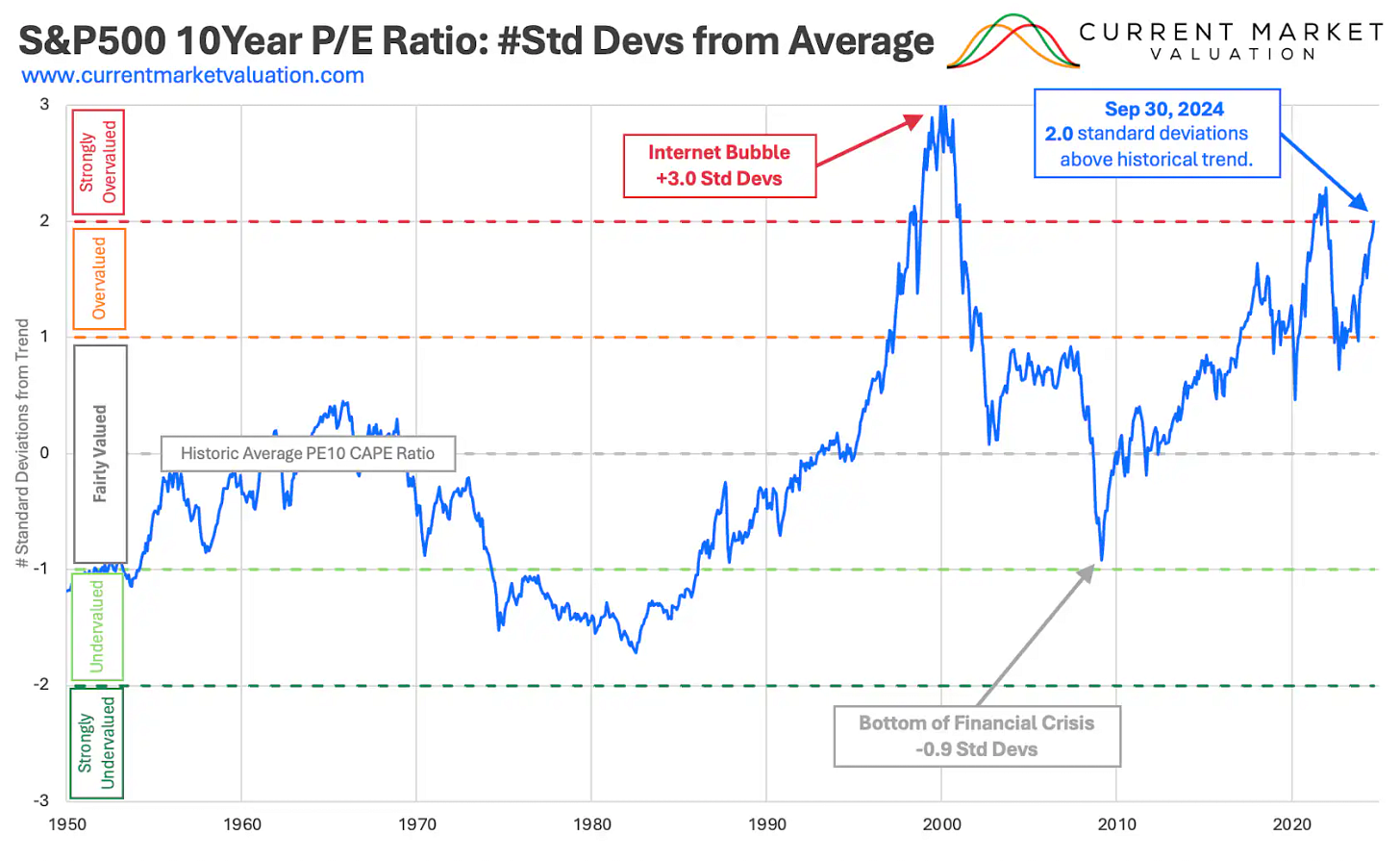

P/E ratios are historically VERY high

One fairly fundamental metric is the P/E ratio, which measures how expensive stocks are relative to their (historical) earnings. In this case, we’re using a version that is averaged over 10 years to remove some cyclical fluctuations. You can get the exact definition here, but that’s the broad idea.

It’s a backward-looking metric—and far from perfect—but it’s also smoothed out with the longer historical picture.

As you can see above, it’s extremely high (and only got higher since the measurement date) relative to history—and also is unique to the US, since everyone else looks more normal.

Of course, P/E ratios will not be “locked into place.” There are multiple reasons why they’d move around.

Interest rates and P/E ratios

One simple one is interest rates—if you make less money from simply saving in a bank account (or treasury bond), you’ll be more willing to pay more for the same “unit” of earnings. Inversely, you’d be less willing to pay up if you could just buy a bond or keep it in a deposit account.

The thing is—interest rates are fairly high relative to our recent history of zero rates. Additionally, we’ve gone through significant interest rate cycles, and you don’t see those P/E ratios highly correlated (over the longer term) with interest rate levels. In a shorter-term perspective, especially during the inflation of the 1970s and early 1980s, it’s inversely correlated.

Growth and P/E ratios

The second is growth because this metric is backward-looking. You might expect that the next 10 years of growth in earnings will be massive, relative to the last 10. This, of course, is the most likely reason one would argue that today’s metrics (just like the DotCom bubble) are reasonable.

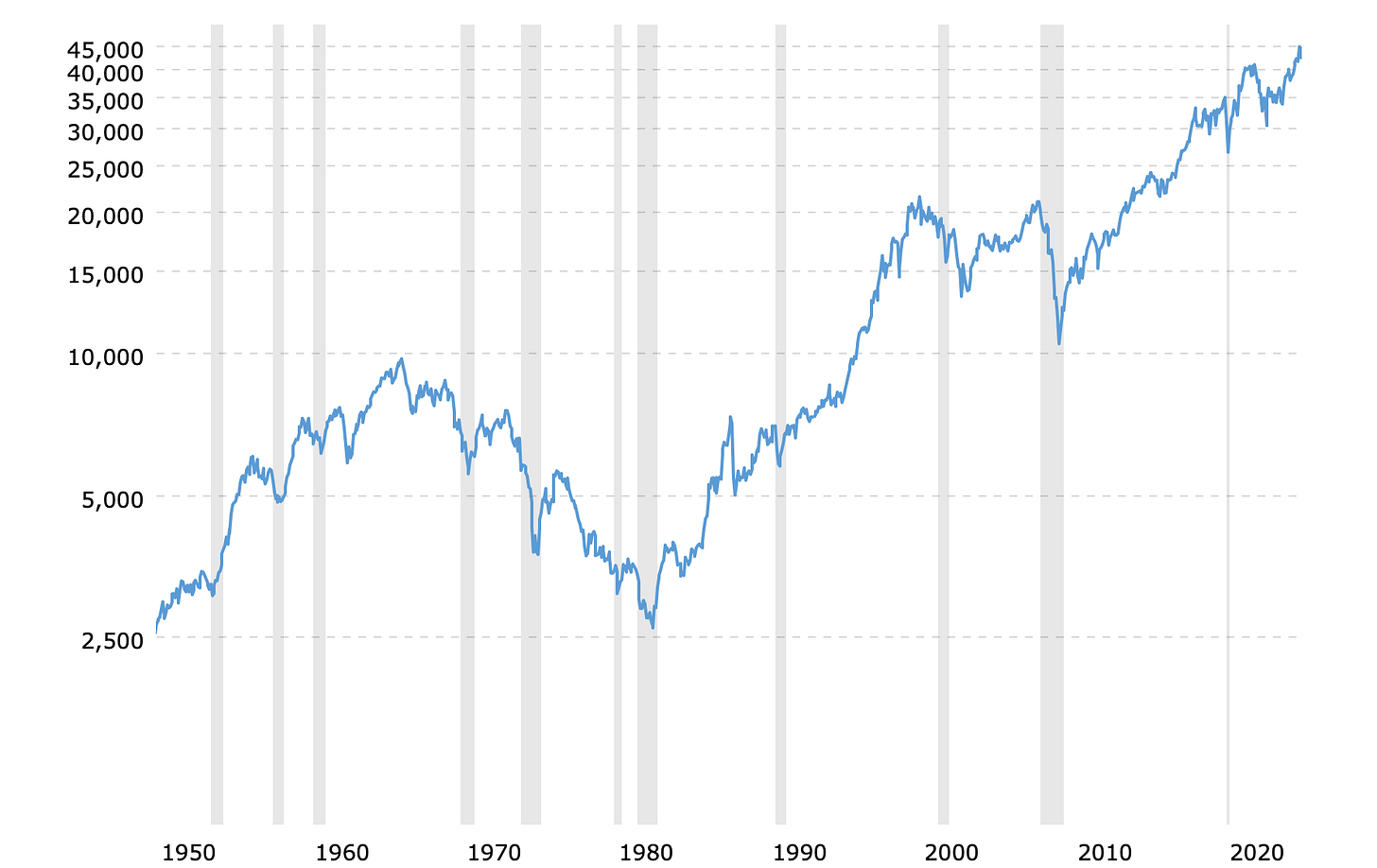

Of course, the US after WWII in the 1950s onward—where it became one of two global superpowers (and, in hindsight, the main one with all of its intact industry, science, and massive resources after the World Wars)—was no slouch in the growth department.

Putting it together

Combine the two, and you can understand post-1950s stock performance, where you had strong performance—but then stock markets got crushed by inflation and interest rate spikes in the 1980s (Volcker) in particular.

All this is to say—it’s fairly predictable how you would get P/E ratios and stock performance, and it’s very elevated right now. You can’t explain it by interest rates, and you’d have to believe something very fundamentally different about growth going forward.

Maybe it’s true, but do note that the DotCom Bubble’s “this time is different” was also wrong—and Google and Amazon becoming titans after the bust did not look insane from a P/E ratio perspective because by that time, their “E” was very high, even if “P” was too.

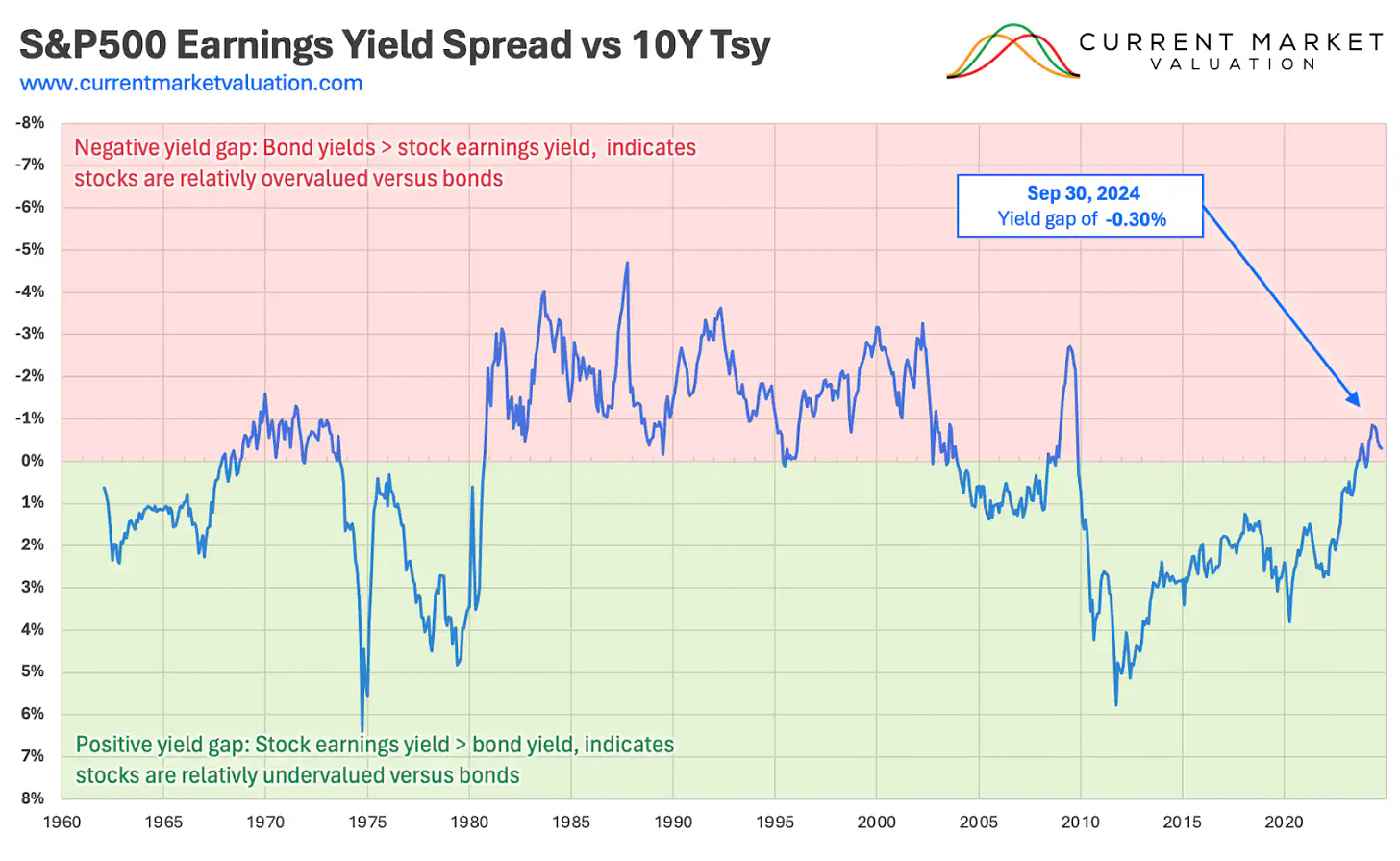

Another Lens: Earnings Yield Spreads are Negative

As said above, one of the reasons why P/E ratio moves around is because of interest rates. This is because you will trade off between stocks and (for better apples-to-apples) long-duration (10yr+) bonds. We already talked a bit about how this worked in the 1980s especially, where interest rates spiked and made US stocks very unattractive relative to fixed-rate instruments like bonds.

The earnings yield spread (vs. 10-year treasuries) is one way to see this. It’s a different lens on the P/E ratio (it’s essentially the inverse), where we use that to compare the relative attractiveness of stocks vs. bonds.

We can see the 1980s, where it’s understandable why stocks nosedived going into that decade. However, they did perform well after the peak in the early 1980s—because interest rates kept going down after the peak in the 1980s. This means that even if stocks stayed “just as unattractive” from an earnings yield spread perspective, their prices went up as interest rates came down. That’s the reason the spread stayed the same.

That’s all to say that this mechanism does have understandable characteristics and is another useful lens for pricing stocks (even if it isn’t completely independent of P/E).

In the post-2008 period, what drove attractive earnings yield spreads was the fact that interest rates basically hit zero and had a lot of trouble rising. That changed more recently, with interest rates finally moving up again… and stocks also rising and not becoming more attractive.

As we can see, for the first time in nearly a decade and a half, earnings yield spreads are negative. Not surprising: interest rates went up… and stock prices also shot up.

What’s the synthesis?

Any experienced investor will tell you, from personal experience, that valuing financial assets is hard. Even if DeepSeek doesn’t spell doom for US tech stocks… perhaps it’s merely the catalyst for a correction to elevated US equity prices. As said, one reason that you could argue that “this time is different” is because of AI itself.

The problem, of course, is that all the times that were different… weren’t. Even the DotCom Bubble wasn’t different because even though we got Google and Amazon afterward, they were reasonable in P/E ratios and expected growth given what they became by that era.

After all, an even longer-term perspective on PE makes this obvious. The three spikes are: the Roaring 20s (and the end of it being the Great Depression), the DotCom Bubble… and now.

As such, I do think that DeepSeek is an overreaction… but that US equities are also quite overvalued.1 Where it’ll come out in the longer term is a question, but knowing what market action is “right” is not as simple as analyzing the technology itself.

Thanks for reading!

I hope you enjoyed this article. If you’d like to learn more about AI’s past, present, and future in an easy to understand way, I’m working on a book titled What You Need to Know About AI that will be published in 2025.

Sign up below to get updates on the book development and release here!

That being said, I did buy a bunch of the different stocks expecting that we’d get a short-term rebound—which we did.

This is an excellent read! And thanks for linking my article. I'll also add that Trump's tariffs (or planned tariffs) probably had quite a bit to do with the crash as well.

Clearly argued, cutting through current jargon around the issue James, thank you.