Is AI a Winner-Take-All Market?

A critical question for investors in AI

Hit-Driven Markets

When I was in college, I had spent a summer interning at a games industry research firm. One interesting aspect to it—even in the early 2000s—was that the games industry already looked like less like nerds-in-a-basement and much more like the movie industry. “Call of Duty” spent more on marketing than many blockbuster movies, and major publishers were set up like the biggest Hollywood studios.

This isn’t an accident. Both are hit-driven industries. A few major hits make or break a studio/publisher’s financial results—and suck up a lot of the total dollars in the entire industry.

Think about Disney-Marvel’s superhero films or the big-budget blockbusters that get most of the advertising space on billboards, TV, and display ads. Think about Call of Duty, World of Warcraft, The Sims, and similar. Major movies and games are much more similar than different in funding, marketing, and outcomes.

Venture Capital is also Hit-Driven

Venture capital is another one of these categories. It doesn’t operate like most of the finance industry, which usually relies on diversification and numerous tiny bets to smooth out wild ups-and-downs. In venture capital, the wild ups-and-downs are precisely the point—you can only go down to zero, but you can go up to 10, or 100, or even 1000X for an individual company.

In reality, reaching 3-5X for the entire fund puts a venture capital in the top echelons of the industry—after all, even if you have one or two winners, they still have to make up for all the losers. Many funds never make it to that, and certainly very few do so consistently. This is especially the case when very few companies constitute the bulk of returns. What if you just missed the industry’s rocket-ship company?

In any case, this is why VCs like winner-take-all industries—basically, stuff that will become monopolies, or at least oligopolies, in large markets.

Think Google. Or Facebook. Or Uber. The details are different in each. As Google continues to argue in its defense in antitrust cases, “competition is just a click away”—but obviously, everyone overwhelmingly uses Google. Facebook is a classic network effect, where you are there because everyone else is (and is weakening because that’s less and less true over time). Uber is also similar in “it’s where both the drivers and riders are,” even if the actual network effect ultimately proved to be much weaker than the other two examples.

A massive market may not be interesting split into a hundred or thousand different pieces. A massive market that goes to one single (or few) winner(s)? That’s much more interesting.

If you don’t have an argument towards consolidation in a big market, it’s a bad investment for VC. In a way, it’s quite ironic: these types of companies have the highest risk of failure, but the economics of VC (like blockbuster movies or AAA games) means that if it can’t be a massive hit, it’s a guaranteed failure. It’s better to have a chance at the big upside, rather than definitely lose.

This, of course, brings us to the title of this entire article—how does AI work here?

So, what about AI?

Given I am a VC who has put money into AI, you’d think my answer is: “Yes, definitely!”

Eh, well, it’s complicated.

There are plenty of VCs who seem to think that AI is a winner-take-all market. The entire “Foundational Model” thesis is essentially this. One AI will rule them all.

I’ve said, repeatedly, how skeptical I am of this idea—specifically because I don’t think there are dynamics that lead to winner-take-all. If anything, this is an area that, I think, will have a ton of competition, and thus destroy the economics of those who try to compete in it. If there’s any saving grace, it’s that it is (currently) ruinously expensive to compete, which is a better argument towards a natural monopoly (see below). The not-so-saving grace is there are competitors like Meta in it that are perfectly happy to spend ruinous (to businesses smaller than them) amounts of money, funded by their other operations.

Relative to some internet companies—say, search or social networking—AI is likely more “vertical.” This means it will be broken into markets by use-cases.

So, what does this mean?

Google dominates Internet search. Not “search for dentists” or “search for cars”, etc. (There was, once-upon-a-time, an argument that this would be more of a thing—hence Yelp, ZocDoc, and similar companies)

Will ChatGPT (or Claude or Mistral) be the one-true-AI for consumers, manufacturing, healthcare, etc.? From what I see, I don’t think so. I’m not even sure LLMs as they exist today will be that.

Horizontal vs. vertical consolidation

Part of the nuance here is that consolidation doesn’t just go in one direction.

Google and Facebook are a good example of horizontal consolidation. It doesn’t matter what industry vertical it is—they dominate all of them because they dominate (or did) their areas for search and for social networking.

Horizontal consolidation is typically more attractive for a VC. Instead of dominating one industry, you can dominate all of them (within your business area). That’s definitely better.

Going back to the movie and gaming industries, movies and games are within their areas just a big “entertainment” market. You don’t really have a movie market that appeals more to tech workers vs. healthcare workers. It’s less “vertical”-ized in terms of mass media. This may be changing with streaming, indie games, and similar kinds of trends, but this has been and is still the main way it works. As such, hit-driven makes a lot of sense.

Vertical consolidation, as in, within industry, can still be ok. However, inevitably, “search for restaurants” or “search for dentists” is not as big as “search for everything.” Nonetheless, if this is actually the structure of an industry, this can be big enough, if the company actually does dominate all of it within its area. You have to do a lot more “sharp-pencils” kind of analysis work to make sure it is big enough even if you win.

After all, there is still no guarantee that the new modality/market takes root at all (e.g., if Internet search as a thing never took off at all or just didn’t persist).

“AI” business use cases don’t naturally tend towards horizontal consolidation

AI has some severe problems with the “winner-take-all” thesis—which, with our new terminology, we can clarify is a bet on horizontal consolidation.

This all leads back to interconnectedness in industry structure. This applies to both data and referenceable customers.

Industry-specific data. AI needs a lot of specific data to be particularly useful outside fairly generic queries. It’s fragmented enough that it’s not like having all hospital data, say, will actually give you a leg up in getting, say, contract manufacturers, to give you their data. Or does it automatically get you that data? No.

With Google, it’s all one connected (literally) Internet. With Facebook, it’s one social graph. With these verticals? Not so much.

This actually looks like enterprise software of the past few decades. It’s possible to have EHR/EMRs (electronic health/medical records) and ERP (enterprise resource planning) software with entirely different large companies—like Epic vs. SAP—supplying them, even though their “base functionality” has many similarities.

Referenceable customers. This is actually a really similar point to the data point. It’s worth calling out because even if the data is very fragmented, you could potentially get around it by having relationships glue multiple industries together. Specifically, if you could use one particular customer to sell into a different customer more easily—because of trust or even competition between customers—this would allow you to quickly expand and be a little more “winner-take-most”-y.

Going back to my previous example, though it applies across most verticals, a hospital would not care that an AI company has a manufacturing company as a customer, or vice versa.

They would care about customers within the vertical, as in other hospitals or manufacturers.

By the way, it gets even worse. I’ve made this point before, but LLMs aren’t the only models that exist. They might become the user interface for accessing other models (i.e., multi-modal models), but they are definitely not going to be the best at doing everything. LLMs can never hope to do what AlphaFold is doing, for example, and may not be the right choice for drug discovery, material design, and numerous other cases where AI can be applied.

That makes it even more likely that different companies with not only entirely different proprietary data and referenceable customers, but also entirely different model modalities.

Again, this can still make it the case that these individual markets (with careful analysis and ideally winner-take-all dynamics internally to the vertical) can still be worth it, but it will not be a Google-style outcome, which is what the scale of investments tends to imply.

The counterargument—isn’t there one horizontal market in consumers?

It’s important to stay open-minded. I’m pretty open to being wrong—it’d be dumb to be overconfident, given these are new markets with new technologies—though this vertical-vs-horizontal viewpoint is my best guess, based on all available data and the trends we see, as to where things are going.

However, what is the bull case for these foundational model companies (apart from me just being wrong, and these models being the AIs-to-rule-them-all)?

I can see a few different arguments:

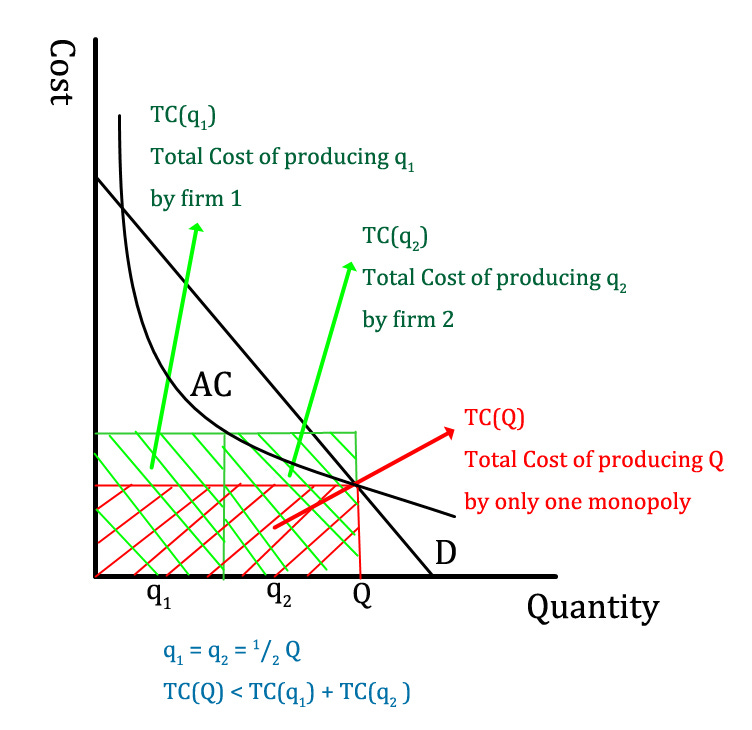

Economies of scale: The scale of computing means, similar to semiconductor fabrication, more scale = cheaper costs. We’re back to natural monopolies. I don’t think this is the case, and have several articles explaining why.

Single-market in consumers: Maybe business customers are very vertical, but perhaps consumers all consolidate down to a single LLM. After all, consumers like Google for search (… putting aside the immediate counterargument that businesses do too). Unfortunately, there’s already pretty serious questions as to how much value there is in LLMs/generative AI. Besides that, I think market power is muchmore concentrated in the hands of entities like Apple, who own the means of accessing the LLMs, not the model companies themselves.

“Singularity” take-off: The viewpoint that LLMs are the key to general artificial intelligence (GAI) and human or human+ level intelligence is getting a lot less popular as we go on. However, this certainly would be an argument for why this might be wrong, though I wouldn’t put money on it.

These are all at least colorable reasons for why you might disagree with my view. I don’t find it compelling—but you might! And obviously some other VCs seem to find something here compelling, or at least are willing to roll the dice on it.

Ultimately, we’ll have to see—but at least for now, I’m seeing a much more diffuse AI future where it’s embedded in countless areas, but not as an all-encompassing model or company.

I have an alternative hypothesis for the horizontal fragmentation in AI (not just LLMs). Antitrust issues aside, the lack of horizontal integration boils down to a simple NPV argument straight from a business school curriculum. Outside of mutual fund management, cloud computing and data storage have been historically some of the highest-margin businesses, supporting a true oligopoly in those markets. So why would Big Tech dive into areas like healthcare, where margins are basically nonexistent? Instead, they prefer to invest selectively, as Alphabet has been doing through Google Ventures, for example.

So, the trillion-dollar question is: How long will Google, Microsoft, Amazon, and Meta continue to focus primarily on cloud, data centers, and (increasingly) GPU markets, without making major moves elsewhere? It could be a while, which, I suppose, aligns with your hypothesis. 😉