Why we need AI as a society

We’re aging too fast (AKA my entire AI/robotics investment thesis)

Attention on certain topics comes in waves. Recently, there’s been more attention on the entire world having fewer children. I came across a few podcasts wrestling with it and asking, “Should we have more kids?”

There are many failed programs around the world, like in Korea, to boost fertility rate that have led instead to woman-blaming. And, in counter, articles over the years about how much it sucks being a married woman in Japan (though it applies to Korea as well)—enough so that plenty of young women are opting out entirely.

Of course, this does not apply in the notably egalitarian Nordic countries, where they’ve encountered the same thing.

In general, higher incomes mostly correlate to lower fertility. This seems like a natural outcome of shifting societies and also lower infant mortality, but no one really has a definitive answer.

Of course, the thing here is even “developing” countries like those in Southeast Asia (and, famously, however you classify it, China) are hitting the same wall. African (and Central Asia to a lesser extent) is pretty much the only place in the world with booming population growth.

As a natural result, the entire world will age rapidly in the coming decades.

Ok, so what?

Some of those podcasts I referred to at the beginning struggled with the “so what,” question. A few took the perspective of the Degrowth movement that it’s a good thing, and we are running out of space/resources. I linked Noah Smith, who is notably hostile to the idea, but he also gives a good summary of it.

Myself? From a moral perspective, people can feel as they want, but the attempted “scientific” or quantitative arguments behind it are too Malthusian (after Thomas Malthus, who, between 1798 and 1926 argued that the world was about to hit a population crisis and collapse). I keep talking about how bad people are at understanding exponential curves and changes that come from it, though usually in the context of compute. Nonetheless, with things like Peak Oil theory where we should have run out of oil in the 1970s (and then every decade after that), or the most catastrophic predictions from An Inconvenient Truth in 2006 being averted through rapid cheapening of renewable sources… people tend to think in terms of “all else equal” and things generally aren’t.

Now, that applies to what I’m about to discuss as well—and where AI and AI combined with robotics, in particular, come in.

The entire world’s population shrinking is not necessarily a bad thing. The problem lies in the world’s population aging.

Fewer young people relative to old people, in crude terms, means less manual labor to throw at problems to sustain society, relative to the total size of society. More old people who need to be served or need things made by manual labor, fewer young people to provide it.

This is definitely true in the US, even though it’s actually less severe than in other countries (immigration has kept the country younger). This ratio, called the dependency ratio, is skyrocketing in a bad direction.

This means something simple: you either make do with less (because we can’t make as much, have as many services, etc.) or you need to massively boost productivity.

So: massively decrease standards of living, or massively increase productivity.

The latter is the only way to avoid the certainty of the latter.

In general, as per the history of economic contractions (most notably, the Weimar Republic in Germany becoming, famously, Nazi Germany—but also over and over again in South America and Middle East), people don’t take falling living standards well. At all.

It’s nice to say, from a comfortable, developed country with a lot of income, “I could do with minimalism or do more with less”—for a lot of the people not in such comfortable situations, that viewpoint can quickly become either morally repugnant, or more to the point, a cause for unrest and violence.

So, why hasn’t this been a problem?

It actually has been. It’s one of the main investment pillars for Creative Ventures—labor is becoming scarcer (which makes many things harder) and health care costs keep going up for countries all around the world. I’ve talked about it for years, including on various podcasts.

I’ll focus on the US because I know the ins-and-outs of it (having watched these data and trends for over a decade now) and it has easily accessible/reliable data. However, this applies to basically all the regions I’ve mentioned to some degree or another.

It hasn’t been catastrophic because productivity has increased too—it hasn’t quite kept pace, but it has gone up. But this isn’t the whole story, or even the most important one.

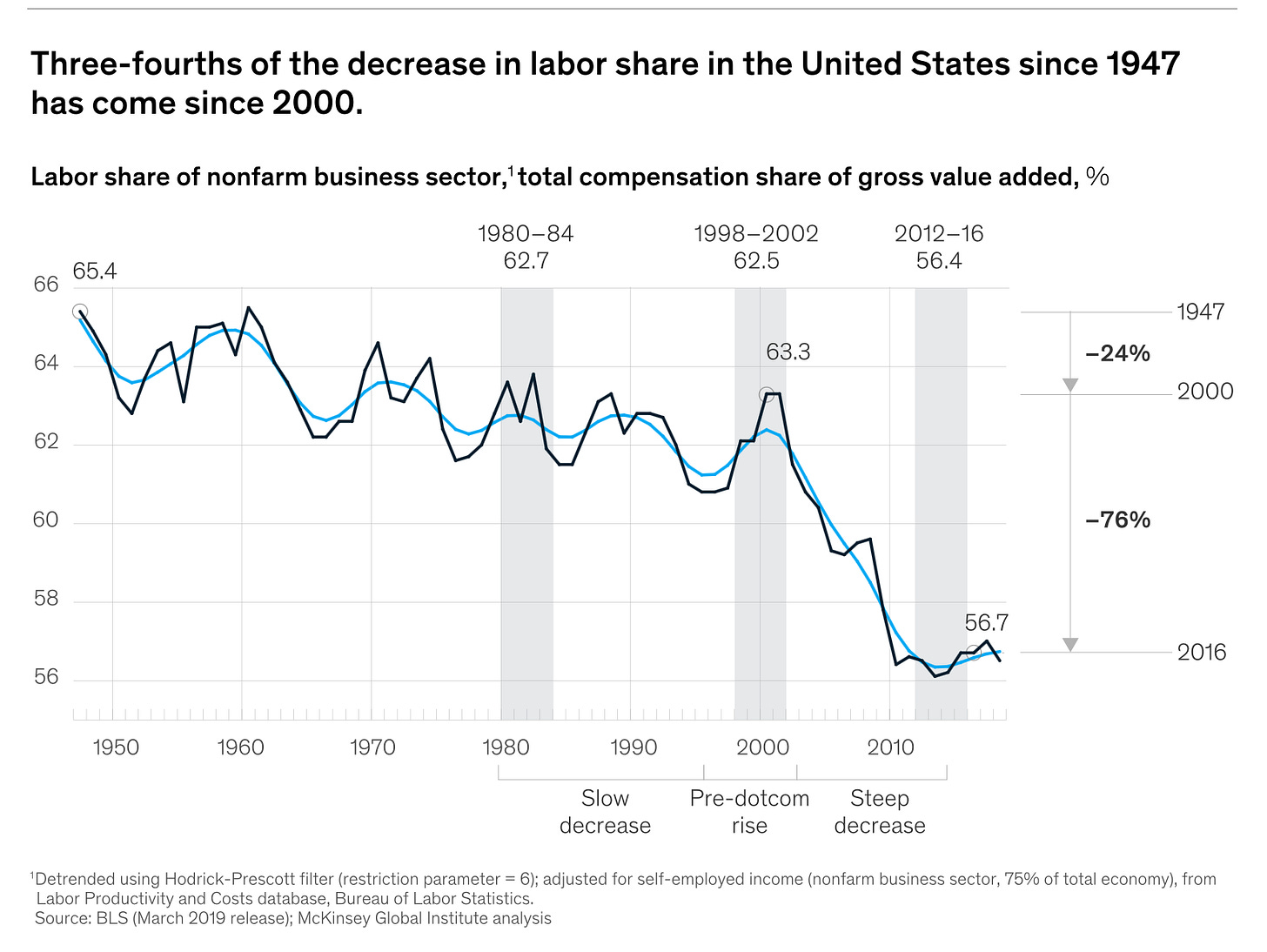

That’s prevented worsening standards of living, but it hasn’t generated the kind of boom that we saw in the 1950s-1970s in the US. Worse than that, we have seen a contraction of a sort—specifically in labor’s share of the pie in GDP (meaning, production / share of income).

It’s complicated why this is true. If you were to take the most naive view, we should see less supply of labor with increased (relative) demand push up wages. In fact, we have seen that especially recently. However, that’s not the only way you can try to solve a labor problem.

You could just wholesale get rid of the need for it within your country. Fortunately, there was a huge, cheap labor force that came online in the 1990s-2000s. And that’s the real story that explains both, and happened at the same time the dependency ratio skyrocketed.

China.

The simple argument of the free traders, and the classic Ricardian Model that I grew up with as a young ‘90s kid, was that trade was optimal given a perfectly efficient system and made everyone better off. Models, of course, have been known to fail. They aren’t bad, but one should realize they are an oversimplification of reality—one that hopefully gives you useful insights, but you shouldn’t base everything on.

In reality, getting rid of your industrial base really does do things besides just make everyone richer. One is that you need less of a base of labor, and you tend to specialize into certain services industries (including financial services—which is basically all the UK is, for example), and high technology (which has saved the US from being like the UK).

While the US still has strong technology companies (obviously—just look at NVIDIA, Microsoft, Apple, and the like), this doesn’t really give a nice pathway to a better life and wealth for the vast majority of people. As such, we’ve also seen income divergences sharpen over this period and economic inequality grow.

A lot of this pathway got given to Chinese workers, which brought a billion people out of poverty. While that’s become something that’s infuriated portions of the US after the fact and has now become an issue with US-China competition, bringing people out of poverty and suffering is obviously not a bad thing.

The problem is that you can’t bring that kind of engine online with a counterparty with multiples of your population without having any equilibrium effect on your population. Economists of the classical mold would have said that all of those workers who would have been in manufacturing or more “labor-focused” jobs should have just all become high-tech or service workers that would have increased their wages even more. In reality, people aren’t quite that fungible, especially with no concerted effort to allow for that kind of retraining.

But this isn’t about China-bashing

I do talk quite a bit about US-China competition here, especially given my focus area in AI, but honestly the story here isn’t about “China bad” (and, in general, in terms of Chinese people vs. its governmental direction, it never is). That’s merely the explanation for why you haven’t seen global manual labor wages skyrocket over this period. We had a big one-time shock of essentially an isolated country with a massive poor labor pool suddenly join the global system.

A one-time windfall of money is not what you should base your budget on, and we don’t really have these kinds of labor pools lying around that will change our trajectory again in the same way.

China itself now has a demographic crisis on its hands too, thanks to the one-child policy. All of Xi Jinping’s declarations that women should be patriotic and have more children haven’t actually changed that trajectory.

This crisis that was averted for two decades thanks to China (and the Global Financial Crisis in 2008—but that’s a much more complicated story that usually takes much longer to explain) is now going to finally hit.

But real wages going up are good, right?

So, this means labor will be scarcer and will get pricier. After complaining about inequality and a lack of pathways to good wages in the US (which, regardless of your political affiliation, is part of having a happy, non-violent society, similar to the entire thing about living standards), and the like… what’s the problem?

Well, aside from the issue being global and not just about the US, the other issue is that on a macro level, we simply don’t have enough labor. Economic theory breaks down in extremes, and certain things we want simply won’t get produced because labor is too expensive to make it worth it.

That isn’t because of corporate greed in “not wanting to pay workers more,” but at some point, you’ll be ok not having some good or service you’re used to if the price skyrockets. If, for example, pizzas cost thousands of today’s dollars because of labor costs… well, I think most people—consumers, not businesses—would probably do without pizza rather than pay it.

That’s why AI/robotics is needed.

(For readers who aren’t familiar, one of my better known investments is a pizza robotics company. I mean, it is cool, but, after all the othercool stuff, you just invest in one pizza robotics company…)

Fewer workers do more stuff, not mass unemployment

The reason AI is not going to cause mass unemployment is because it’s a tool. My most used analogy is that you didn’t see mass unemployment of diggers when the shovel was invented and made it possible to dig much further.

Similarly, we haven’t had mass unemployment ever since farmers stopped being most of a country’s population. Far fewer farmers produce enough food for everyone. Thanks, Green Revolution.

The point of this is: technology (and tools generated from it) does not throw people out of work. More technology means more stuff with less labor—literally the definition of productivity. But the thing about productivity even though you require less labor to produce the same amount of stuff, that means a single laborer suddenly has much more economic output.

The demand for most things is not fixed. Cheaper stuff means more stuff is bought. But even if that isn’t the case (let’s say there is only so much pizza people can eat), more productive people means that those productive people go off to make more other stuff—similar to the agriculture example.

Unlike the China case, where it wasn’t productivity, just more people(thus surging supply of labor and depressing wages), technology boosts wages.

And this is why we need more labor automation

I’ve seen this in my investing in AI-driven robotics. And you can intuitively understand it, too.

Most sucky jobs have high turnover. Let’s stay on pizza. If you are the greedy pizza shop owner, you aren’t thrilled that your labor keeps turning over. But you want to actually have a profit, so you aren’t willing to pay workers that much more. Why? Well, people are already up in arms about fast food prices. You probably can’t charge more, and you never made that much margin anyway, so you can’t afford to pay more.

So, instead, you still have terrible margins, a giant headache of labor turning over, and many times you just can’t find people at all.

Well, what if we now gave this business a way to make each worker 10X more productive?

In theory, you might expect, “Wait, the business is now going to get rid of 9 workers.” In reality, the business was almost certainly understaffed to begin with—the pizza shop probably just has one tired worker hanging around to work the cash register, stick things in the oven, and interface with DoorDash drivers. During peak hours this worker would fall hopelessly behind, service would suck, and people would want to order less.

Staying in reality, let’s say this worker becomes 10X as productive with a lot more ease in the job. That means peak hours would suddenly become efficient, and the worker wouldn’t be stressed out as much, taking on what used to be three people’s jobs.

This would make the entire operation better and more profitable, but it also allows the worker to gain even more mastery to (usually) increase productivity even further with experience. This isn’t typically possible with just manual labor, but manual labor with specialized tools does have this characteristic. All of a sudden, the business can avoid just hiring a revolving door of countless shift workers (a bunch of whom don’t show up anyway, or soon quit) and would rather pay this one worker significantly more. This isn’t out of a “goodness of heart” from the greedy pizza shop owner. It’s because the business can now afford it, and it’s profit maximizing to have the more efficient worker.

The secret sauce of AI in robotics

Now, why did this not work before AI and robotics?

It did for numerous industries. After all, many types of manufacturing are highly automated. Agriculture, as said, is highly efficient now with very heavy automation (and other technologies) as well.

But many industries are very resistant to automation. Construction. Logistics. Food services.

If you talk to people in them, they’ll often cite that these are “conservative” industries that don’t like change. However, one part of that conservative-ness is that most of these industries have tried various technologies that have failed horribly. If everything you try doesn’t work, you would also get “conservative” about trying new things.

The reason these industries are “special” is variation.

No room in construction is ever truly square (meaning 90 degrees corners). People buy all sorts of random stuff from Amazon together in a single shipment. Every food service worker knows the random assortment of preferences, requests, allergies, and more that they get in a day.

Certain industries can be highly standardized and controlled. This leads to the ability to use “traditional” automation. Basically, you can throw mechanical engineering at the problem.

The industries that have tons of variation are not amenable to throwing mechanical engineering at the problem. You need machines that are much more flexible and adaptable. You require machines that exercise some form of intelligence. This is why these industries have people wielding tools (construction workers with power tools, pizza workers with specialized sauce spoodles).

Even if the work is not really that taxing to a human intelligence (i.e., it’s still brainless), that variation still forces the attachment of a vastly overpowered human intelligence to each tool.

This changes entirely if the tools themselves have some limited intelligence. They don’t entirely replace some higher level intelligence requirements (oversight, direction, etc.) but at least you don’t have to inefficiently attach a human to all of these tools constantly.

AI finally, for the first time, gives our tools that kind of limited intelligence that can handle minor variation. Not a lot of variation, mind you, which keeps humans quite firmly in the required category, but fewer of them doing brainless (for a human) jobs.

Driving, by the way, is in this category. Countless random things happen on the road. Kids wander into it, pedestrians don’t follow laws, random trash or obstacles get strewn into it, some unscheduled construction happens… the list goes on. This ultimately is what makes autonomous driving so difficult and still so prone to problems. Driverless cars in San Francisco were getting defeated by cones. Teslas seem to be unable to see fire trucks and certain other emergency vehicles.

It shows the application of a lot of AI to the problem—and clearly demonstrates the limits of how well it can handle variation.

However, it gets us closer, and finally unlocks that kind of 10X or 100X improvement in so many of these labor-heavy industries that were so resistant to automation because of variation.

And, for that reason, it will actually help workers in it. It makes their jobs less brainless, and increases the ability for them to get higher wages. And, in the midst of this, it’s the better fork of the trade-off of our demographics.

Remember: we either massively decrease living standards, or find some way to become massively more productive.

This is why we need AI to allow us to choose the path of becoming massively more productive.