AI Gains Starting to Show in the Real Economy

US Productivity Data, Claude Cowork, The Future(?)

Claude Cowork launched last week. It wasn’t really greeted with much fanfare outside of AI/tech circles, though. To be fair, it isn’t really that different from an instance of Claude Code with a nicer UI wrapper around it for non-coders. I’ve been contorting Claude Code to do what Cowork does using MCPs and dumping documents into folders for it to read for a while now.

As Grace Shao covered, this movement towards AI working to do things in the real world is also a trend in China—most concretely with Alibaba launching their own Qwen Assistant last week as well.

This is all part of a wider trend of accessible agents doing things for people, like what I pointed out in “The Boring Phase of AI.”

Even though Claude Cowork may not be technically impressive, it’s still a potentially major milestone. Calling back to my recent decade review, it’s not like ChatGPT was a magical step beyond what the GPT models (GPT-3, in particular) demonstrated for years. But ChatGPT made it accessible to a wide audience, and that accessibility was transformative. A technology that only experts can use is not really a technology yet—it’s a prototype. The moment regular people can pick it up and get value from it is when the real economic effects begin.

Is AI productivity starting to show in the data?

Economic statistics are always lagging indicators. We put enormous effort into trying to know what has already happened—and often get it wrong, seeing as government agencies often revise data (sometimes significantly) months later.

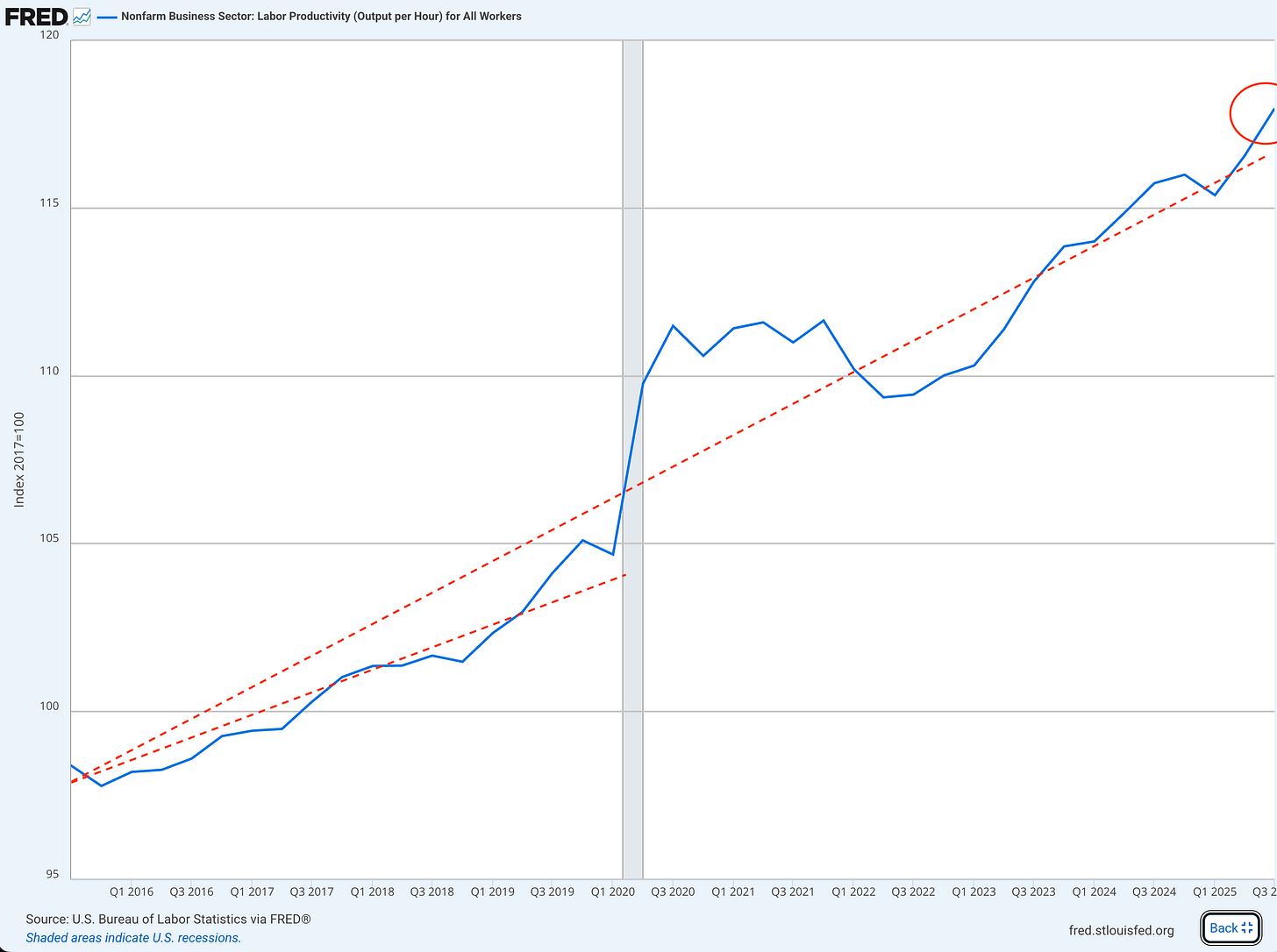

Among these kinds of stats, productivity data is notoriously hard to read. Even in hindsight, years later, we’re often trying to build narratives and read tea leaves. As such, it seems kind of silly to try to make much of a single datapoint, especially one that you have to kind of squint at to see its relationship to the trendline.

Nonetheless, recent BLS data for Q3 2025 was notable. Nonfarm business sector labor productivity jumped 4.9%. Notably, output increased 5.4% while hours worked barely budged at 0.5%. That was a classic “pure” productivity gain, which looks a lot like fast-moving technology adoption.

In the chart below, I draw two lines—first, the trend “before” the recent period. And secondly, the one after 2020 (which has some oddity because of COVID suddenly causing labor to collapse with lockdowns). Again, I know we’re squinting, but it does seem to be a break in the line—which would likely just be seen as noise without the underlying context that the economy is still fairly strong, hours worked didn’t really fall (i.e., not like COVID’s lockdowns), and output jumped a lot. We’ll obviously have to keep monitoring it going forward, but it would be fascinating if this is the start of a real trend.

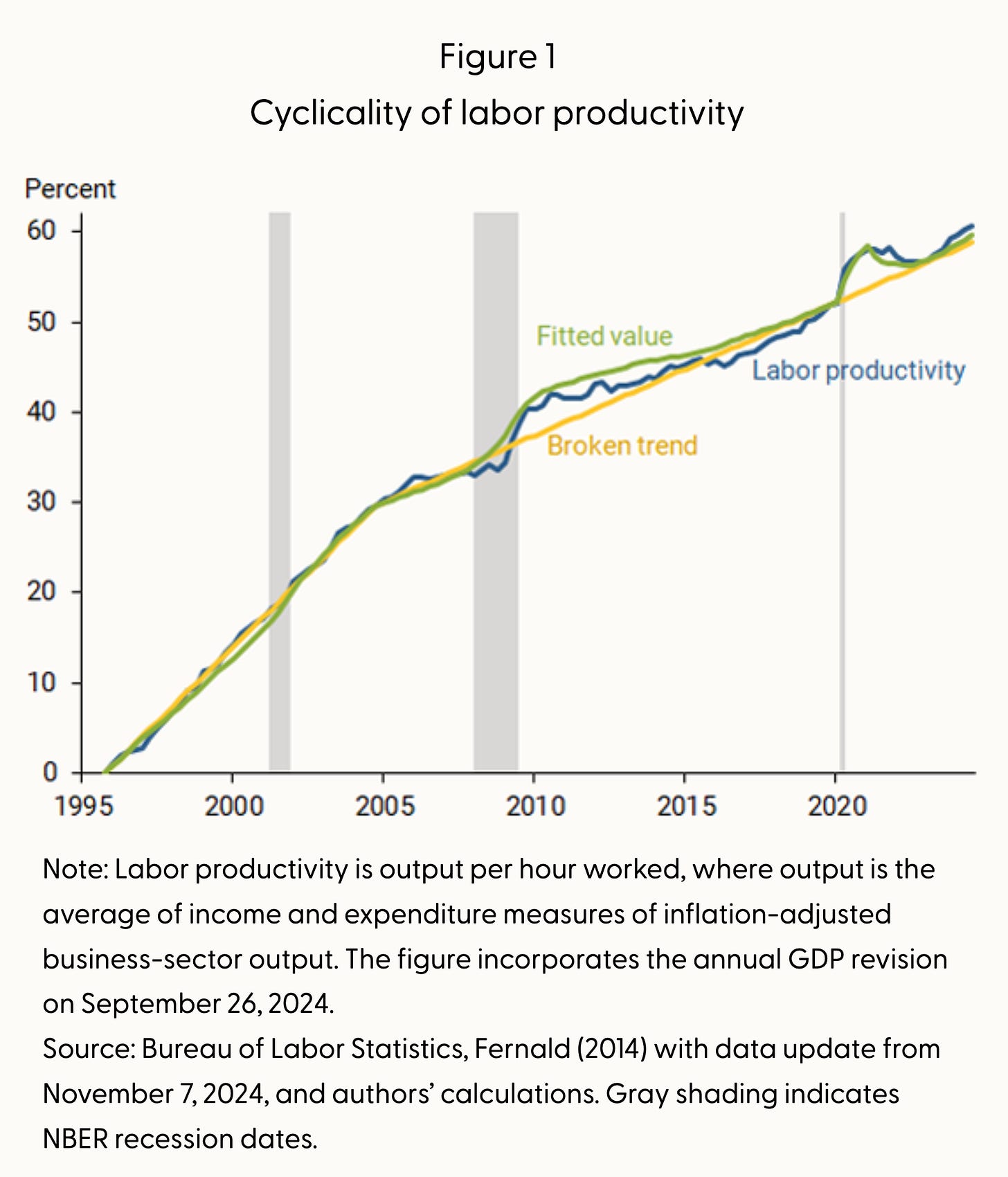

Just for context, it is worth noting that productivity data is cyclical. During recessions, productivity tends to spike—not because workers suddenly got smarter, but because (in classical theory) less experienced workers get laid off first, raising the average skill level of those who remain. (If you want to be more cynical about it, workers are laid off and the remaining need to pick up the slack—at least temporarily and perhaps unsustainably.) Capital per worker also temporarily rises when you have fewer workers using the same equipment. As the economy recovers, these effects unwind.

The San Francisco Fed shows a similar analysis and puts it into broader context. Specifically, our lost decade(s) of productivity since around 2005. 2008 temporarily spiked it back up with mass layoffs, but it’s been sluggish as a whole.

Why Do We Care?

More productivity does generally seem good, but why does it matter? On a macro level, productivity helps define how fast the economy can grow without inflation. This is because taking away population growth (which is one source of GDP growth) and exports, what your economy can sustain is defined by how efficiently you can build stuff.

Think about it this way: if everyone wants to buy more stuff, but we’re unable to actually make more stuff faster, what happens? Prices go up. PC gamers are feeling this with the RAM squeeze (driven by data center demand).

We’ve already had stubbornly high inflation, in part because of high spending in the US, which has been at near wartime levels for the past few US presidential administrations, and not enough central bank tightening. The point of fiscal austerity and monetary tightness is to rein in the economy when it is running “too hot”—meaning too far above potential GDP... which is defined by productivity.

Now, the stock market is not growth. It’s a market.

Notably, as my former colleague Josh Blanchfield recently pointed out in explaining why the stock markets of Colombia, South Korea, Spain, and Greece were the top-performing markets in the world (116%, 100%, 83%, and 79% return in 2025 respectively—the US is #38!):

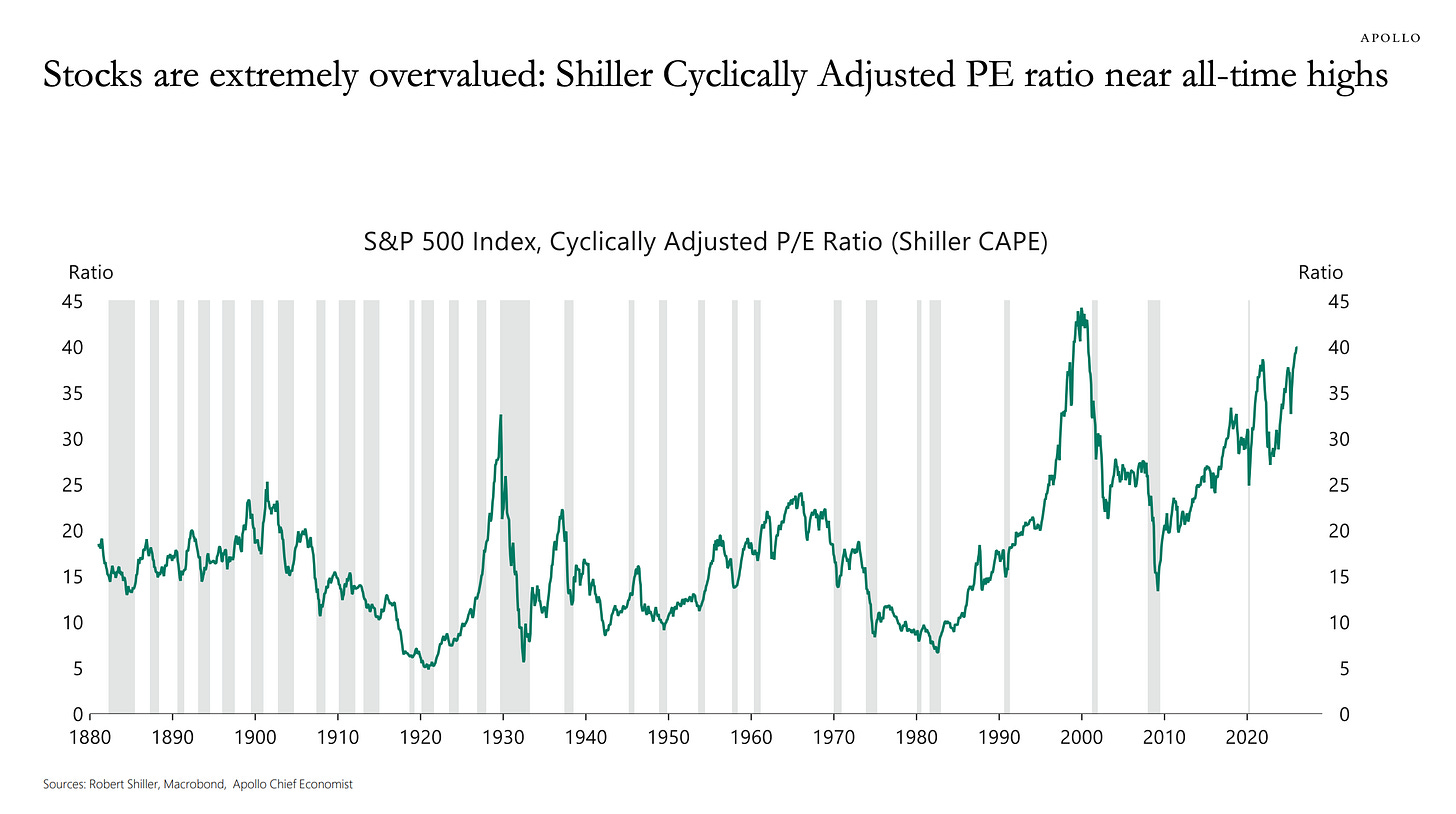

Profits are not the same as equity returns. It matters what you pay for those profits.

Nevertheless, it would certainly help if potential GDP were much higher given how ridiculously high the pricing is for the US stock market—which is essentially at historical highs relative to earnings. If the ceiling of the economy to grow rather than just create inflation were much higher, one could make a far, far better argument for why US tech stocks (largely, the “Magnificent Seven”) aren’t crazily overpriced.

That all being said, while the US stock market is now a huge store of wealth for many Americans (... and many others in the world), the stock market isn’t the real economy. If AI really has the ability to massively increase productivity like some of its most fervent (but non-insane) boosters claim, it would make a huge difference in people’s standards of living.

It’s Still Early

Regardless of where productivity actually is, AI adoption is still in its early stages. Yes, ChatGPT exploded onto the scene in late 2022 and sent shockwaves through the tech world. Yes, companies have been scrambling to integrate AI into their workflows. But if you look at actual enterprise adoption data, most organizations are still experimenting.

If we’re already seeing productivity effects at this level of adoption (enough to show up in productivity stats), what happens when AI tools become truly integrated into day-to-day work?

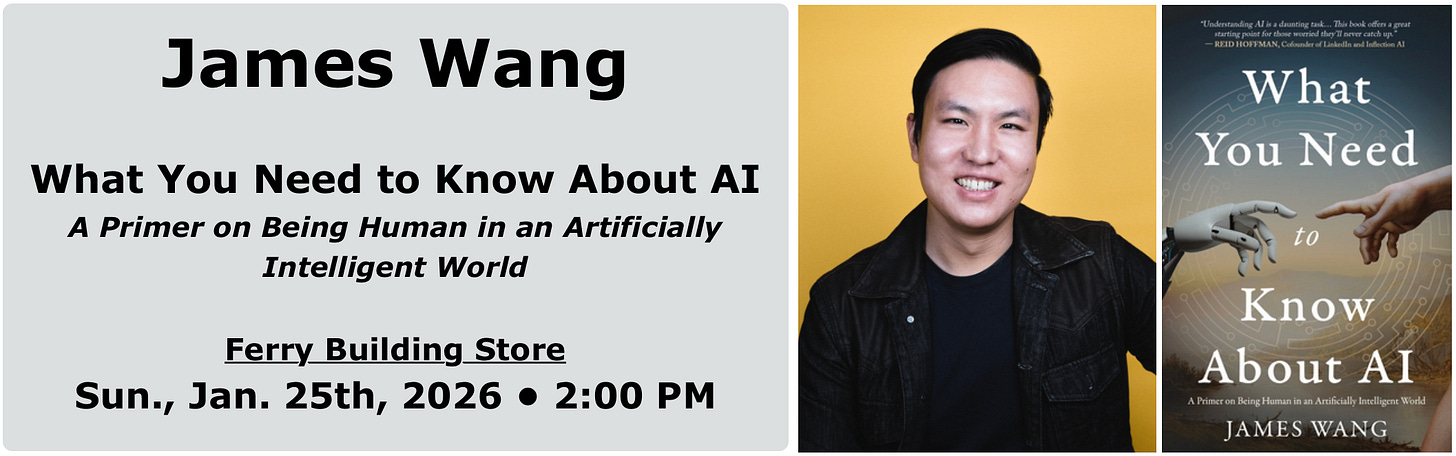

Book Event Next Week

If you’re around San Francisco, I’ll be doing an event at Book Passage on Sunday January 25th at 2pm! I’ll be doing a reading of my book What You Need to Know About AI, signing books, and answering questions from the audience. Hope to see some of you there! If you’d like an event reminder you can sign up here.

Is there any correlation between AI adoption (at the business level) and productivity growth? How granular are the statistics?

It’ll be interesting to see whether this blip becomes a trend. But a thought, industry mix will also impact productivity with certain industries being less productive than others. Do you know the impact of that?