Writing, Originality, and Why Does Anyone Care What I Write About?

Musings, Insecurities, and Thoughts on Writing a Book (or Substack)

The nature of self-promotion in writing

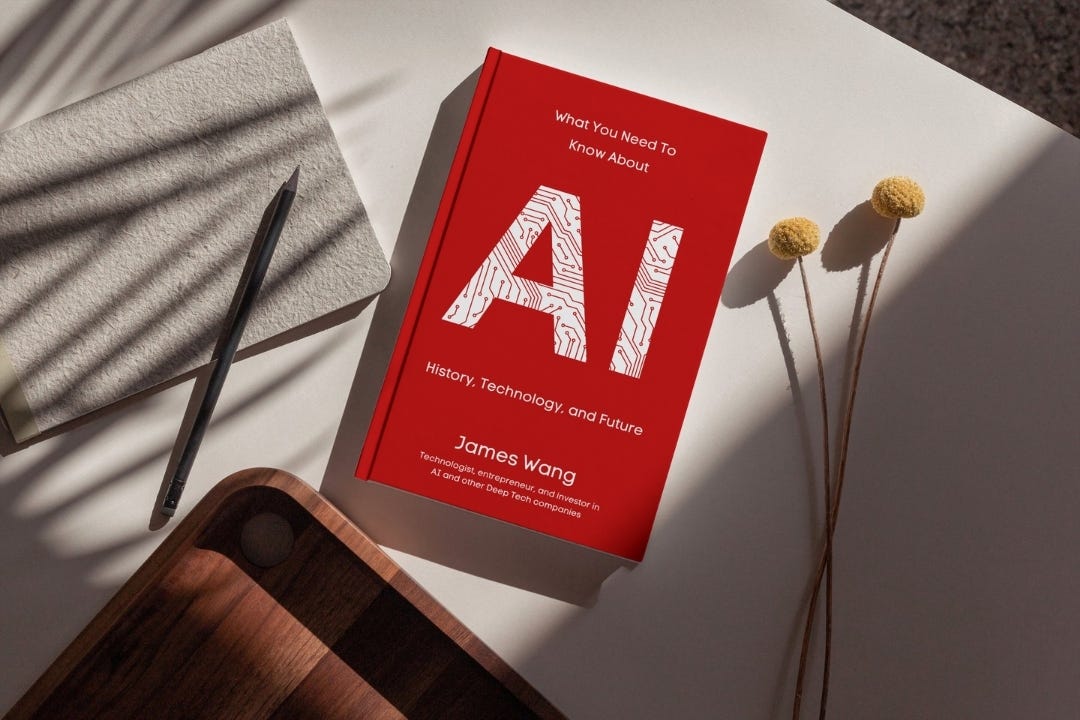

My book’s pre-sale is coming up, starting early January and running through the first week of February (if you want to follow, sign up here). As we get into the holidays, though, I’m going to have a few pieces that are quite different from the norm. Today, I will be talking about musings I’ve had while writing the book.

My publisher constantly harps on me to explain, clarify, and put out into the world why my book is original and why I’m the uniquely right person to write it. Substack, in its setup, is the same where it subtly (and not so subtly) asks you to explain why you’re different.

This makes sense. There’s just too much competition out there, and you need to pitch people on why they should read your stuff with their precious, finite time—both from an “attention economy” perspective and from the morbid, “We only have so much time on this planet” perspective.

As such, you’ll hear me self-promote plenty. You can probably tell from my tone that I have simultaneous disdain, yet total acceptance of its necessity.

But since it’s a given that I’m going to be talking everyone’s ear off about how great my book is, I’m going to do something entirely different here. Instead, I’ll talk about why I have continuously had doubts about writing the book (and, to a lesser extent, this Substack). Specifically, I’ll muse about the nature of creativity and originality—and, frankly, “Why would anyone care about what I have to say?” I’ll also explain where I come down on why people do.

Maybe it’s the holiday spirit, or perhaps it’s from binging book writers’ interviews from Evelyn Skye’s wonderful Substack/podcast, but let’s try this out. Obviously, this will be a more personal post.

What is original, anyway?

It was extraordinarily difficult to pick a title for the book. Basically, everything even vaguely gesturing towards “AI” “understanding” “knowledge” or whatever was taken. There’s multiple “AI Decoded.” There are tons of random and small variations to “Knowing” or “Understanding” or whatever other similar combination.

I considered doing something with Grok or Grokking (risking confusion with Grok or Groq in AI, despite the word coming from sci-fi), or “gestalt”, or something like it, but even those were taken. Eventually, if I kept going, I’d just be going off the deep end of throwing SAT words into my title.

That’s how I ended up with the working title, “What you Need to Know About AI.” Straight to the point and so many words that I figured it’d be “un-catchy” enough to not get piled on by all the existent and soon-to-be-existent books about AI.

But even my current working title has a children’s book with the same title, which I discovered later. I’m still not sure if I’ll actually stick with this title, but at least it’s unlikely people will confuse the two.

Oh, well. It’s not like I’m not used to it. When I was at Berkeley, I think I was the 5th or 6th “James Wang” there. And despite growing up during the dawn of social media (my senior year was literally the first year Facebook expanded from colleges into high schools), I’ve gone my entire life never being able to get a reasonable social or email handle (trivia: it’s why my X and Bluesky handle is “AJamesWang” which pokes fun at that fact).

Anyway, if just getting an original title is hard, how in the world can I write something actually original about this topic (or anything else)?

It’s easy to be “original”

It is trivially true that everything is original. It is also (more profoundly) true that nothing is totally original.

What do I mean by trivially “original”?

It’s very unlikely, if you sit down to write something, that it’s going to be a total copy of something else—at least if you aren’t literally copying. This is the logic behind years of rote, unoriginal book reports written by millions of grade school children over the years. It’s easy to pick up true plagiarism because the probability of a “collision” (to use computer science terms) is so unbelievable small that you can use fairly crude software tools to detect it.

Of course, AI and LLMs largely destroyed the smooth functioning of this paradigm of rote, unoriginal regurgitation that only forbids literal copying (which I think is a good thing), but that’s a different topic.

Nonetheless, if you write something of reasonable length it’s very likely to be “original” in a literal sense. That literal originality is also not particularly meaningful. It’s trivial. Obviously, as a writer of either a newsletter or a book, you want to be original in a much more material way.

You want to come up with new ideas. You hope to be original and creative and insightful and profound… and the list goes on.

But that’s also incredibly hard.

Truly original ideas are rare

PhD dissertations are the ultimate example of “original work.” They are definitionally meant to create new knowledge for humankind. However, talk to any PhD and they’ll explain that the work is seldom something sweepingly original.

It’s a tiny advancement in a highly niche, sub-specialized area. In candid and cynical moments, often over drinks, I’ve heard more than one PhD describe it as years sunk into researching something that barely anyone will have heard of and even fewer will care anything about. It’s still something they should be (and usually are) proud of, but it’s not really what movies like A Beautiful Mind portray.

That obviously doesn’t mean all academic work is barely noticeable incrementalism. Aside from stereotypical (and old) examples from a history textbook like Boyle’s Law or Einstein’s Special Relativity, I’ve repeatedly talked about how AlexNet and ImageNet made a deep impact on me early on (as a non-academic in a non-AI field).

However, the point is that there is a single profession in the world where true originality is the overriding goal. And in this profession, it requires radical scope narrowing and often the effort of years to get a publication out.

And even here, that true, material originality doesn’t happen. With the constant pressure of publishing original work, academia has been going through a replication crisis for years, with papers being totally unable to be repeated/validated. Occasionally, this is sloppy work from the pressure. Other times, it’s straight up fabrication.

Given this, how likely is it that my ideas are truly original?

It’s almost impossible.

There’s been plenty of times when I think I have a fairly unique take that I write and get out there on Substack, or X, or wherever. Given I’m not an academic, this is usually some kind of synthesis of AI’s technology and business implications that I put together. It’s quite common that I then find someone else has written about a very similar idea (or the same idea) at a similar time.

Sometimes, it pre-dates mine. Others, it post-dates mine. Nonetheless, I’m not egotistical enough to believe that in the post-dated cases that they’re all just copying me. I’m also too logically consistent, since if that’s true, then doesn’t it need to be that I’m copying them if they pre-date me?

In the case of the Substack, I figure that my takes over time would distinguish it.

Ironically, I heard this same idea on a Dithering episode a few weeks ago from Ben Thompson.

The other distinguishing factor are my unique anecdotes as an entrepreneur, investor, and venture capitalist. However, even with these, most of the stories that I share are specifically chosen because I know they’re not unique.

My story about speaking with an insurance executive joking about how paying for preventative healthcare is spending money today to save their competitors' money tomorrow? Peter Attia definitely has mentioned similar conversations. My story about how every newly minted robotics or ML PhD who looks at food services and decides, “I’ve come up with a wholly unique idea that no one has ever tried before—I’m going to a use a 6-axis robotic arm to automate the commercial kitchens!”? I get laughs from both experienced entrepreneurs and VCs because it rings totally true to their ears.

I use them as anec-data. But if someone wanted to press me on, “Did that really happen?” I know a chorus of other people can back me up.

Now, I may be quippier about some of these stories, but that’s mostly it in terms of originality.

Actually unique things, if not original

That last part actually gets towards what I think why people read my writing—or, getting philosophical, anyone’s (non-fiction) writing.

None of the specifics of my Substack, especially in terms of “what happened in AI news” or highlighting research papers, is totally original. I’m not even the best person to get this kind of update from because I don’t focus on it and am not a super frequent or “timely” writer.

None of my book’s history, or economic/business concepts, or technical overviews are truly never-before-seen. The interviews I’ve had with all sorts of amazing people get close to it, but if I’m to be totally candid, those people don’t have completely novel and unheard of thoughts either.

Of course, if you think about it, as a reader, looking for nothing but completely original concepts is absurd. You could likely get it through monkeys typing on keyboards and culling out whatever doesn’t actually form sentences and paragraphs, and you’ll likely get some crazy, original stuff there. Obviously, you also want it to be true and insightful.

Ultimately, I think you all read this because you trust me to get things at least mostly right. Additionally, while the individual pieces are not necessarily totally original, they probably haven’t been put together all in the same place with the exact same message. While that does have some shades of “trivially original,” I think that’s also you deciding to read because you trust my editorial choices.

Finally, I think some of what I write is quippy—so my unique voice in talking about these topics makes it more digestible or entertaining. (Feel free to tell me if I’m deluding myself. ChatGPT seemed to do so by describing my writing as “mostly measured and serious,” and only backtracked from some angry additional prompting on my side.)

This trust is obviously tough to find for someone who doesn’t know me. If you haven’t interacted with me in real life, seen me speak, followed along this Substack and just randomly come across my book on Amazon when it’s out, why in the world would you buy it?

Honestly, you probably wouldn’t.

Ideally, my short synopsis, marketing pitches, or whatever sways some people. But I’ve done an e-commerce startup before. I have no illusions that even for highly informed purchases that people read product descriptions that closely, let alone some random book on Amazon.

Ironically, it’s more likely my book cover, just by the nature of humans being so visually focused, will sway more people to buy my book without knowing/trusting me than my book description. I mean, I’ll aim for a good book cover, but even a truly inspired one has no bearing on what’s inside (or the author). “Don’t judge a book by its cover,” would not be a popular saying if people didn’t often judge a book by its cover.

According to my publisher, the actual way that most modern books get their purchasers is by word-of-mouth (and yes, sure, Meta and Amazon ads)—which makes sense, since it’s someone you know vouching for this unknown author.

I will now, duly, take this moment to plug signing up for pre-sale/book updates and request that you tell everyone you know when it’s available.

It’s really about you—and that’s hard

Getting back to the point though, I think this is why writing is so hard for so many people. Even if they don’t think through this from beginning to end, they subconsciously understand that people reading the writing (or choosing not to) is a judgment on them. Which makes it deeply personal and tough.

I have plenty of gripes about the book writing process. It’s just way longer, and stringing together a set of repeated (but not repetitive) themes for 50,000+ words is much harder than self-contained articles. My publisher (at least mine, probably others, though I don’t have enough experience to judge) is really annoying about citations for even what seems to me like common knowledge—and honestly would be in an academic paper—like “LLM” (and needing to go off and find some authoritative source to validate that it is, indeed, “Large Language Model,” and what it is). I also don’t get to use footnotes as liberally as I want to, or as much as I see some of my favorite non-fiction authors do (I’ll guess I’ll need to build up to being a Steven Levitt or Malcolm Gladwell).

However, that’s all minor. The harder part is when you take away all the artifice about “totally original ideas,” you realize that the reason people read is you. What they’re buying into is how you string together those not-totally-original ideas, their trust in you, and your unique voice—because you at least have that much that is unique to you.

So, what does that mean if someone doesn’t choose to read? Isn’t that a deep judgment on you?

Coping with the judgment

The reality, of course, is no. There are too many books out there. The “attention economy” is a whole thing. And it’s incredible the amount of marketing, in money and intentionality, that’s required to break through on anything—including a best-selling book.

That’s the rational part. The irrational part—which, rationally, I know I’m not alone on, for all the good that does—is that no one cares, or trusts enough, or cares enough. You’re not good enough. Or you’re a pretender or imposter to what you’re talking about, and people see through it.

And look: I’ve been in Silicon Valley a long time, gone through some famous accelerator programs here, done and heard thousands of pitches, and drank deeply of the Kool-Aid here about what kind of attitude is required to “make a dent in the Universe.” Additionally, I was at Bridgewater and got fully broke down and built myself back up to not fixate on my ego (or emotions) when doing things.

I have a far greater advantage than most in simply shrugging and pushing through this stuff, and I still feel it. I don’t actually have a great solution.

I just know for myself, sometimes, even though I insist from my Bridgewater training that I do not care or value mere encouragement with no information content… it still does help. A lot of people reach out either privately, or consistently engage with my stuff in a way that lets me know someone does care. I’m not trying to be a cursed “people-pleaser,” but it’s still quite nice to hear some people are pleased in reading.

Honestly, this is why I go out of my way to comment on Substacks that I see get relatively few comments (whether they are small Substacks with few subscribers, or ones with probably 1000x the views of mine). Even if tons of people get massive value out of your content, and you know it must be true (intellectually) because they subscribe and constantly read it according to Substack analytics, it’s something else to hear (or read) that sentiment directly.1 I feel it myself, so I figure others probably do too.

Ultimately, I know I’ll have to put myself out there, and ask, and beg, and jump up-and-down and get people’s attention (because they’re busy). I’ll cajole and beg for people to tell friends about the book. I’ll ask for harsh feedback, to hone my book to the best it can be and make it a worthwhile book to be endorsed. I absolutely want to do those things and they fit my rational brain just fine too.

However, I’m thankful for my community here, the cheerleading I already know I’ll get, and the (ongoing) validation from “encouragement with no information content”—because, I think, the reality is there is information content.

You put yourself out there, and ask, does anyone care?

Those responses back are the answer.

Thanks for reading!

As I explained here, I’m working on a book coming out in 2025 about AI: its history, technology, and future! Follow updates on the book release here:

It does take effort to be more than a passive observer—which is why even with thousands of subscribers, you can have relatively little activity. I make a point of trying to do more in cases where I think the content is great, but the “room” is kind of quiet. That room deserves to be less quiet. Just to be clear, there are still plenty of Substacks I enjoy (and I also think are great), but already are fairly “hoppin” that I’m happy just reading comments.

I enjoyed reading your take on the thoughts that ruminate around so many writers’ minds—thanks for your transparency about the process. And good luck on the pre-orders and book promo!

Substack is more about the relationship with the reader than the exact content, and most people don’t respect this. I don’t really have a view for how books fit in. Brave time to write one.