Let's talk about AI power costs

It's important, but a lot of recent attention has been concern-trolling

Recently, concern over the power costs of AI has been growing, with more and more articles penned on the topic. Perhaps the only thing that has been expanding faster has been confusion on exactly how much power AI is consuming (and the difference between energy and power).

Yes, I know I sound dismissive—even though one of the constant themes my Substack harps on is that AI is not like traditional software.

AI has real costs for every LLM query (inference), whereas you can basically round every individual web request for most traditional software to zero. In aggregate, cloud computing costs may still cost millions, but that’s often serving billions or trillions of queries.

For AI inference, a lot of that real cost is in not-insubstantial power bills from running that level of compute.

So why am I seemingly rolling my digital eyes at the topic?

In reality, I’m not—at least not at the overall topic. It’s a material policy question. There are smart researchers thinking about the topic. Base load (which most renewables cannot address) is already an issue, and—folks smarter about commodities and energy than I am—tell me that even the nuclear power plants that haven’t gotten shut down are running rather short of fuel. More strain on base load, which AI is, is something we should think hard about, especially if the technology takes off.

Getting our priorities straight

My main issue is that most of the current discourse about the topic is largely concern trolling, disguising suspicion of technology and those who work in it with seemingly reasonable concerns. These concerns are generally hand-wavy with vague projections of energy doubling/tripling/10X in some number of years and isn’t that horrible because we have climate change?

First off, we can project anything. I’ve already made it clear what I think about projections that AI training costs will exceed total US GDP (and given how the line goes, total global GDP in short order).

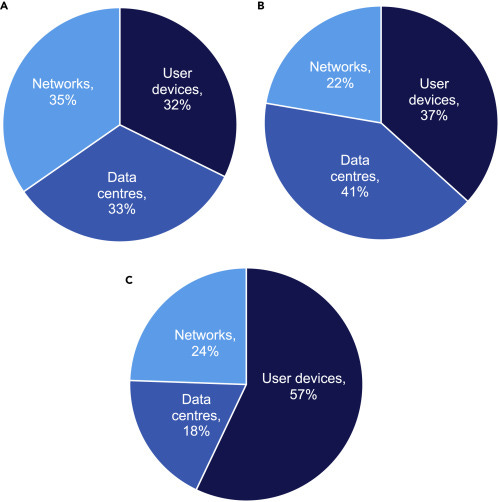

Second, bringing up climate change in the context of this specific problem like it’s “one of the really big problems” is infuriating because our carbon footprint from all computing is fairly small—researchers at Lancaster University estimate between 1.8-2.8% (including all data centers and your smartphones/devices and all networking).

Transportation (most of it cars) is around 20%. Livestock is 10-20%. Globally, we also keep shutting down nuclear power which has been making it harder to hit carbon reduction goals as well.

When AI is a fraction of the data center figure that is a fraction of 1.8%-2.8% of all “ICT” that encompasses smartphones, computers, laptops, and networks… What are we ultimately talking about? A small fraction of 0.5%, maybe? Perhaps 0.1%? Less?

When it doubles, it’ll become… 0.2%?

One of the difficulties is AI power consumption is not yet significant enough for us to really know. When power consumption really reaches a large scale, we’ll notice. But right now, it barely shows up, so we’re truly flying blind on what’s the real footprint. Many of the most hyperbolic “concerned” articles fearmonger about the size of the figure while giving utterly no details.

What is really the power consumed per LLM query?

I don’t know. No one really does. But this isn’t because it can’t be measured.

It’s because it varies wildly depending on the hardware you’re running it on, the kind of model (remember, one of ChatGPT 4o’s advantages was it was smaller and cheaper—hence more power efficient—to run), and many other variables like context-lengths and specifically, what else is being used (especially in multi-modal models).

One of the most evocative “back-of-the-envelope calculations” that’s making its way around radio, podcasts, and TikTok is Senior Research at the Allen Institute for AI Jesse Dodge’s statement that:

One query to ChatGPT uses approximately as much electricity as could light one light bulb for about 20 minutes.

I’ve actually looked around to try to find the envelope, or some details on how he derived this. You’d need to know quite a bit of detail about ChatGPT and OpenAI’s hardware to get a real answer here… but I don’t actually doubt his overall figure. This sounds ballpark correct to me, and we don’t need to precisely calculate the amount of power OpenAI uses per query.

Someone recently asked me the same question, and—not being a frequent connoisseur of TikTok—I hadn’t heard about Dodge’s math here. My completely back-of-the-brain, largely intuitive estimate (knowing the general models and hardware involved and running some of these things locally myself) was a few seconds of an air conditioner.

Assuming Dodge is right, these numbers actually line up. An “average” 60W incandescent-equivalent LED is 7–9 watts. A middle-of-the-road AC is, 2500W.

That 7W LED bulb for 20 minutes is 0.007 kW x 0.2 hours = 0.0014 kWh (remember kids, energy, and power are different, and you’re charged for power).

That equivalent amount of time for a 2500W AC to reach 0.0014 kWh of power consumption is 0.0014 kWh / 2.5 kW = 0.00056 hours → 2.016 seconds.

To be honest, we probably both largely intuited these numbers (I know I did, and I actually searched for quite a while for the scratch-work for his), but 1) they’re actually very consistent with one another, independently, and 2) I’m also pretty sure our experience with these technologies have made us both pretty good at guesstimating.

Now, with this less impressive “seconds” figure, I could be a pain-in-the-ass and—in bad faith—ask, “Well, isn’t it worth you turning off your air conditioner for a mere 2 seconds to maybe help diagnose someone’s grandmother’s cancer/disease?”

In reality, we’re not doing disease diagnosis with ChatGPT, this is the exact type of false trade-off I’m criticizing, and no one in a hot climate is turning off their air conditioner for anyone’s grandma. My California readers won’t understand.

More seriously, even though it sounds less impressive than 20 minutes of a lightbulb to a layperson, it doesn’t obviate the actual good faith questions raised about AI power consumption. 2 seconds of an air conditioner is not small. I know seconds sounds small, but air conditioners are huge power hogs as well.

So, do you care, or don’t you?

Nuance is often lost in today’s world. I know I sound like I both am dismissive of the power/climate impacts of AI, while at the same time pointing out that each individual query is actually a non-trivial amount of power.

The reality is AI is still small today. Even if it grows in the future, there’s no guarantee it will be the same kind of power cost as today. In fact, there’s probably a forceful argument against that.

I mentioned before that the extrapolation of the training costs was dumb. Other than the fact that society will not allocate all GDP to training ChatGPT 8.0, technology does rapidly change and improve.

Inference will as well. In fact, it already has. In a Politico Tech interview, Josh Parker, NVIDIA’s Senior Director of Corporate Sustainability cited that AI inference is already, just in two years, 25X more efficient using NVIDIA hardware.

Now, he’s obviously a biased source. After all, this is also basically Jensen Huang’s argument that he’s been pitching for years before the current AI boom that “The more GPUs you buy, the more you save.”

Putting aside that he sounds like a daytime infomercial salesperson asking you to buy more Slapchops right now for just $9.99, he does an underlying logic here. Newer GPU architectures are much more efficient and, at scale, can actually save companies money.

Anyway, the point here is, it’s really difficult to know what the power consumption will actually be. Besides that, if we get to the point of constant, scaling AI workflows, will we then see data centers built in colder places (a substantial portion of cost is also cooling data centers)? Will we see data centers also pop up in areas with a lot of renewable energy, like solar, wind, and (above all because it’s constant load) geothermal?

Maybe. Probably.

Given that, it’s really difficult to actually know what the carbon footprint of AI will be, especially at this fairly nascent point.

And, look, no corporate overlord is sitting around laughing manically, draining their bank account from power costs, thinking about how great it is that they’re destroying the planet.

They care about their bank account.

And inherently, that means they need to care about the power efficiency of AI queries, which is fairly poor right now compared to what it will likely be in the future.

Relative to many other activities, this is a cost (in money, power, and carbon impact) that can likely be brought down substantially by technology change. In doing so, this technology will be fairly eagerly adopted because it is also aligned with these companies’ profit motive. As such, I think we can reasonably expect this cost (which equals power cost and carbon footprint) will come down a lot over time.

This isn’t crypto

That should be the conclusion of the article, but there’s still one last point to touch on. From other non-industry friends, I’ve gotten the question: isn’t this like crypto?

Those who know me, including friends who are very much into crypto, know I’m… not the biggest fan of crypto. As such, this comparison that has come up more recently has never failed to elicit a rather frustrated sigh on my part.

First, let’s narrow to “crypto” in the popular parlance: cryptocurrencies. Not blockchain, and definitely not cryptography as a field.

Now, putting aside how much societal value cryptocurrencies actually generate (… which I’d argue is substantially less than AI), it is quite different from AI.

Cryptocurrencies used to be mostly proof of work. Without getting into the exhaustive details, this is the “artificially hard math problem” that both secures the network and gates the creation of new currency. As such, crypto—and Bitcoin as the first in particular—was designed to be expensive. Computational power, which has always also translated in power cost for cooling and running it, is the limiting factor.

Now, keep in mind, these are not useful math problems. They don’t inherently do anything. They are entirely arbitrary make-work problems to enforce artificial scarcity of the currency and distributed conformity of transactions.

This is why, instead, a lot of cryptocurrencies, including Ethereum, moved to proof of stake (same article). Instead of using artificial math problems, the biggest holders of the cryptocurrency basically control it and get more of it as transaction fees. (Wait, is that “the rich get richer”? Yes, indeed it is). Anyway, the main point of this is you no longer need to do hard problems that cost a lot in direct computing power costs and cooling costs, at least for many networks.

This should be encouraging to those viewing AI as similar at all to crypto and are concerned about power consumption. The history has been fairly relentless in trying to drive down power consumption. Proof of stake was a big step, essentially eliminating the vast majority of computational cost, but even on remaining proof of work networks (like Bitcoin), “no one mines using GPUs” anymore. It’s just not profitable.

Everyone, because the math problems are fixed, relative to AI (which is a moving target, hence why I’ve argued on multiple occasions probably will stick to GPUs), moved onto much more power-efficient ASICs to mine.

As said, I don’t think AI will move in the direction of ASICs and away from general-purpose GPUs for a while. However, I do think the market will pressure AI hardware to keep getting more and more efficient in the same way.

After all, power costs money, which means all profit maximizing entities will want to minimize it—which also aligns with what society wants in terms of power use and climate impact.

Interesting, thanks for sharing your thoughts. I do wonder, though, how AI is possibly undoing the efficiency gains from data centres of the past twenty years. It seems like we're headed back to square one for a problem we solved a while ago through efficient hardware and cloud consolidation. Simply producing more efficient GPUs won't get us there again.

That being said, your reasoning does convince me AI energy consumption is less of an issue than many make it out to be.