White-Collar Apocalypse Isn't Around the Corner—But AI Has Already Fundamentally Changed the Economy

Software Alone Makes The Skeptics Wrong. Everything Else Is Upside.

Nate Silver thinks the singularity won’t be gentle. Noah Smith says you are no longer the smartest type of thing on Earth. On top of the software sell-off in stock markets (“SaaSpocolypse”), non-technical pundits have suddenly clued into Claude Code and are predicting job doom.

But somehow, at the same time, a new NBER study of 6,000 CEOs just found that nearly 90% report AI has had zero impact on employment or productivity. And Freddie deBoer is so frustrated by AI boosterism that he’s offering Scott Alexander a public $5,000 wager that the economy will remain basically normal through 2029.

This is where we are. One camp is suddenly terrified (again) by AI’s power. The other camp is convinced the whole thing is a fever dream that will dissipate like crypto or the metaverse (a point folks like Brian Beutler make every now and then).

It’s all extremes. All or nothing. We’re either all screwed, or it’s all going to nothing.

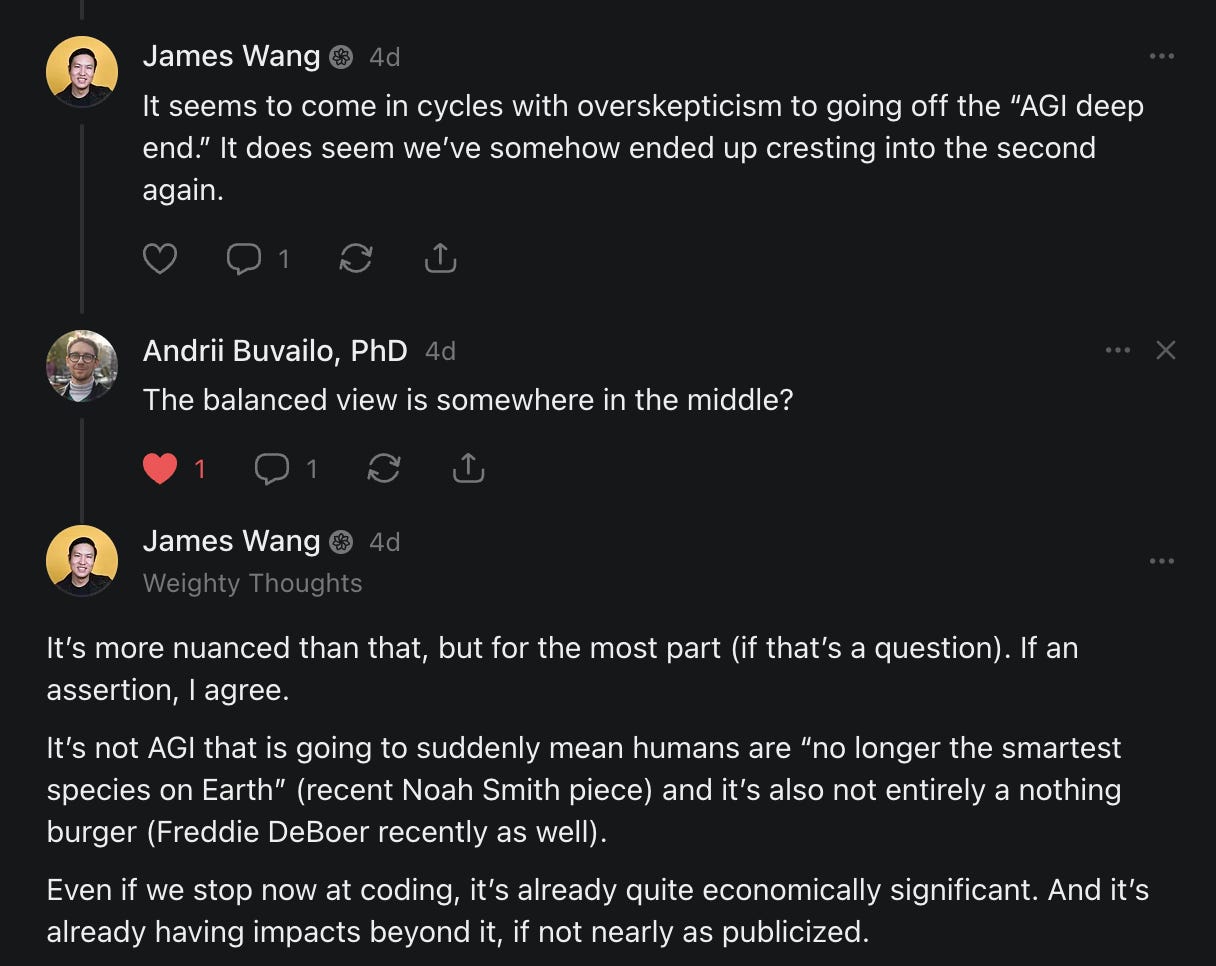

The reality isn’t that. I had an exchange recently with Andrii Buvailo, PhD that I think captures where most thoughtful practitioners actually land: it’s somewhere in the middle. AI is real, it’s doing real things, it’s not going away—and it’s also not about to make the economy unrecognizable by next Tuesday.

But here’s the thing: whether you’re in the “it’ll all come to nothing” camp or the “we’re all screwed” camp—nobody’s happy. Everyone is very downbeat about all of this. It seems to be the theme of the times.

There’s a recent interview on Adam Savage’s Tested with Ryan Norbauer—a designer and propmaker who spent five years and hundreds of thousands of dollars of his own money building what he considers the perfect mechanical keyboard. Around the 29:30 mark, Norbauer says something that stuck with me:

He talks about wanting to physically inhabit or touch something that “feels free from the disappointments of everyday life.” And then he connects it to growing up:

I think that this is why I loved Star Trek growing up as a kid. I grew up in West Virginia. I was a very nerdy, bookish, weird, gay kid and so you feel a little bit alienated by real life. And on television, there was this incredible vision of the way things would inevitably be in the future. Everybody was going to be nice to each other, tolerances would be accepted and celebrated, and everything was going to be great. So I desperately wanted to step into that world... It’s like the future is gonna be amazing. It’s right around the corner...

Maybe reality sucks, but the future is going to be amazing... Cultural differences will disappear and we’ll all get along, right? Everyone is going to be so smart because they have access to infinite information. It’s not so possible to believe in that idea anymore.

Which I think is a sad encapsulation of what we’re seeing from the commentariat. Notably, in the west—China is quite different. As per afra in “An AI-Maxi New Year”:

What connects these stories is what they reveal about disposition. The Chinese society, from a world-renowned auteur to the hundreds of millions watching the Gala, is broadly, strikingly optimistic about AI. The reflexive existential dread so pervasive in Western discourse is largely absent.

The thing is, this is the same technology in the US and in China. And the future really can be amazing... though only if we think about this all rationally and properly handle both encouraging its development—and guardrailing with the right regulation. We need to be smart in thinking about tradeoffs... which is not really a feature of most commentary or politicians these days.

So, let’s talk about what’s actually happening.

It’s Definitely Not Going Away

Whatever you think about AGI timelines or the singularity, one thing is clear: AI has already fundamentally changed software development, and those changes are already showing up in the data.

I wrote about this recently in AI Gains Starting to Show in the Real Economy—Q3 2025 BLS data showed nonfarm business sector labor productivity jumping 4.9%, with output increasing 5.4% while hours worked barely moved at 0.5%. That’s a classic “pure” productivity gain, the kind you see when technology adoption is actually working. I know we’re squinting at a single data point. But it’s a notable one.

Now, the Fortune article I linked above—the one about the CEO study—will use this as a gotcha. See? CEOs say nothing’s happening! They’re not wrong about the macro picture. As I said, it’s early.

But they’re making the same mistake people made with IT in the 1980s. Robert Solow’s famous line—”you can see the computer age everywhere except in the productivity statistics”—was true in 1987. By 1997, productivity growth had accelerated to nearly 3%. Computers didn’t suddenly start working better. Organizations figured out how to use them.

Organizations today don’t actually know how to use AI. Except, as said, in software (or rather, they’re starting to here). Claude Code. OpenAI’s Codex. Google’s Antigravity. And claims that many software developers have literally stopped writing any code. I can personally attest to a similar phenomenon in my own workflow—though I will assert that it’s pretty important to manage/oversee it!

Whatever you think of the claims, it is pretty clear that something is happening in software.

The Floor Argument

Here’s my proposal about how to think about this. What’s the minimum reasonable economic impact we should expect from AI, if we limit it to its single best use case?

AI coding assistants have real data behind them now. The most credible evidence comes from MIT’s field experiments across Microsoft, Accenture, and a Fortune 100 manufacturer. Nearly 5,000 developers. Real companies, real work. In short, the results were that access to an AI coding assistant increased weekly task completion by 26% on average.

Let’s be clear: we shouldn’t just uncritically take this as gospel and do something stupid like multiply it by GDP. Let’s pick that number apart and figure out how it applies.

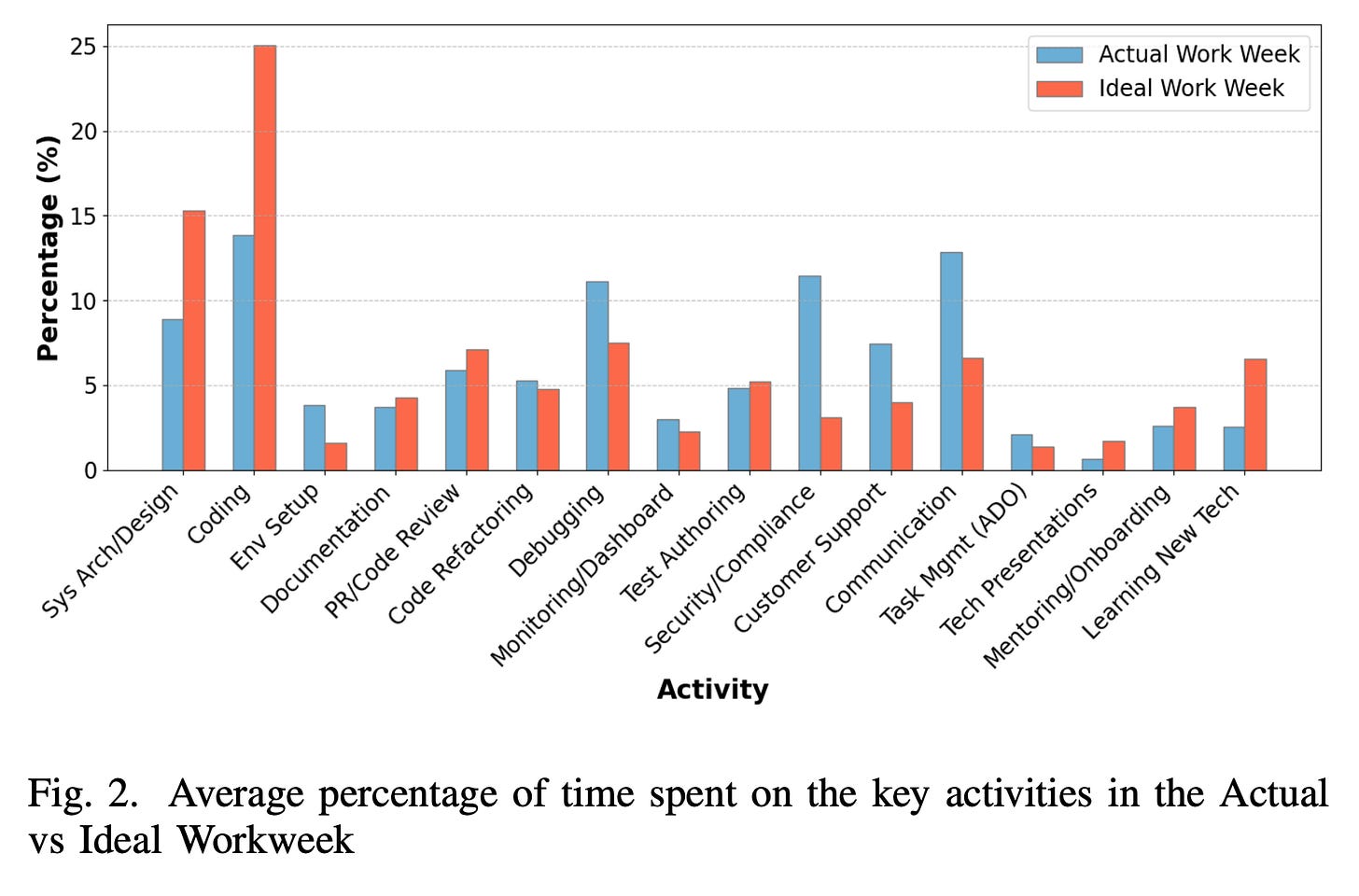

First, 26% is a task-level figure. In a Microsoft study, developers spend only about 11-32% of their time actually doing coding tasks—the rest is meetings, planning, debugging, code review, and all the other things that make software engineering a job and not just typing. As I—and many others—have pointed out, soft skills are extraordinarily underrated in the best engineers. Multiply straight through and you get a 3-8% project-level gain from coding alone. That number bumps up somewhat once you account for AI helping with adjacent work—debugging, code review, documentation—and comes back down a bit when you factor in the overhead of reviewing and fixing AI-generated code (which, as we’ll see, is not trivial).

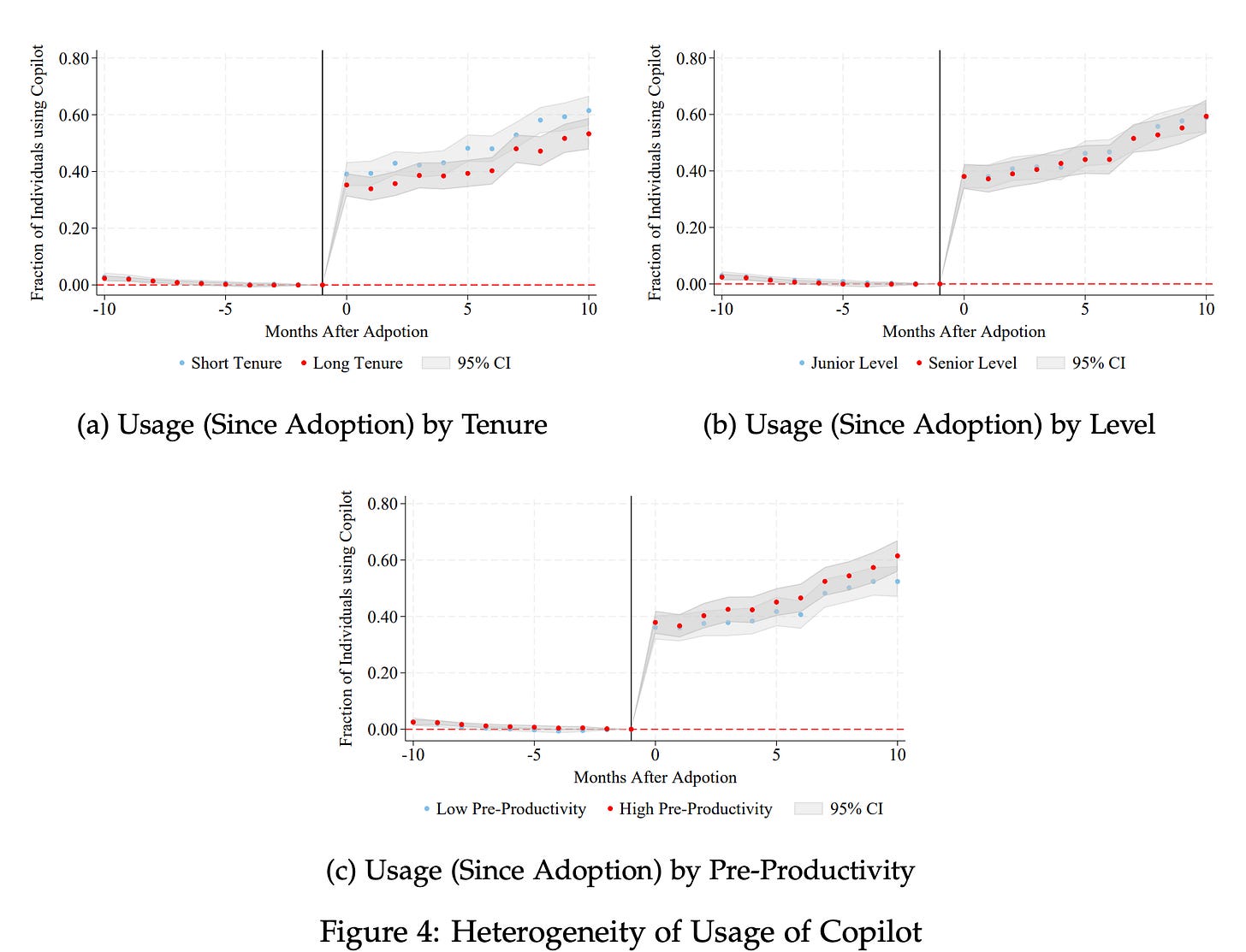

Second, adoption isn’t universal. Even with the tool freely available, only about 60% of developers were actively using it after a year (from MIT study, again). Newer hires adopted faster; some veterans stuck with their existing workflows.

Finally—and this is the one AI boosters don’t like to talk about—quality is a real concern. Studies show 40-62% of AI-generated code contains serious bugs. Refactoring (editing code for clarity/cleanliness versus functionality) is declining from 25% of code changes in 2021 to under 10% in 2024. Code cloning is up 48%. There’s a real technical debt story building underneath the speed gains. From my own testing, even the frontier models with the most profligate thinking settings still do dumb stuff all the time. I promise you—AI is not “one-shotting” complicated software engineering tasks without human supervision. Preferably, highly experienced human supervision. As I’ve said before, AI’s biggest benefits accrue to the most skilled/expert already.

Ok, so that’s a lot of stuff that can’t just be straightforwardly multiplied. But let’s do this.

20-26% task-level improvement. Let’s flatten between 11-32% spending on coding tasks to 20%. So, a modest 4-5% improvement.

However, debugging, code review, and documentation are tasks that take up a lot of time in the MIT study—it’s another 20%’ish of total time. AI definitely helps with all of this. So, let’s add on another 4-5% for this set of tasks.

After applying all these discounts—adoption rates, time allocation, overhead for debugging and review, quality adjustments—a defensible estimate for net project-level productivity improvement is roughly 10%.

Some, including me, thinks this is likely ridiculously low. The MIT study was in February 2025. Recent, but given how fast AI coding tools are improving, that was an eternity ago. It was also using Copilot—which no one cites as the leading coding tool/agent. That would be Claude Code.

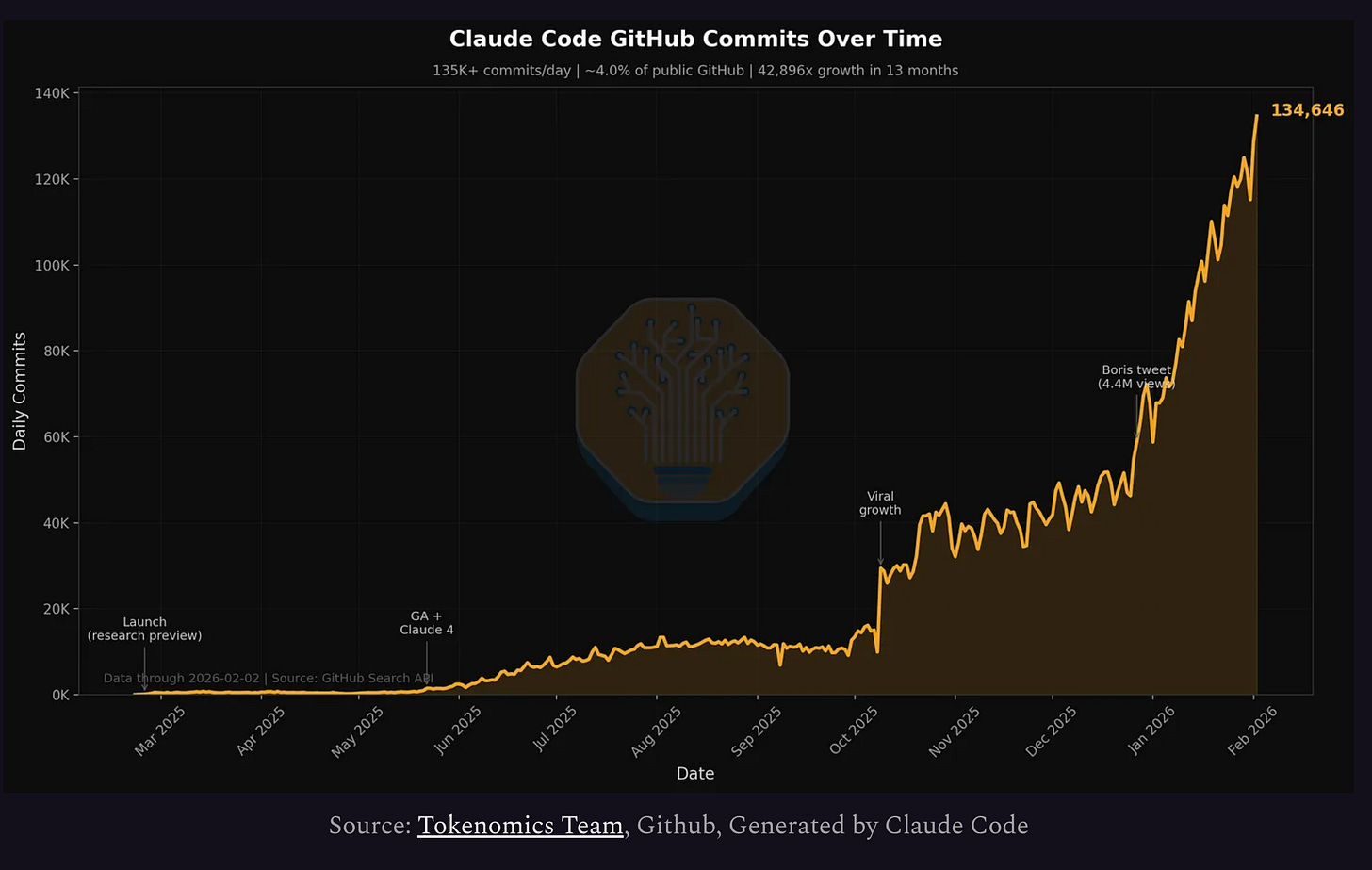

Additionally, the number of developers since April 2025 (Microsoft’s study) utilizing Claude Code and similar tools has skyrocketed—see the below chart from SemiAnalysis. But whatever, this is meant to handle a skeptic’s argument.

Now, with this likely way-too-low number, let’s do the math.

There are about 1.7 million software developers in the US (2.1 million if you include adjacent roles like QA and data scientists). Per BLS, total compensation is roughly $357 billion annually—about 1.2% of GDP. And critically, 58% of these developers don’t work in “tech”—they’re embedded in finance, healthcare, manufacturing, government. So this isn’t a Silicon Valley story. It’s an everywhere story.

Apply the 10% productivity gain and that gets us around $36B in additional output—which is, as a share of GDP, 0.12% annually.

Is that a big deal? Well, that depends on whose estimate you’re comparing this to.

Daron Acemoglu—a leading AI skeptic in economics—estimates that AI will contribute only about 0.05% to GDP growth per year. Our floor estimate, from one application of AI (software coding), already exceeds his total economy-wide number.

Meanwhile, Goldman Sachs forecasts AI will add 1.5 percentage points to annual productivity growth by 2027. Our software-only number is about 10% of that—from one use case and likely already a radical underestimate due to utilizing numbers earlier in the growth curve. The remaining 90% would need to come from AI applications in other domains.

The market, for its part, is pricing something close to the Goldman consensus plus an upside buffer. The S&P 500’s forward P/E is 22.2x (18% above the ten-year average) and the CAPE ratio is sitting at 40—90% of the 2000 dot-com peak. The equity risk premium is essentially zero. Stocks are priced for things going perfectly right.

So, how does that all net out? Well, even if AI delivers everything I’ve described in software, that alone doesn’t justify current market valuations. The 1990s DotCom Boom did produce real productivity gains, and the S&P 500 still fell 49% from 2000 to 2002 because expectations had run ahead of reality. The productivity was real. The prices were also wrong.

But, that should be no surprise to my readers here.

All this is to say: the productivity gains are real, they’re measurable, they exceed what the harshest skeptics predict, and they’re a meaningful economic contribution. But they’re also more modest than headlines suggest, subject to real quality concerns, and insufficient by themselves to justify the market’s AI euphoria. But it’s still a big deal in real economic terms.

And remember, I suspect that estimate is already too low and we shouldn’t be surprised if the developer uptake ends up higher and the productivity gains end up higher—easily doubling or quadrupling (from 2X in both multipliers) our figure, which would get us to about half of Goldman’s estimate just from improvements to existing software engineering and no new applications. Speculative? Sure. But I think most who are trying out these tools would easily take the bet on that figure over our conservative one.

What Actually Changes: Mechanical Skills

OK, so AI makes software developers more productive. That’s happening now and will continue. But the more interesting question—and the one that connects back to all the fear and excitement at the top of this piece—is what it means for skills and work more broadly.

I have a thesis here, and it’s one that I think most people aren’t going to love, because it doesn’t fit neatly into either the “we’re all screwed” or the “nothing’s happening” box.

Mechanical skills become less valuable over time. They always have.

The thing Anthropic’s Daniela Amodei said recently about humanities becoming more important is getting attention for good reason. She noted that AI models are already “very good at STEM,” and that understanding ourselves, understanding history, and understanding what makes us tick “will always be really, really important.” When Anthropic hires, she said, they look for people who are “great communicators, who have excellent EQ and people skills, who are kind and compassionate and curious.”

She’s right, and the broader trend she’s pointing at is real. But I want to push on this a bit, because I think the framing of “humanities vs. STEM” misses the deeper pattern.

Soft skills—communication, empathy, judgment, taste, the ability to understand what someone actually needs versus what they say they need—these have always been underrated and far more important in technical fields than most people appreciated. I’ve said that a few times already. I’ve worked in enough technical environments to know: the engineer who can explain what they’re building and why it matters is worth five engineers who can only build. The PM who can figure out the right thing to build is worth ten PMs who can manage a Gantt chart. Building the right thing has always been more valuable than building a thing. AI just makes that gap more visible because the “building a thing” part is getting cheaper.

But is STEM really going to go extinct? Do you, dear reader, really believe that? Does that make sense with experienced developers (and other experts) becoming massively more productive?

What’s happening is something more specific and historically familiar: the mechanical component of technical skills is being devalued, while the judgment component is being elevated. And this has happened before. Multiple times. We just have very short memories.

Historical Analogies

Photography

I discussed this in my book, but before photography, if you wanted a realistic visual record of something—say, a person’s face, a landscape, a historical event—you needed someone who could draw or paint with photorealistic skill. That was a rare, valuable, hard-won mechanical ability. It took years of training. Masters commanded premium prices.

Photography made that specific skill dramatically less valuable almost overnight. Now, it wasn’t worthless. In fact, there are still photorealistic painters today, and they’re impressive. However, the economic premium for “can render a realistic image” collapsed. What didn’t collapse was the value of composition, of artistic vision, of knowing what to point the camera at and why. The judgment survived. The mechanical skill didn’t.

Did photography destroy art? Obviously not. It transformed it. It freed artists to explore impressionism, abstraction, and a hundred other directions that weren’t about pure reproduction. The total economic and cultural value of visual art increased after photography. But the specific skill of “realistic rendering by hand” became a niche rather than a necessity.

I’ll also add on here: would you call the “real artist” of various photographs the camera? Should we credit Kodak, Canon, or Fuji instead of Ansel Adams or Annie Leibovitz? Even if we’re using a tool that makes certain mechanical skills less valuable, the artist is still the intent and motive driver behind it.

Typewriters

Just to belabor the point, for centuries, penmanship was a critical professional skill. In law, medicine, commerce, and government, the ability to produce clean, readable script was a prerequisite for professional work. People trained for years. Schools taught it as an important part of the curriculum.

The typewriter (and later, the computer) destroyed that. Not “writing”—the ability to compose clear, persuasive, well-organized prose is more valuable than ever. But penmanship? Nobody’s getting hired for their handwriting anymore. The mechanical skill evaporated. But, obviously, writers still exist.

Luddites (the real ones)

And then there’s the one everyone brings up, usually incorrectly (again, just to self-plug again, in my book!). The Luddites weren’t anti-technology. They were skilled manual weavers whose specific mechanical expertise (ironically, also a fruit of technological advancement) was being made obsolete by power looms. Their hard-earned mechanical skills became less important—allowing untrained workers (including women and literal children... for better or worse for the latter) “invade” and “devalue” the work. The result? Clothing became dramatically cheaper, demand exploded, and suddenly people were able to wear more than one single threadbare outfit.

Total employment in textiles increased after mechanization. But the specific job of “skilled hand weaver” largely disappeared.

The Luddites’ mechanical skills became less valuable. The industry their skills served became more valuable. Both things were true simultaneously, so it isn’t really as simple as “technology arrived, jobs gone.”

You see where this is going. In every case, a mechanical skill that was previously the bottleneck gets automated or dramatically cheapened. The people who built their careers on that specific mechanical ability face real disruption. But the broader field doesn’t die—it grows. And the skills that survive and appreciate in value are the ones that involve judgment: knowing what to build, what to paint, what to write, what to weave. The “what” and the “why” survive. The “how”—at least the mechanical “how”—gets commoditized.

AI is doing this to coding right now. The mechanical act of translating a well-understood requirement into working code is getting cheaper fast. Junior developers who could write clean boilerplate were gaining 27-39% in the MIT studies—precisely because boilerplate is the most “mechanical” part of programming. Senior developers gained only 8-13%, because their work involves more judgment, architecture, and navigating ambiguity—things AI is worse at.

This doesn’t mean software engineers are doomed. (I’ve written about this before.) It means the mix of what makes a software engineer valuable is shifting. Writing code is becoming less of the value. Understanding what code to write—and whether code is even the right solution—is becoming more of it.

And yes, this pattern will extend beyond software. Any domain where AI can reliably perform the mechanical components of the work will see the same shift: mechanical skills devalued, judgment skills elevated. The domains themselves won’t die. They’ll grow, because productivity increases expand the total pie. But the specific humans who refuse to adapt their skill mix will face the same disruption the Luddites did.

So Now What?

Here’s the thing that frustrates me about the current discourse: everyone’s arguing about the magnitude without agreeing on the mechanism. And the mechanism is actually pretty clear if you look at the history. The productivity gains from AI in software are real—not catastrophic for software engineers, especially at the senior level. AI will expand to other domains over time, unevenly. Mechanical skills will be devalued; judgment skills will be elevated. The economy will adjust, imperfectly and with real human costs.

The future Norbauer talked about so evocatively: a Star Trek future, where it’s all going to be amazing—yeah, it’s probably hard to imagine it’s right around the corner. But we aren’t looking at some kind of dystopia either.

Unfortunately, what is likely isn’t as clickbait-friendly. Tools will get better, mechanical bottlenecks fall away, and the people who can exercise judgment about what to build and why become more valuable than ever. That’s not a dystopia. It’s not a utopia either. It’s not a white-collar apocalypse. It’s also not a nothingburger—far from it.

It’s just... the next version of a pattern we’ve seen play out for centuries. Maybe we’ll get to AGI eventually but, in the meantime, AI is going to be an important tool—which, lest you forget, the computer also was, with all of the impacts it ultimately had.

Thanks for reading!

I hope you enjoyed this article. If you’d like a serious yet accessible guide to AI, I published a book titled What You Need to Know About AI, now available as an audiobook narrated by me!

You can learn more and order it on Amazon, Audible, Barnes and Noble, or select indie bookstores in the Bay Area and beyond.

I appreciate the thoughtful analysis. My concern is that it assumes AI will progress along a historical average trend line. I’m not convinced that’s the right model.

AI feels more like it’s on an intelligence J-curve. For a long time, progress looks incremental, even overhyped relative to impact. Then capability compounds. Once systems begin meaningfully improving reasoning, autonomy, and self-directed learning, historical averages stop being useful predictors. They understate what happens when feedback loops kick in.

Leaders like Sam Altman and Demis Hassabis have publicly projected timelines for AGI in the 2028–2030 range. They could be wrong. But if they’re even directionally correct, we’re not talking about marginal productivity gains—we’re talking about a structural shift in how cognitive labor is performed.

And that’s the key point: once (and if) we reach AGI, I don’t think “decision-based” knowledge work remains protected territory. Strategy, analysis, forecasting, optimization—these are ultimately reasoning tasks. If general reasoning becomes automatable at scale, the boundary between “assistive AI” and “replacement AI” blurs quickly.

History is useful—but if we’re entering a regime change, historical averages may dramatically understate what’s coming.

It's always nice to read an intelligent article with a reasonable perspective in the forest of propaganda by AI companies and their investors. You never disappoint, James.

In a non-professional space, I had an experience yesterday that gave me pause. Given that Google Chrome automatically gives AI responses, using AI is unavoidable. So yesterday as I was planning our retirement budget, I asked Chrome a question about taxing social security benefits. I'd read that up to 85% are taxable if you make more than $44,000. As part of my exploration, I prompted that if our only retirement income were from social security benefits and gave it a specific amount, how much tax we would pay annually. It responded with an amount about half of what I had mentally guessed and listed the calculation. It made sense and I could see what information I didn't know so I was about to accept it. But for some reason, I clicked on the "learn more with AI" button.

It transferred my prompt to Gemini, which came up with a different calculation and answer, saying that I would owe no taxes. It told me where my misunderstanding was. I then asked Gemini several questions from the previous Google Chrome formula, such as "what about...?" Each time, it changed it's answer and calculation, increasing the amount of tax I would pay. Perplexed, I searched through the links below it in order. The ones at the top were from investment advisor companies trying to get your business and one was from H&R Block. It was evident that none of the authors understood the real formula and all of the articles were incomplete and confusing.

The last link was to irs.gov. After reading several articles and still being confused (because they "dummy down" the information by making it incomplete), I finally found a tool on their website that you can use to calculate your exact amount of taxable income and resulting tax. It confirmed that no tax would be owed.

But that left any faith I had in AI as a search tool obliterated. Whatever it says, sounds logical. But that is very misleading. Over the last year, I've used all of the LLMs on topics where I'm an expert and found the results consistently wrong. My conclusion is that AI is measured on benchmark tests that it is trained against. But in the real world, the results are much worse than what the propaganda by the AI companies and those invested in them would have us believe, even on simple data with simple formulas. That's why those using AI advise that you have to keep prompting to finally get the result you want. But often, the results get worse, not better.